Based on one year of ethnography in Belfast, this visual essay aims to illustrate the conceptual and theoretical potential of photographs through an exploration of various imaginaries and representations of a street, housing estate, and urban community. In the 1970s, local photographer Bill Kirk documented everyday life and urban redevelopment in the working-class neighbourhood of Sandy Row. Fifty years later, in 2018, he returned to photograph the area and its inhabitants as they faced another bout of infrastructural change. The visual material that populates this essay—the product of our collaboration—reveals a neighbourhood that has long been entangled within continuous redevelopment cycles. Employing techniques such as juxtaposition and sequencing, I suggest that the photographs of Sandy Row disrupt linear representations of time, challenging binary oppositions between ruination and regeneration and progress and decay, and laying bare the multiple and diverse temporal rhythms of capitalism (Bear 2016). This study draws on the open-ended and emergent qualities of photographs to expand, integrate, and adapt the knowledge and uses of the visual, particularly within urban contexts.

Key Words photography, time, redevelopment, community, Belfast

Streets Are Not Communities: Visualising Redevelopment in Belfast

(Published March 27, 2024)

Abstract

1. Warps and Wefts

The above photographs were captured in Sandy Row, a Protestant-Unionist district of Belfast. The image on the left was captured in the early 1970s by Bill Kirk, a documentary photographer from a nearby at the time, Sandy Row and its inhabitants were on the cusp of a restructuring programme that sought to address widespread infrastructural decay. Looking at the crumbling backyard walls, we imagine the housing conditions as cold, damp, and bleak. A history of institutional neglect aggravated the endless gloom of northern Irish weather. In Bill’s words: ‘In 1973–74, Sandy Row housing was atrocious. You could not walk past. It had to be photographed. Mrs. Elliot of Boyne Square said to me: “Show what the landlords do to us, son”’. The city council’s solution, as is often the case, was wholesale demolition. Spurred by the looming threat of violent transformation, Bill set out to document everyday life in Sandy Row. Older residents often speak of the regeneration programme as a turning point; by the 1980s, thousands of people were permanently displaced, disrupting the area’s thriving economic life, longstanding social ties, and the security of those who remained. The image on the right was captured relatively recently. Nearly 50 years later, in 2018, Bill returned to photograph Sandy Row and its inhabitants as they faced another bout of infrastructural change. This time, however, he was accompanied by his friend and fellow photographer Frankie Quinn. Through Frankie’s encouragement, Bill decided to revisit the neighbourhood, and through my friendship with Frankie, I—a then-rookie anthropologist undertaking fieldwork for my Ph.D. dissertation—became the third member of this strange little team. In a sense, the existence of the image on the right is predicated on the image on the left, but it also emerges from a different set of circumstances. As we shall see, the recursive nature of this visual project is closely linked to the cyclical nature of urban redevelopment.

