Creatively Utilising the Encyclopaedia Cinematographica Film Project: Visual Repatriation of the Masakin

Table of Contents

- Ⅰ. Introduction

- II. The EC Film and the Masakin

- III. Curating the EC Films in Japan

- IV. Visual Repatriation of the Nuba

- V. Conclusion

Abstract

This article explores how archive material, such as the Encyclopaedia Cinematographica (EC) Film Project, can be re-evaluated and utilised by both the film subjects and the Japanese public through visual repatriation. In this article, I explore how the digitalized films on the Masakin in Sudan can be utilised with support from Japanese curators, as they have the potential within a source community to evoke collective memories. While the outdated EC films have been extensively criticised, the debate over the Nuba people’s representation has largely not concerned them. The fragmentation and dispersal of many communities has instigated a feeling of cultural loss among the Nuba people, as they have adapted to modern, urban lifestyles. Under these social conditions, the visual repatriation project demonstrates that the Nuba people seem to search for their past identity in these archival films, which strengthens their sense of belonging to the Nuba community.

Ⅰ.Introduction

This article explores how archive material, such as the Encyclopaedia Cinematographica (EC) Film Project, can be re-evaluated and utilised by both the film subjects and the Japanese public through visual repatriation. Film archives influence cultural memorisation and potentially overwrite the past to not only reshape the present but also influence the future. Visual repatriation refers to ancestral images, historical knowledge, and museum artefacts being returned to source communities: that is, the societies where these materials originated (Peers and Brown 2003: 1). This process can be used as a focal point for interviews in which source community members share narratives about their culture and history (Peers and Brown 2003: 14).

Nannyoga-Tamusuza and Weintraub (2012), who implemented the Music of Uganda Repatriation Project, explain that the repatriation of visual and auditory ethnographic data does not simply entail returning what was recorded; rather, it is a process that raises many ethical and practical questions: What is the community of origin? How will people in these communities respond to fieldworkers’ efforts to return these visual images to the community? Furthermore, by watching a film of their past, viewers may develop a new understanding of their historical trajectories and present.

To demonstrate this, I conducted a project to return EC films to the displaced Nuba people. In the 1960s, thirteen films of the Masakin—an ethnolinguistic group that resides in Sudan’s Nuba Mountains—were filmed and produced. Japanese curators/anthropologists and I, an anthropologist of the two Sudans, co-managed a project to execute this visual repatriation. Even though the general EC film archive has been internationally preserved (including in Japan), there are few examples of its visual repatriation, which is partly because the original 16mm film makes it difficult to transport and screen in places without a display device, unless it is digitalised beforehand. Moreover, the distinct filmmaking styles of the EC as well as the objective, positivistic styles of every filmmaking procedure must be scientifically controlled and therefore remain obscure. This is partly because visual anthropologists caution that the images, whether photographic or film, are not pure objective records of the filmed reality. Although there was no formal ending, in 1995, the EC concluded its activities because of a severe lack of funding for the Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film (IWF) in Göttingen. Does this mean that there are no more opportunities for the practical utilisation of these materials? Is there no alternative but for outdated films to be preserved in storage?

In this article, I explore how films from the past can be utilised, as they have the potential within a source community to evoke collective memories. This approach to the EC films shifts the focus from the filmmaker’s style to how a source community views and derives meaning from them.

This article is composed of three sections: the EC film on the Masakin, the current use of the EC film by Japanese curators, and the visual repatriation of the digitalised film to the Nuba people.

II.The EC Film and the Masakin

The EC was founded in 1952 by Gotthard Wolf, director of the IWF, to collect, record, and preserve ‘scientific’ films. From the beginning, there were three categories in which films were to be collected: biology, ethnology, and technical science. The EC filmmakers produced over 3,000 films in over thirty years, and ethnological films were the most common. Wolf had a clear vision about the scientific films and emphasised their distinction from other documentaries. He claimed that scientific films should have several short film units that cover the actions and behaviours typical of an animal, culture, and material. In other words, he believed that every unit of a film must be a faithful record and reproduction of reality that has been divided into individual parts that compose the whole subject. Therefore, the filming procedures had to be ‘scientifically controlled’ as much as possible, which meant there was no staging, acting, or interference from the filmmaker in the activities being filmed. In post-production, strict editing was obeyed; therefore, there was no manipulation of the scenes by rearranging the chronology, for example, or by adding interrupting elements, such as commentary or music (Husmann 2007: 387–388).

