Special Theme

An Approach of the Info-Forum Museum

Decolonizing Museum Catalogs: Defining and Exploring the Problem

Discussion

Not only the product (the detailed catalog itself) but the process of producing collaborative catalogs and related publications, workshops, and seminars brings museum collections out of storage and into multiple modes of discussion and display. These can lead to new knowledge for both museums and source community members and lead to revitalization of art forms and technologies.

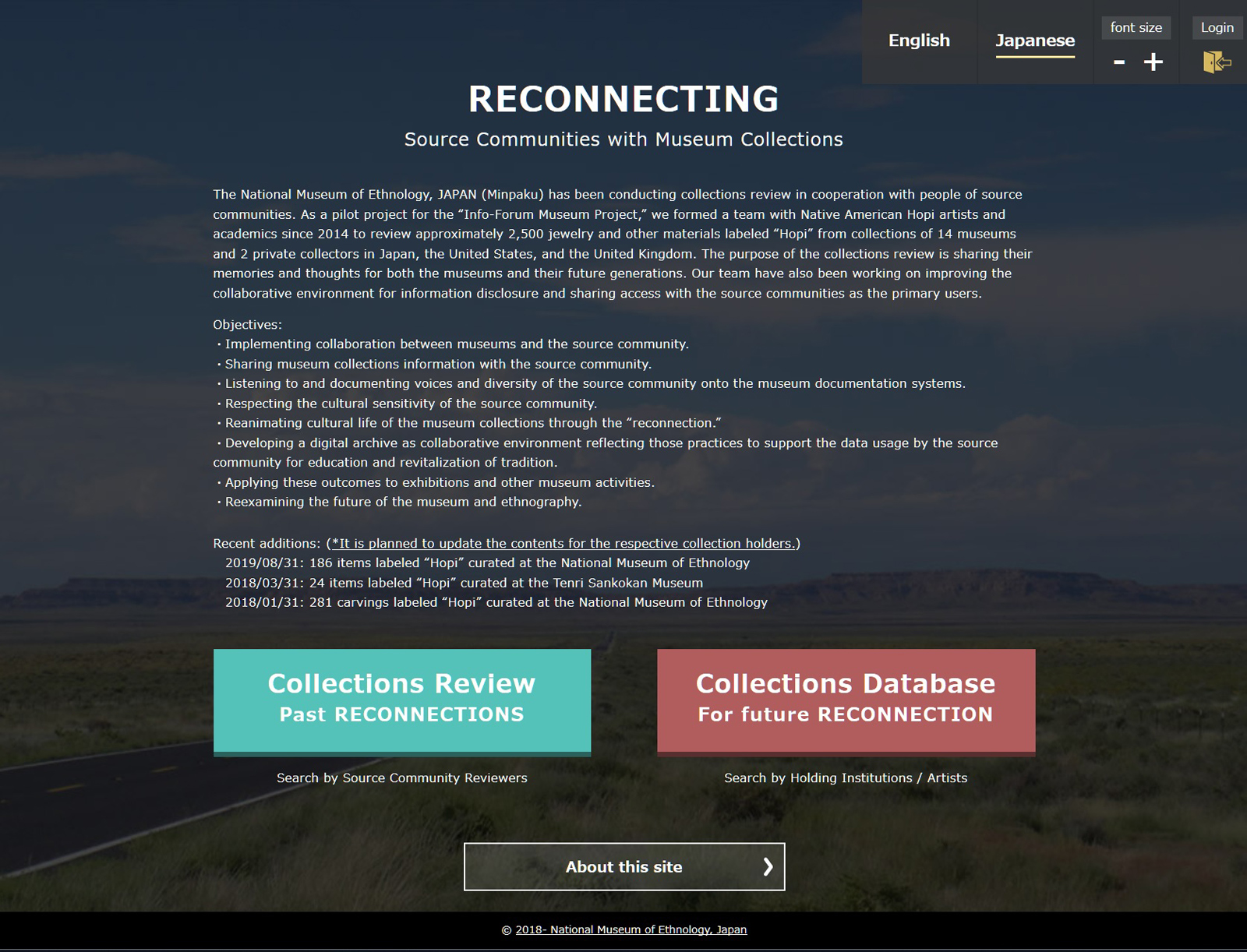

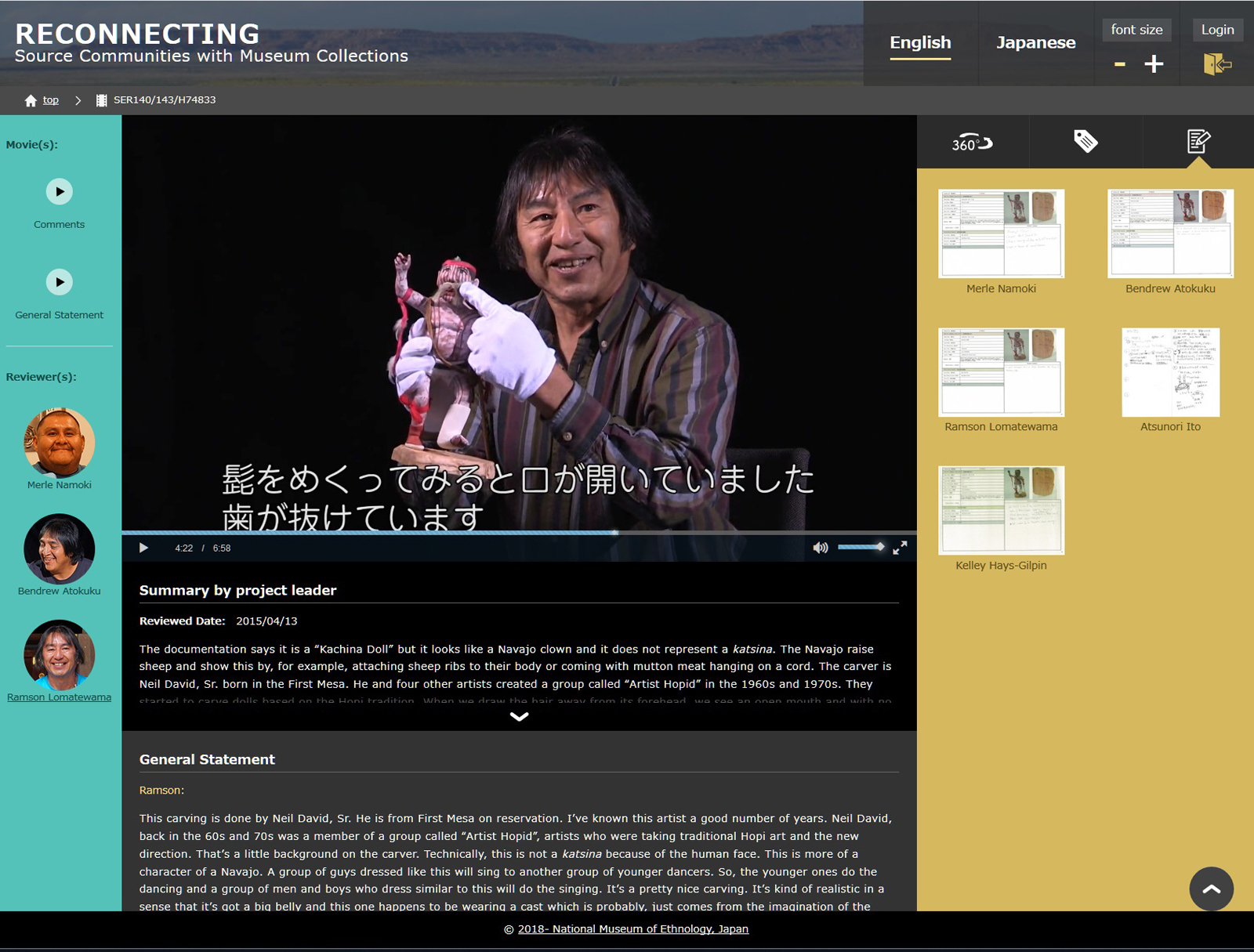

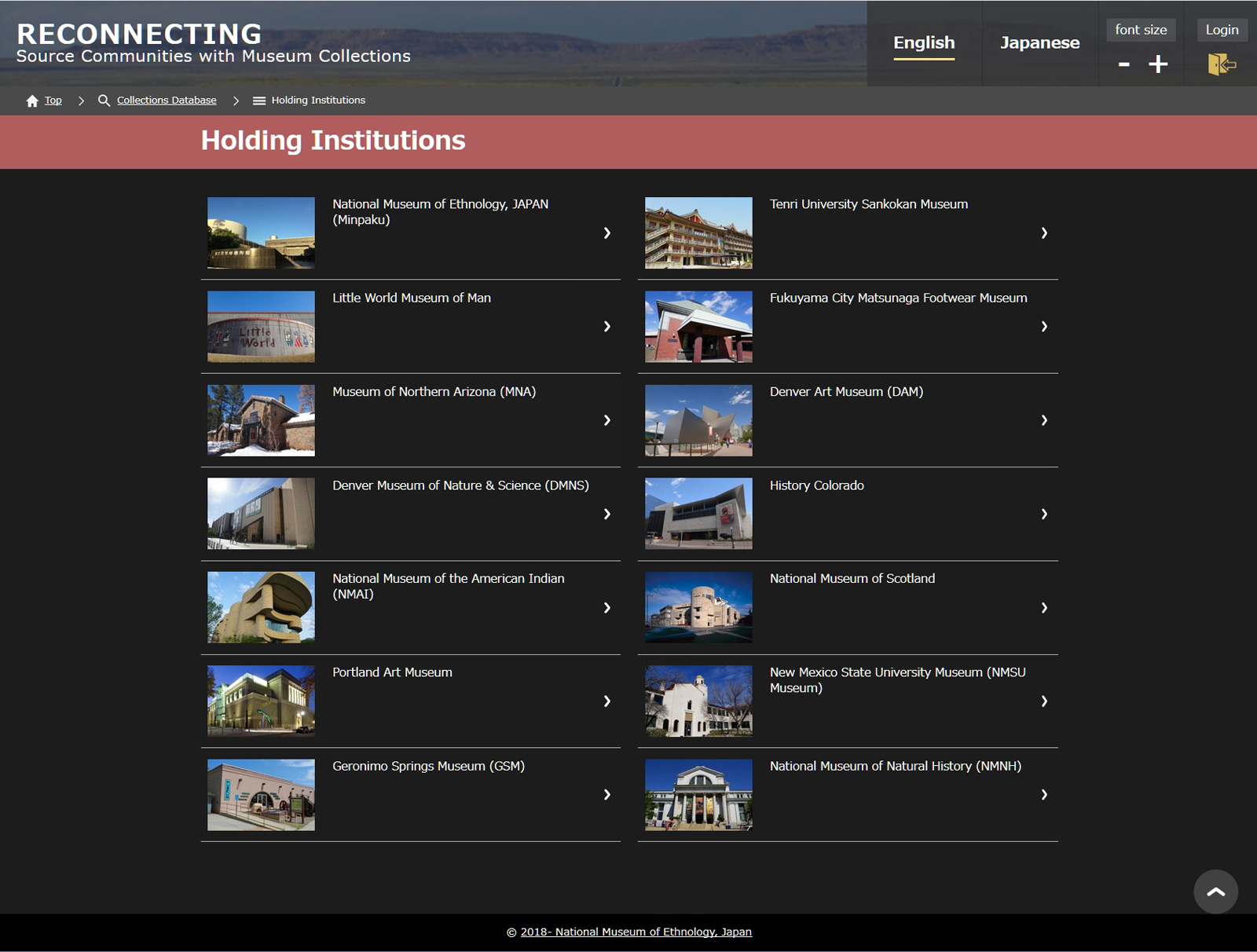

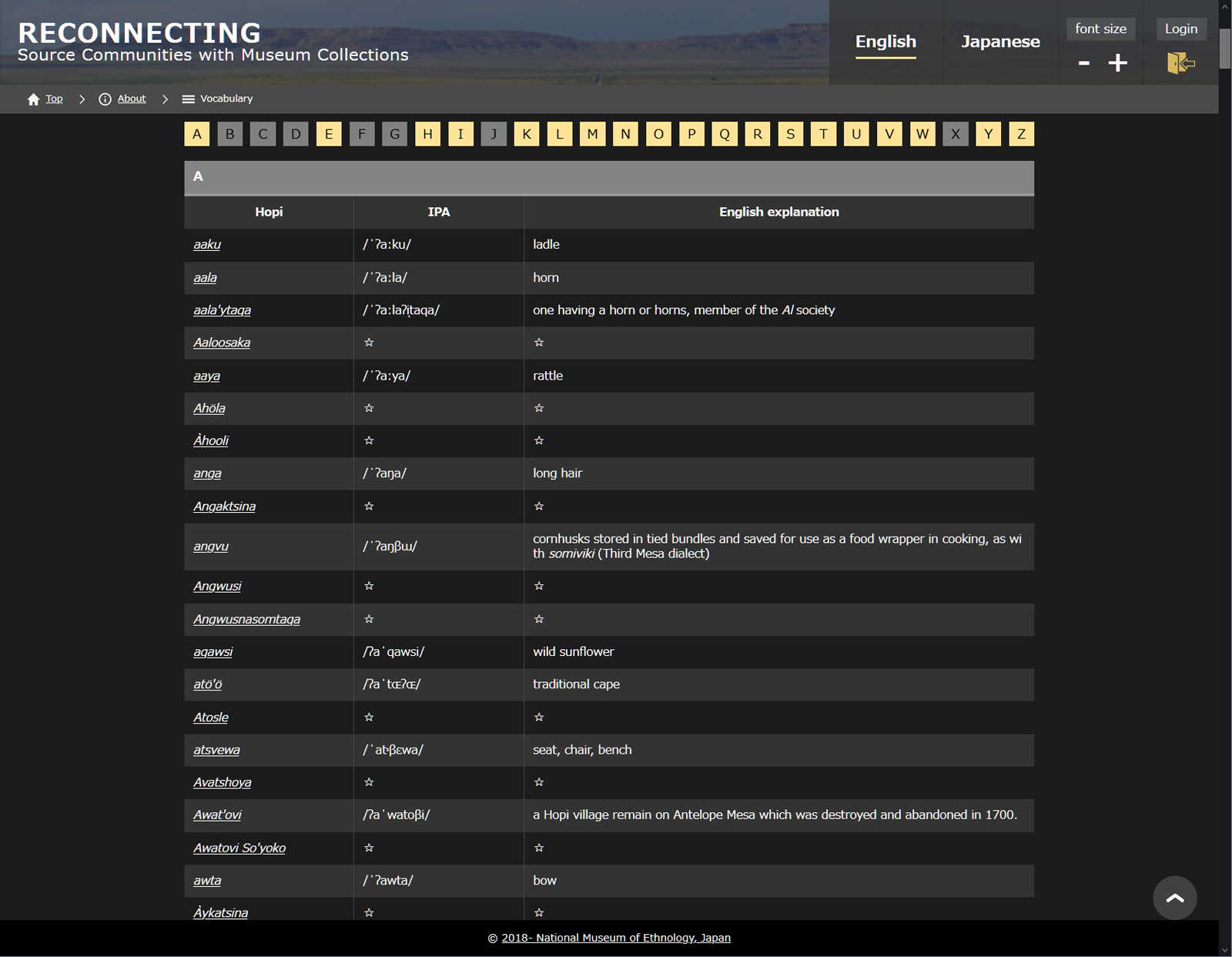