With this visual essay, I aim to uncover some of the conceptual and theoretical potentials of photographs by exploring the many imaginaries and representations of Sandy Row as a street, housing estate, and urban community. Emerging from a diversity of framings and motivations, the photographs that populate this essay converge to reveal a neighbourhood that has long been entangled within continuous cycles of redevelopment. As illustrated in the photographic sequence below, Bill’s old photographs of pre-redevelopment Sandy Row tell us a linear story of loss, abandonment, and decline. However, photographs of Sandy Row captured over the decades disrupt the linear representations of time and its material manifestations. They challenge binary oppositions such as ruination–regeneration or progress–decay, ultimately revealing the uneven and multiple temporalities of urban redevelopment and infrastructural change. Weaving the pictures of Sandy Row over a long period of redevelopment reveals a murky process characterised by numerous imaginaries and fragmented representations. To this effect, I build on the growing body of work that questions the notion that the temporalities of capitalism are linear and homogenous; instead, within capitalism’s supposedly standardised temporal regimes, anthropologists have found that people engage with time in varied ways (Bear 2016; Harms 2013; Shove, Trentmann, and Wilk 2009). As argued by Morosanu and Ringel (2016), in settings of spatiotemporal inequality and conflictual experience, people try to ‘trick’ time: we try to regain a sense of control through our relationship with time (Bear 2016: 496). In this regard, Erik Harms provides a notable example in his ethnography on ‘eviction time’ in Thủ Thiêm, a ‘new urban zone’ in Ho Chi Minh City. Harms uncovered the unusual temporalities emerging in the rubble of this eviction zone, focusing on the different ways in which two groups of residents reacted to their predicaments (2013: 347). For several of the residents of Thủ Thiêm, the uncertainty of waiting impedes their ability to build livelihoods and productively organise their lives. Others, instead, respond to this enforced waiting by doing nothing, weaponising a ‘cool indifference to time that redirects the disruptive effects of waiting back onto project planners themselves’ (2013: 357). People living in this ‘presentist’ time are ‘the most troubling to the architects and linear dreamers of urban redevelopment. They do not so much refuse as remain indifferent to these future visions — their indifference to time lets them play with time’ (2013: 365).

This example indicates how time and people’s relationships with time are multiple and varied. Using the visual material that I gathered during fieldwork draws upon this conceptualisation of time as multiplicity. As Grosz writes, time as duration is ‘braided, intertwined, a unity of strands layered over each other’ (Nielsen 2014: 177). This is hinted at by the process of gathering and composing a photo essay itself. Through visual techniques such as juxtaposition, comparison, and sequencing, we can reflect upon the warps and wefts of time in Sandy Row. The mutable, unexpected, and surprising allowances of the visual offer a less linear, more layered understanding of Sandy Row as a place over time. In addition to tracing the transformation of an urban area, the photographs trace the convergence between an anthropologist and two documentary photographers. Between winter 2017 and summer 2019, I joined Bill and Frankie on a weekly walk around Sandy Row. Conceptually, this entanglement presents both challenges and possibilities. This essay builds upon and reflects on our collaboration and the ways in which our paths, our trajectories, converge and diverge alongside those of Sandy Row. Therefore, I also respond to longstanding calls to reappraise the role and possibilities of the visual in anthropology (Harper 2003; MacDougall 1997; Pink 2011). More than a methodological tool, a means of access, or supplementary illustration, photography guided the analytical process. Photographs are subjective, fractal, and open-ended; they open things up by leaving things open. To create space for these emergent qualities, the visual material within this essay will be uncaptioned, and a reference for each image will be included at the end of the essay.

2. Return to the Row

Like several other working-class areas of Belfast, in the 1970s and 1980s, Sandy Row was hit with a major restructuring programme. While the citywide redevelopment programme sought to address people’s abject living conditions, these efforts were seldom informed by the needs of the local population. In the 1960s, proposals to replace terrace houses with high-rise flats were met with outrage by Sandy Row residents who feared the integrity of their homes and their community. A Redevelopment Association was formed to resist the proposals. After some important victories, the association campaigned for community-led redevelopment. However, repeated delays resulted in the deterioration and collapse of several houses. By the 1980s, Sandy Row’s dilapidated housing had been more than halved, with the slow closure of most of its shops and pubs and the lack of housing and employment in the area resulting in the displacement of over two-thirds of the population to the suburbs (McCann 1997: 96).