The EC’s positivistic, objective method can be observed in sixteen films on the Masakin, a minority group that resides in the Nuba Mountains, which is located in the geographical centre of the formerly undivided Sudan. The films on the Masakin were made from 1962 to 1963 during the German Nansen Society’s anthropological expedition to Sudan (i.e. the Nansen expedition).1 The five-man team (including the author of these films, Horst Lutz) arrived at the Nuba Mountains in December 1962 and remained for two months in a Masakin settlement called Tadoro. Following the principles of the IWF’s anthropological filmmaking style, the team recorded agricultural practices, economic activities, dances, and musical performances of the Masakin: 1) women’s housework, cooking, and tattooing; 2) crop production processes, including harvesting, carrying, and threshing sorghum; 3) the performance of musical instruments made of clay or antelope horns; and 4) wrestling practices (Table 1). While the films are silent and recorded in 16mm format, three titles (E694: Herstellen eines Spiel-Schwirrholzes, E695: Formen einer Flöte aus Ton, and E701: Auftritt einer Sängergruppe mit Hornbläsern) also recorded sound. In each film there was detailed information on the scenes.

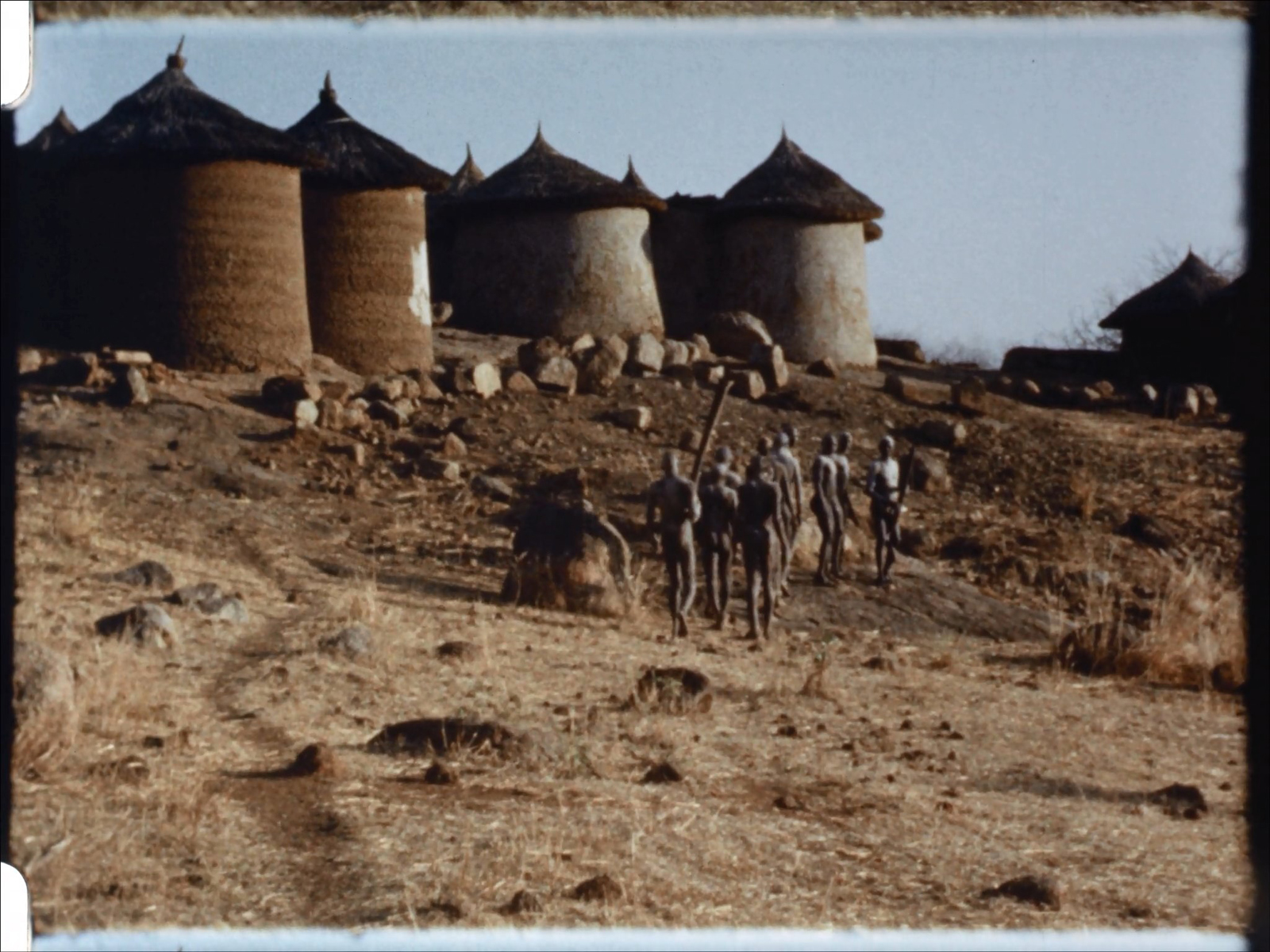

These collections reflect the cinematic style of filmmaking style that was typical of the EC, like the film Auftritt einer Sangergruppe mit Hornlblasern, for example, which presents a male chorus group. It involves two men carrying an extended horn, as they appear from the screen’s left, moving to the middle and stopping precisely in front of their houses. As they stop, they seem to be holding eye contact with the cameraman (Figure. 