Museum ethnographers and archaeologists should pursue the goal of making objects and data available to descendant (source) communities. In some cases, the mode of delivery could be the same as simply making images and records available to all, but we should when possible reach out directly to community cultural centers, government officials such as tribal council members, schools and teachers, and artists’ guilds. Let them know where to find the information and what else the museum could do that would interest them. To be effective, mode of delivery must vary depending on community and museum resources, and on how the community wishes to use the information. Consider delivery to community museums, archives, and schools by digital media or even printed material in binders if online access is difficult for community members. Consider mobile-friendly interfaces – more young people in rural communities have smart phones than access to full-sized computers that are reliably connected to the internet. Consider source community user-friendly functions like key word search, local language index, visual narrative selection told by their relatives, friends, and neighbors, and easy-to-understand guides to key words and definitions. It is not necessary for a collection review transcript to just be a museum collection reference database. It could be a tool to document and understand a complex, diverse, and changing body of knowledge about the source community through their views of individual objects held in the museums. We focus on what is important to the community members. It is a robust record of their own personal connections, to be handed down to their descendants (Figure 20-27).

Figure 20. Top page of the digital archive; “Reconnecting Source Communities with Museum Collections” (https://ifm.minpaku.ac.jp/hopi/)

Figure 21. The page for researching the past Reconnections (collections reviews). Here, users can select a combination of reviewers and holding museums (https://ifm.minpaku.ac.jp/hopi/review.html)

Figure 22. Reviewer’s comment on the item (https://ifm.minpaku.ac.jp/hopi/reviewDetail.html#id=143)

Figure 23. The list of holding institutions (https://ifm.minpaku.ac.jp/hopi/holdingInstitution.html)

Figure 24. Index of the Hopi words mentioned in the past collections reviews (https://ifm.minpaku.ac.jp/hopi/vocabulary.html)