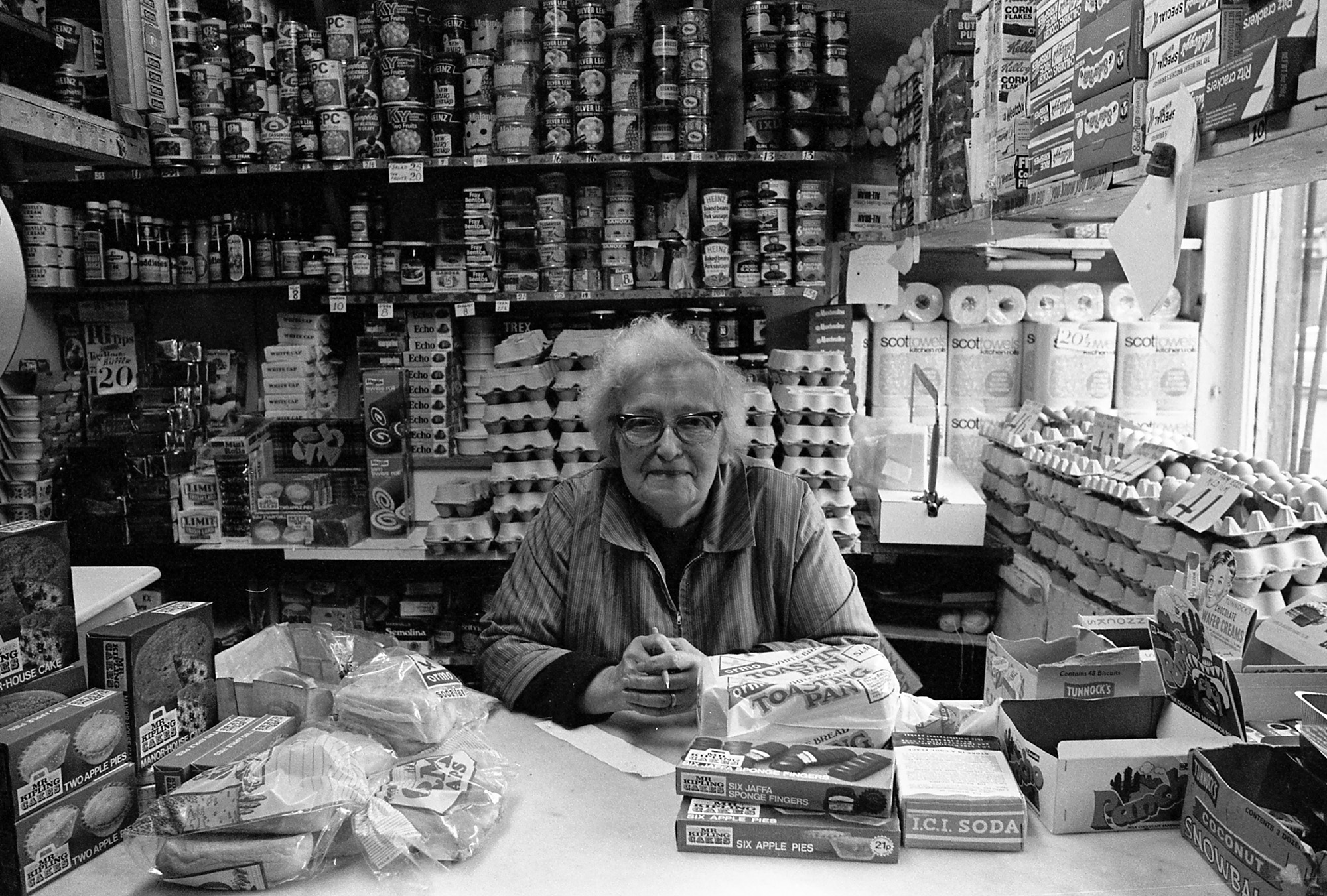

Bill Kirk’s photographs of 1970s Sandy Row were motivated by the looming erasure of top-down urban redevelopment. His intuition proved to be correct; the district was irrevocably transformed, and his photographs proved it. In an article tracing the development of photographic representations of working-class lives from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s, Newbury (1999) noted that documentary photographers in Britain commonly focused on the effects of urban redevelopment. Much like Bill, Frankie, and several others who took pictures in Belfast during those decades, photographers were concerned with representing specific historical and cultural milieus during times of social change (Newbury 1999: 21). These photographic practices resonate with the aims of what Clifford referred to as ‘salvage ethnography’ (1986), as they sought to ‘save both visually, and literally in some cases…communities that are about to disappear’ (Newbury 1999: 22). Several of these photography projects were spurred by the sense that the spectre of social death loomed over these urban spaces, and that a particular form of sociality and community would disappear alongside their unique political potential.