1). Then the camera captures their chorus, which responds to the solo singer at the beginning before being supplemented by two horns (an antelope horn and a clay horn). The men’s bodies are painted white with a material that is possibly sorghum flour or ash. Finally, the chorus group leaves the frame. The recording was well prepared, and the team made all possible efforts to avoid the filmmakers’ interferences with the subjects during shooting. Thus, the visual/sound recording was conducted in a well-controlled setting, from the scene composition to the camera’s position. Also, the existence of the filmmakers and directors is absent from the screen as much as possible.

| EC No. | Title (English Title) | Length of Film (min.) |

Shooting Year |

Release Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E 694 | Herstellen eines Spiel-Schwirrholzes (Making a Wooden Toy Bullroarer) | 8 1/2 | 1962 | 1964 |

| E 695 | Formen einer Flöte aus Ton (Making a Clay Flute) | 9 | 1962 | 1964 |

| E 696 | Herstellen von Schurzen aus Rindenstoff (Making Loincloths out of Bark) | 13 1/2 | 1962 | 1964 |

| E 697 | Wasserholen (Drawing of Water) | 4 | 1962 | 1964 |

| E 698 | Zubereiten und Essen einer Mahlzeit (Preparing and Eating a Meal) | 10 1/2 | 1963 | 1964 |

| E 699 | Ausschachten einer Grabkammer (Digging a Burial Chamber) | 6 | 1963 | 1964 |

| E 700 | Beibringen von Ziernarben (Scarification) | 21 | 1963 | 1964 |

| E 701 | Auftritt einer Sängergruppe mit Hornbläsern (Performance by a Group of Singers Accompanied by Two Horn-Players) | 5 1/2 | 1963 | 1964 |

| E 702 | Dreschen von Hirse für den Bedearf Während der Ernte (Threshing Millet for Consumption during the Harvest) | 9 1/2 | 1963 | 1964 |