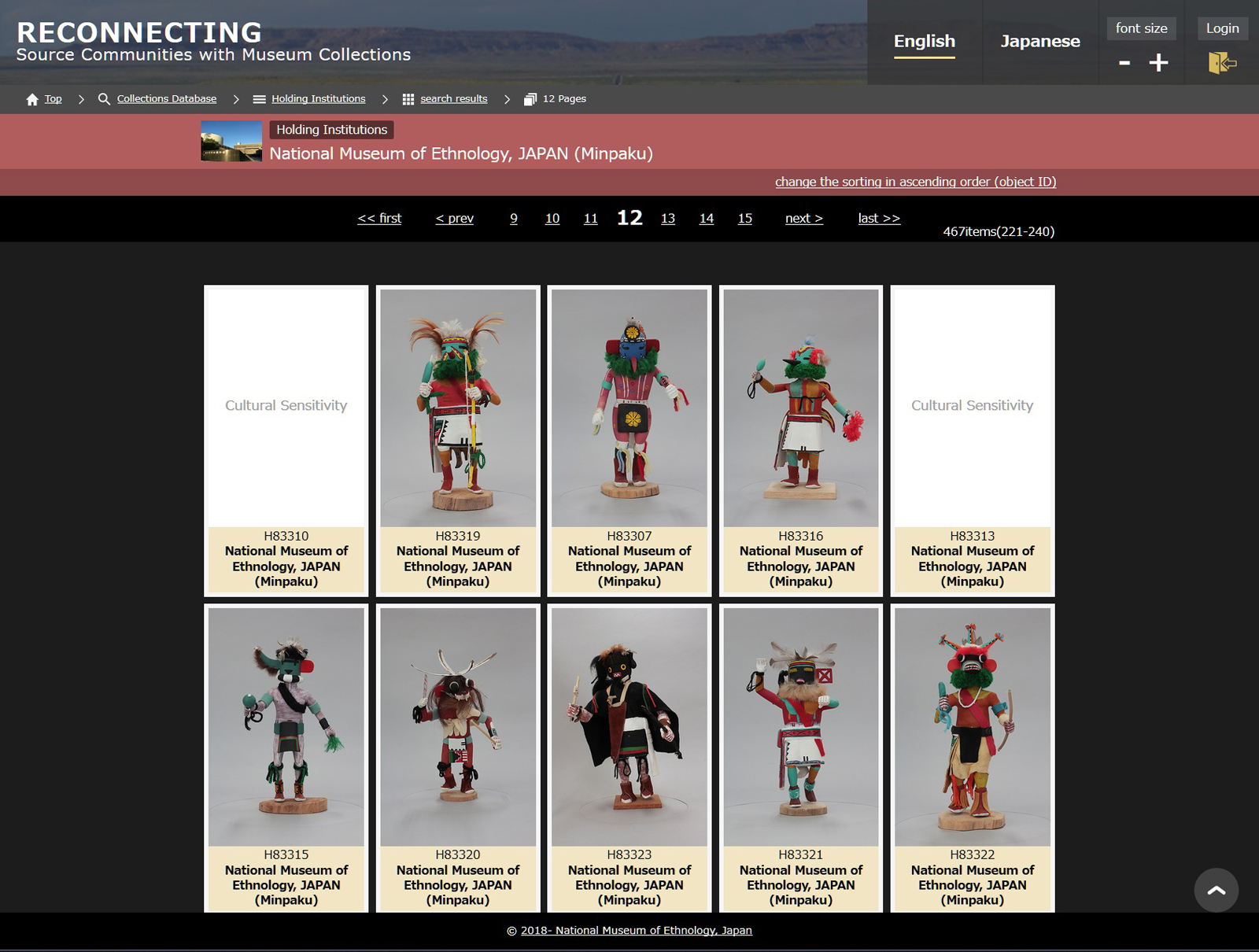

Figure 25. The list of items (https://ifm.minpaku.ac.jp/hopi/searchResult.html#holdingInstitutionCode=1&page=12)