| E 703 | Hirseernte (Millet Harvest) | 10 | 1963 | 1964 |

| E 704 | Hirshedrusch (Threshing Millet) | 12 1/2 | 1963 | 1964 |

| E 705 | Übungsringkämpfe (Wrestling Training) | 8 1/2 | 1963 | 1964 |

| E 1097 | Einkleiden eines Ringers (Dressing a Wrestler) | 6 | 1963 | 1967 |

Figure. 1 Still Image from Auftritt einer Sängergruppe mit Hornbläsern

III.Curating the EC Films in Japan

The full archive of the EC films has been established in Austria, the Netherlands, the United States, and Japan, while partial archives exist in other countries, including France, the UK, Portugal, Switzerland, Canada, and Turkey (Husmann 2007: 388, Fuchs 1988: 226). In the 1970s, the Simonaka Memorial Foundation in Japan purchased the full archive (biology, ethnology, and technical science) in order to open the materials to the public. The National Museum of Ethnology (also known as Minpaku) also has over 70,000 audio-visual materials, including 1,336mm of 16mm film on ethnology.

In Germany, however, the EC project gradually waned, which was partly due to its stoic, positivistic style of EC documentary filmmaking that was heavily centred around Western culture. Hence, it eventually became obsolete. After its last meeting in 1992, the EC editorial meeting was no longer held. Finally, the IWF closed in 2010 because of financial difficulties. Itsushi Kawase, a Japanese anthropologist (Kawase 2019: 159), interviewed Manfred Kruger, who led the EC project for many years. Kruger expressed his grief regarding these invaluable, unutilised assets that had been hidden from the people.

One of the factors that hindered the utilisation of the EC films is that the EC team used 16mm film, which is difficult for people who lack expertise to handle as a storage format. In 2012, however, Nabo Simonaka and Tomoko Niwa, two Japanese curators, began to work on screening the EC films with the support of the movie theatre (Pole-Pole Higashinakano) in Tokyo that provided the equipment for projecting the 16mm film. For convenience, they also began to digitalise the EC films using telecine. Subsequently, they have held screenings and curations across Japan, inviting artists, young anthropologists, and musicians as guest speakers. The series in their project where the EC films are curated is called, ‘the EC Film Project,’ and its purpose is clearly stated on their website (http://ecfilm.net/eclab):

There are people who once dreamed of creating a magnificent film encyclopaedia...

This series of film screenings is an attempt to reinterpret and refresh the Encyclopaedia Cinematographica, the most spectacular visual archive in the 20th century, from the perspective of ‘us’ living in the contemporary world, and to breathe new life into it through the dialogues with people from various fields. We expect to find something precious and essential to our futures.

As the statement indicates, this EC Film project is re-evaluating the original intention of the EC team and unearthing a new sense of value from the EC films through dialogues with various guests and audiences.

Two curatorial organisers invited me to be a guest speaker for a screening event (‘a seven-night successive screening’) at Pole-Pole Higashinakano in December 2017 (Film 1).

Film. 1 Curating the EC Film in Japan

(Murahashi and Maeda 2020a)

This screening event comprised various subjects, such as food culture, religious rituals, and craftsmanship. I oversaw a one-night event called ‘The Nuba in Sudan: Life Changed, Heart Unchanged’. At the organiser’s request, I brought along my informant, Elnour Kowa Makki. He is a Nuba man who has resided in Japan for nearly thirty years, but his linguistic background is relatively close to the Masakin. We explained the structure of homesteads, food production, and musical instruments to the audience. We also showed four films on the Masakin: Zubereiten und Essen einer Mahlzeit, Hirseernte, Auftritt einer Sängergruppe mit Hornbläsern, and Übungsringkämpfe. Elnour Kowa Makki was born in 1960, three years before the EC film crew made these features. He explained each scene, but some were hard to understand for the non-specialist audience members, especially since they are silent films. Perhaps the direct dialogue between the audience and Elnour Kowa Makki deepened their understating of the unfamiliar social life they observed in the films.

Finally, Elnour Kowa Makki discussed the geographical remoteness of the Masakin in contrast with other Nuba groups, stating that some Nuba people (including himself) had already moved to a new town in the 1960s and were subsequently educated in the Sudanese school system. Some audience members stated that they were puzzled by this statement because it suggested that the isolated social life on screen was not always prevalent in the Nuba Mountains.

IV.Visual Repatriation of the Nuba

At this event, some of the scenes I had filmed were screened before the EC films. In September 2017, I filmed how present-day Nuba people responded to the digitalised EC films (I showed the digitalised film on DVD and as limited-access content on YouTube) as an example of the EC films’ potential for visual repatriation (Film 2).

Film. 2 Visual Repatriation of the Nuba

(Murahashi and Maeda 2020b)

The EC films concerning the Masakin’s past social life were returned to the source communities and used as foci for interviews, where the Nuba people shared narratives about their culture and history. It is still quite challenging for the outsiders to make films of the material culture and daily lives of the Nuba Mountains, while some videos which was taken by an International NGO as well as Nuba people, can be collected (Film 3).

Film. 3 The Present-day Nuba

(Murahashi and Maeda 2020c)

Since mid-2011, when new conflicts broke out in the Nuba Mountains and nearly six years of peace had ended, tens of thousands of people have fled the country. They dispersed into several refugee settlements or towns in neighbouring countries, including South Sudan, Uganda, and Kenya. The EC film screenings and interviews that they participated in were conducted in three locations: Kampala, Uganda’s capital, in September 2017; the Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement in Uganda in September 2017; and Kenya’s Kakuma Refugee Camp in September 2019. I selected a variety of individuals and groups according to age, language, and dialect. Some of the Nuba youths were suspicious of an outsider, like when I first met them in Kampala. Nonetheless, most were eager to watch the archival films from the past, which were previously unknown to them.

As the video illustrates, there was a range of responses to the film among the Nuba audiences. The Nuba youth in Kakuma was especially astounded and excited that outsiders in the 1960s recorded their ancestors. For the young Nuba individuals, who were born and raised in a Sudanese town, most of the scenes were not remembered or even witnessed by them. However, they found some similarities and continuities between the EC films and their present-day lifestyle in towns. For example, wrestling has continued and spread to Khartoum, so this is the aspect of the film that is most relatable to their modern life and interests. The Nuba people remain strongly attached to their culture and make every effort to reinforce and transmit it during their periods of exile. Cultural dances and wrestling competitions, for example, whether performed in urban or rural settings, testify to a strengthened sense of belonging and collective identity.

Meanwhile, an elder stressed how the Nuba had changed and been disrupted by the prolonged war, referring to the process of modernisation, integration into the broader Sudanese culture, and the conversion to world religions, such as Islam and Christianity. He provided detailed information on each scene by relating his childhood to the modern Nuba youth. The Nuba were keen to observe their ancestors’ actions and daily lives because of a sense of cultural loss among them. For example, the Sudanese government denies their Nuba identity. ‘They have been forced to either adapt to other societies or be exiled to refugee camps.

Intriguingly, all the audiences were eager to listen to the sound that they thought was supposed to be attached to the video. Only three films of the Masakin have sound, however, and these were not recorded in synchrony with the film. So, when I conducted the screening in the Kakuma Refugee Camp, the recorded sound was not attached to the silent film and audiences were wondering why there was no sound. They even asked the fieldworker to attach the sound to the video.

In the present era of the Internet, many Nuba peoples have filmed and uploaded scenes of cultural dances, musical performances, and wrestling competitions to enjoy and share on websites. The monothematic units of the EC films, therefore, were readily accepted by the audience, just as if they were enjoying video clips on social media.

Conclusion

While the outdated EC films have been extensively criticised, the debate over the Nuba people’s representation has largely not concerned them. The fragmentation and dispersal of many communities and the formation of diaspora communities in Khartoum has instigated a feeling of cultural loss in the Nuba people, as they have adapted to modern, urban lifestyles. Under these social conditions, the visual repatriation project demonstrates that the Nuba people seem to search for their past identity in these archival films, which strengthens their sense of belonging to the Nuba community. In the age of the internet, the EC films are as intriguing to them as other video clips that they capture and stream. Seen in this light, the ‘scientific’ and monothematic EC films may be re-evaluated in the context of visual repatriation.