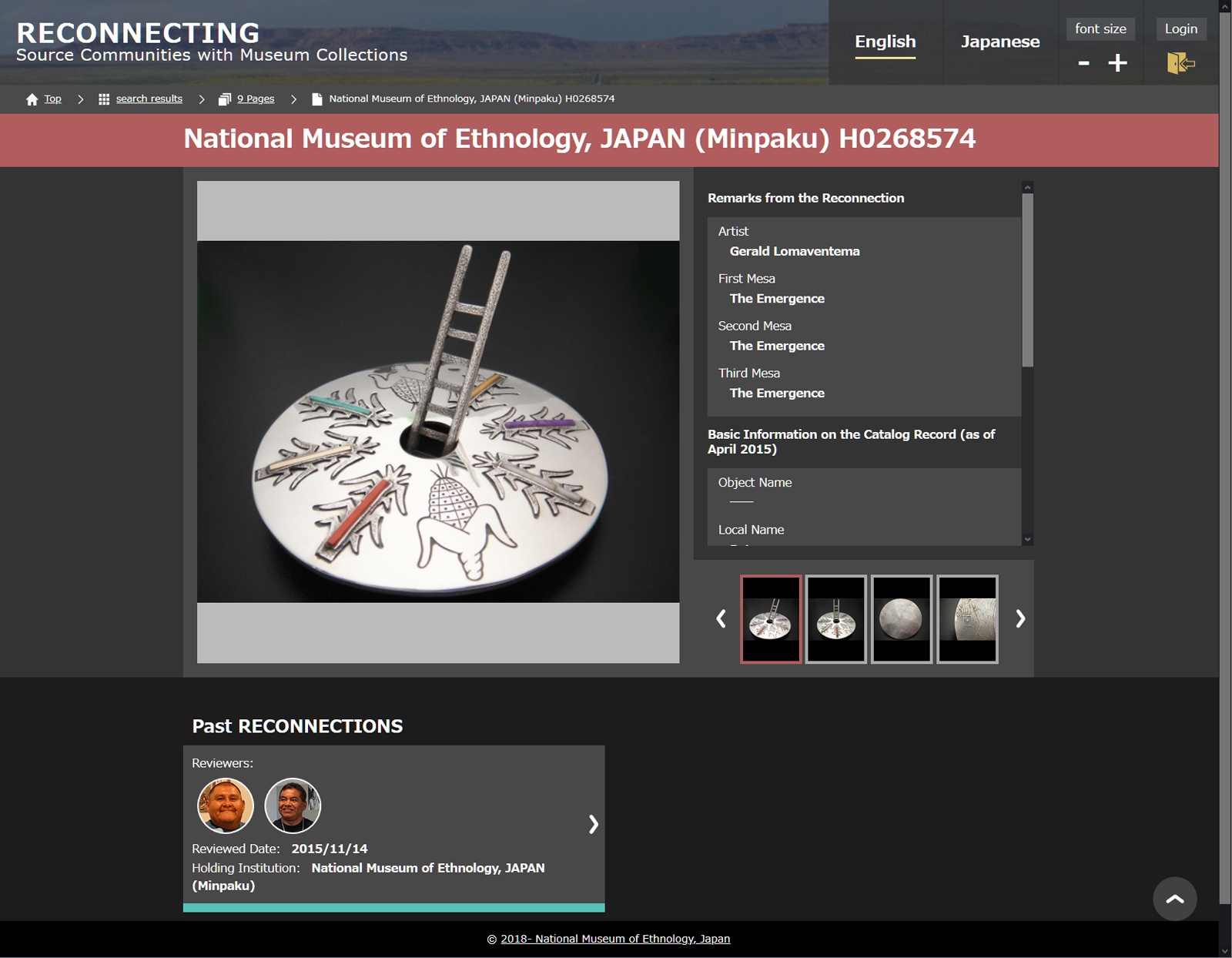

Figure 26. Users can go directly to the page of the past collection review from the object reference page (https://ifm.minpaku.ac.jp/hopi/objectDetail.html#id=H0268574)