Lastly, I want to convey how the EC film archive can be used for academic research in general. After the IWF closed in 2010, the full EC film archive was transferred and stored at the German National Library of Science and Technology (Technische Informationsbibliothek; TIB). I have shared my opinion with the TIB about providing online access to the Masakin film and its visual repatriation. According to email exchanges, TIB plans to provide online access to the EC’s ethnological films on an AV-Portal but only for scientific purposes (TIB AV-Portal). While anyone is free to obtain access to the TIB AV-Portal, a large number of ethnological films (including thirteen films on the Masakin) are not yet able to be viewed online. So, any person who wishes to use the EC film archive for academic purposes must first consult with TIB to obtain permission. Fortunately, TIB has a great interest in the visual repatriation of the Masakin film, which allows me to access thirteen films in a digitalised format in order to present them to the Nuba people for research.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number: JP17J09937 and International Program of Collaborative Research (IPCR) Grant Number: R1 Ⅳ-13 for the fieldwork and film-making. Regarding the utilization and copyright processing of the EC film, I was supported by the Shimonaka Memorial Foundation, the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku) and the German National Library of Science and Technology (TIB). I would like to thank Japan International Volunteer Centre (JVC) for provision of videos on the Nuba as well as Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Note

1) With the Nansen expedition, Reni Riefenstahl, a German director and photographer, visited the Nuba in Sudan. She stayed at the village even after the Nansen expedition had left, as she was highly intrigued by the Nuba’s naked body. Riefenstahl published photo albums titled, ‘Die Nuba - Menschen wie von einem anderen Stern (The Last of the Nuba)’ in 1972. Her pictures were published in a number of magazines and newspapers.

References

- Fuchs, P.

-

1988Ethnographic Film in Germany: An Introduction. Visual Anthropology 1(3): 217–233.

- Husmann, R.

-

2007Post-War Ethnographic Filmmaking in Germany: Peter Fuchs, the IWA and the Encyclopaedia Cinematographica. In B. Engelbrecht (ed.) Memories of the Origins of Ethnographic Film, pp.383–395. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Kawase, I.

-

2019Exploring the Creative Use of Germany’s Encyclopedia Cinematographica. (Senri Ethnological Studies 102), pp.157–164. Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology.

- Nannyonga-Tamusuza, S. and A. N. Weintraub

-

2012The Audible Future: Reimagining the Role of Sound Archives and Sound Repatriation in Uganda. Ethnomusicology 56(2): 206–233.

- Peers, L. and A. K. Brown (eds.)

-

2003Introduction. In L. Peers and A. K. Brown (eds.) Museums and Source Communities, pp.1–16. London: Routledge.

Films

- Luz, H. and W. Herz

-

1964Auftritt einer Sängergruppe mit Hornbläsern. Göttingen: The IWF.

https://doi.org/10.3203/IWF/E-701 - Murahashi, I. and J. Maeda

-

2020aCurating the EC film in Japan. Produced by Cat & Owl Productions, Tokyo, 4:55.

https://vimeo.com/395905074/de2ccd222a -

2020bVisual Repatriation of the Nuba. Produced by Cat & Owl Productions, Tokyo, 7:04.

https://vimeo.com/395905271/846e4401e7 -

2020cThe Present-day Nuba. Produced by Cat & Owl Productions, Tokyo, 3:26.

https://vimeo.com/395905184/cce42f4b8f

Websites

- EC エンサイクロペディア・シネマトログラフィカ [EC Encyclopaedia Cinematographica]

-

accessed January 14, 2020

http://ecfilm.net/eclab - TIB AV-Portal

-

accessed January 14, 2020

https://av.tib.eu/search?f=subject%3Bhttp://av.tib.eu/resource/subject/Ethnology&loc=en