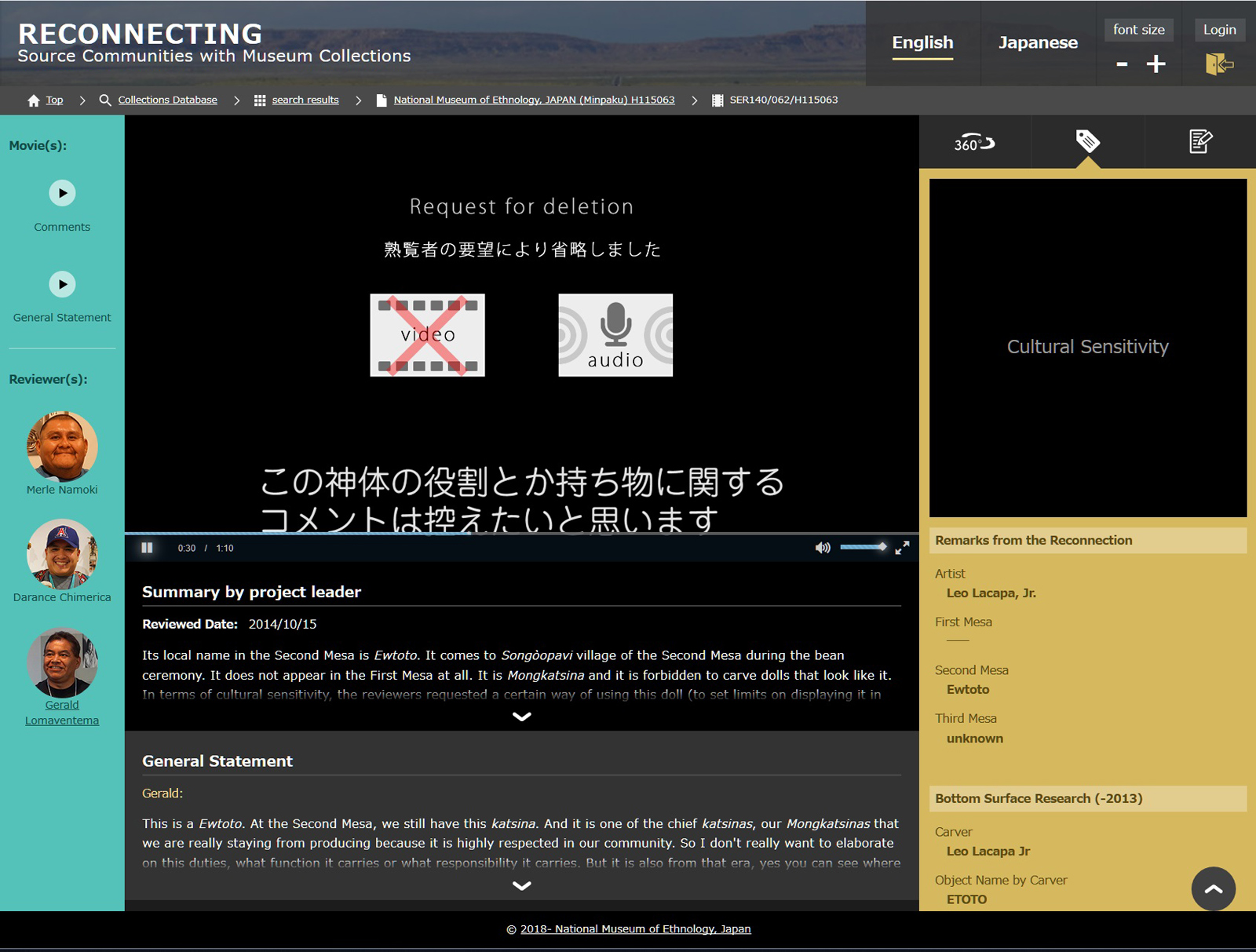

Figure 27. Some parts of review comments have been deleted at the request of the reviewers (https://ifm.minpaku.ac.jp/hopi/reviewDetail.html#id=62)

Few source community members will need or even want to see all our data. Images of thousands of pottery vessels – or worse, potsherds – are only interesting to a small segment of the professional community. Up front consultation with the community about which artifacts, photos, or sound recordings are likely to be of interest will save a lot of work and produce more useful results.

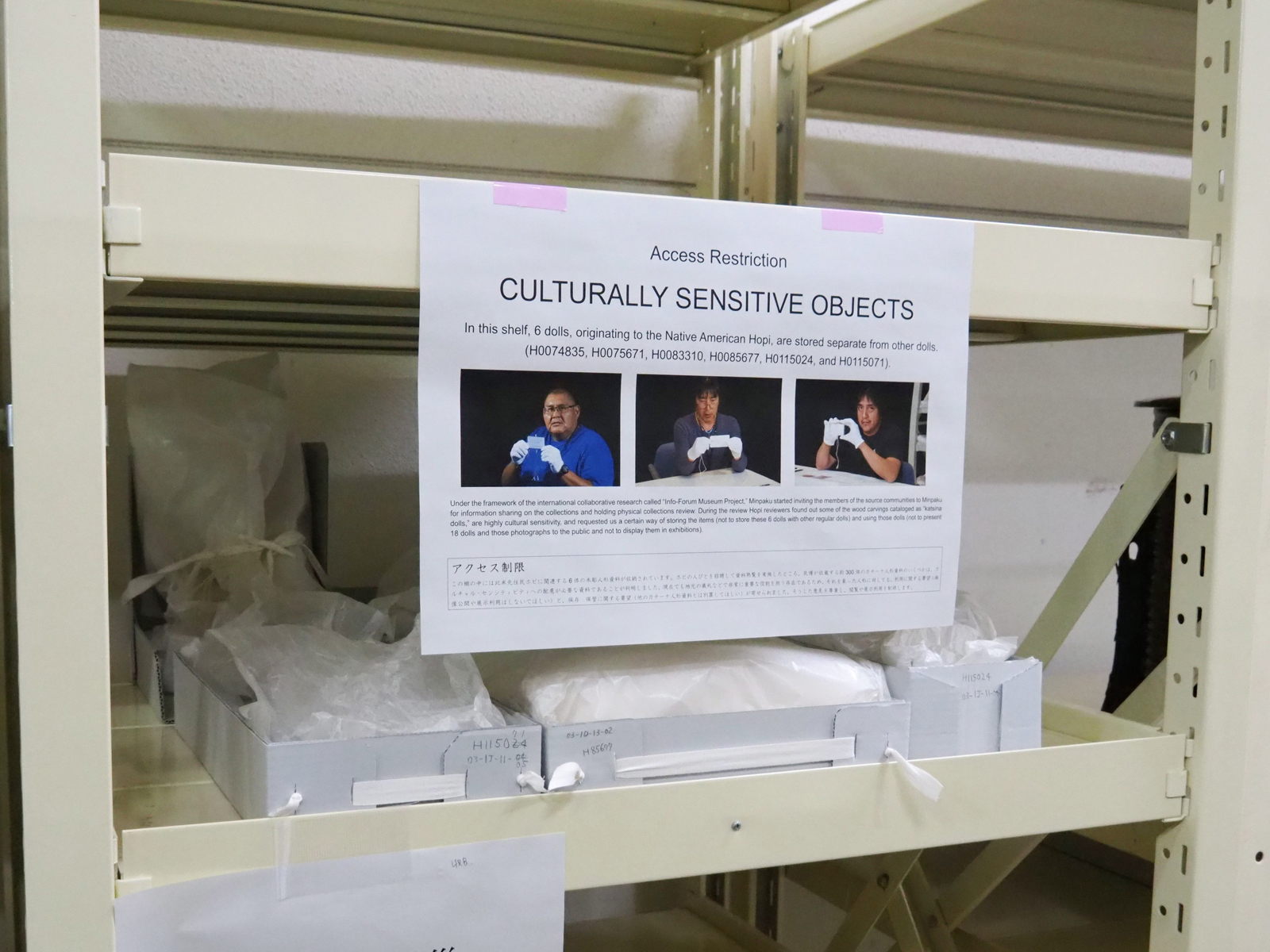

Community sensibilities about what is appropriate to view differ. In the United States and Canada, for example, indigenous people usually prefer not to view images of human bones or funerary objects; for many these are taboo subjects and engaging with funerary artifacts can be a real threat to health and well-being. In Mexico, there is no such taboo; human bones are displayed in churches and depicted in artworks. Not only do preferences and prohibitions vary in different countries on one continent, but opinions vary within communities. In the Zuni Amidolanne catalog project, some community members thought that pottery vessels from archaeological sites they consider ancestral should be shared so that the world will understand the great artistry of Zuni ancestors. Others thought images should be available only to community members. Some feared that artists from other tribes would copy their designs; others felt that all archaeological materials were sacred and should not be exposed to outsides (Film 10) (Figure 28).

Film 10. Hopi reviewer Merle Namoki holds a label tied to the object and requests that the holding museum should not display this item and/or its digital image online for the general public (“H0075677” of Minpaku) (Ito 2018a)

*Click here for Transcription

Figure 28. Access Restriction; separate placement some cultural sensitivity objects put in case from other objects in Minpaku storage. (April 18, 2019, photo by Atsunori Ito)

In-person visits by community cultural experts to collections can be important for accurate identifications as well as promoting true connections between people and things. But visits can be expensive for busy artists and anybody with commitments at home and work. How flexible can we be? Can a curator or collections manager bring objects to a community museum or cultural center for examination? AAMHC at Zuni borrowed archaeological objects from the National Museum of the American Indian to display locally. These pottery vessels and tools were excavated from an ancestral Zuni village in the 1920s. Thousands of objects from the village of Hawikku were stored in Washington, D.C. and most Zunis did not know they were there until the community museum negotiated the loan. Now Zuni potters can visit the pottery for in-person study (Figure 29). Some potters, such as Timothy Edaakie, are using these ancient designs as inspiration in new works.

Figure 29. Long-term loan items on display at AAMHC (June 3, 2012, photo by Atsunori Ito)

Jim Enote’s Museum Collaboration Manifesto on the Zuni museum’s website sets the stage. Enote leads the collaborative catalogs movement, which is more than a series of projects: “Inclusion of expert peoples representing the source of collection materials is the keystone of a collaborative movement” (Enote 2015).

What we have learned: we can build relationships with source communities that our institutions didn’t cultivate when they were founded, it isn’t too late to start, and collaborations can be sparked in many ways. Community museums like the AAMHC might reach out to larger, historic, colonial-era institutions like MNA. Large national museums like Minpaku might devote resources to initiating a wide collaboration. Small and even temporary institutions like artist markets might evolve into more substantive long-term collaborations. An important early step is that our established institutions must give up our own sense of professional superiority, and truly listen to what members of source communities want to accomplish and how (Film 11).

Film 11. Ramson Lomatewama gives his remarks on the “Reconnecting Project.” (Ito 2018b)

*Click here for Transcription

The purpose of the workshops hosted by Minpaku (Appendix 1), and of this special theme, is to assert and promote the idea that ethnographic collections must be grounded in a rich body of data from the source community and reflect scientific perspective, worldview, language, and attitude toward objects. For example, to many indigenous communities, everything is alive, and everything has a purpose and an intended life cycle (Hays-Gilpin and Lomatewama 2013).

In summary, these ethnographic projects show that collaborative catalog projects are time-consuming and challenging, but they have a great deal of potential to share accurate identifications, and cultural and historical contexts, with source community members as well as museum audiences and our fellow investigators. Untold challenges remain – technological, cultural, and budgetary. But each journey starts with a single step, each catalog starts with a single entry, and each collaboration starts with a conversation.