Bill’s eventual return to Sandy Row resulted from his friendship with photographer Frankie Quinn. Over the years, Frankie digitised Bill’s immense back-catalogue of negatives and created a series of exhibitions and publications. Frankie’s archival work was guided by a commitment to working-class communities as subjects and audiences of visual practice. He aimed to re-embed the photographs back into the communities where they were taken and, through them, elicit and gather family and personal histories, thus ‘reactivating’ Bill’s photographs from the 1970s (Edge 2015). In this instance, the project was pushed even further: from the ‘archival’ and historicised images of pre-redevelopment Sandy Row emerged the idea of returning not just the photographs but the photographer himself. This new documentary photography project was named Return to The Row. In addition to collecting local histories from older inhabitants, Bill—now in his mid-eighties—was to photograph the area, just as he did in his youth. The City Council-backed Sandy Row Community Forum supported the project. At a preliminary meeting with Glenda, the Forum’s administrator, we learned that she wanted Frankie and Bill to document Sandy Row and its residents as they underwent a new phase of redevelopment. Ultimately, she hoped to use Bill’s return to Sandy Row to encourage local support for future redevelopment projects and even help restore Sandy Row’s originally displaced population. As she explained:

I want to try capture things as they are now, before they change. It’s a marketing tool, this, to try and capture the moment and make sure people are aware of what’s happening and why. We also want to encourage those who had left during redevelopment to come back. So…it’s exciting.

Glenda’s words illustrate how the past manifests itself in future imaginaries for Sandy Row: this is a place in a continuous state of decline, but also of becoming and possibility. In contrast to her optimistic outlook, Bill’s return to Sandy Row was laced with apprehension about the area’s future. Why would this time around be any different?

Several Sandy Row residents continue to blame redevelopment for the decline of their estate. Another key factor was that Belfast was the main site of the war between paramilitary groups and the British Army known as the Troubles1). After 'threTRAJe' decades and over 3,700 deaths, armed conflict came to an ‘official’ end with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. In Northern Ireland, economic inequality is often overshadowed by political divisions and ethno-national belonging. People’s identification as British or Irish is often expressed through the shorthand of Protestants (commonly viewed as the descendants of colonial settlers) and Catholics (the descendants of the indigenous population). Within these ethnic boundaries are categories that refer to political ideology. In the simplest of terms, Republicans and Nationalists strive for a united Ireland, whereas Loyalists2) and Unionists are characterised by their political allegiance to Britain and opposition to Irish unification. Most of Sandy Row’s inhabitants identify as the latter. Especially at the beginning of the conflict, the area was the base for the most active and notorious sections of the Loyalist paramilitary group known as the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). These violent legacies have lingered. To this day, Sandy Row is characterised as a monolithic and ‘staunch’ Loyalist district in local and institutional discourse. As Belfast’s most disadvantaged neighbourhoods were the most affected by the conflict, they are also often framed as being suspended in a perennial state of transition—from a ‘time of war’ to a nebulous ‘time of peace’—and have little chance to define themselves outside that binary. Since the end of the Troubles, inter-ethnic segregation has worsened and crystallised alongside community, neighbourhood, and the urban landscapes of which they are a part. However, Sandy Row – the road that gives the surrounding housing estate its name – was once a bustling shopping street frequented by working-class people on both sides of the ethnic divide. With the restructuring of the housing estate and the conflict solidifying paramilitary territoriality, the street and surrounding estate fell into physical and socioeconomic disconnection. As we shall see further, local and institutional perceptions of Sandy Row’s decline and marginality are closely associated with its homonymous street’s trajectories and transformations.

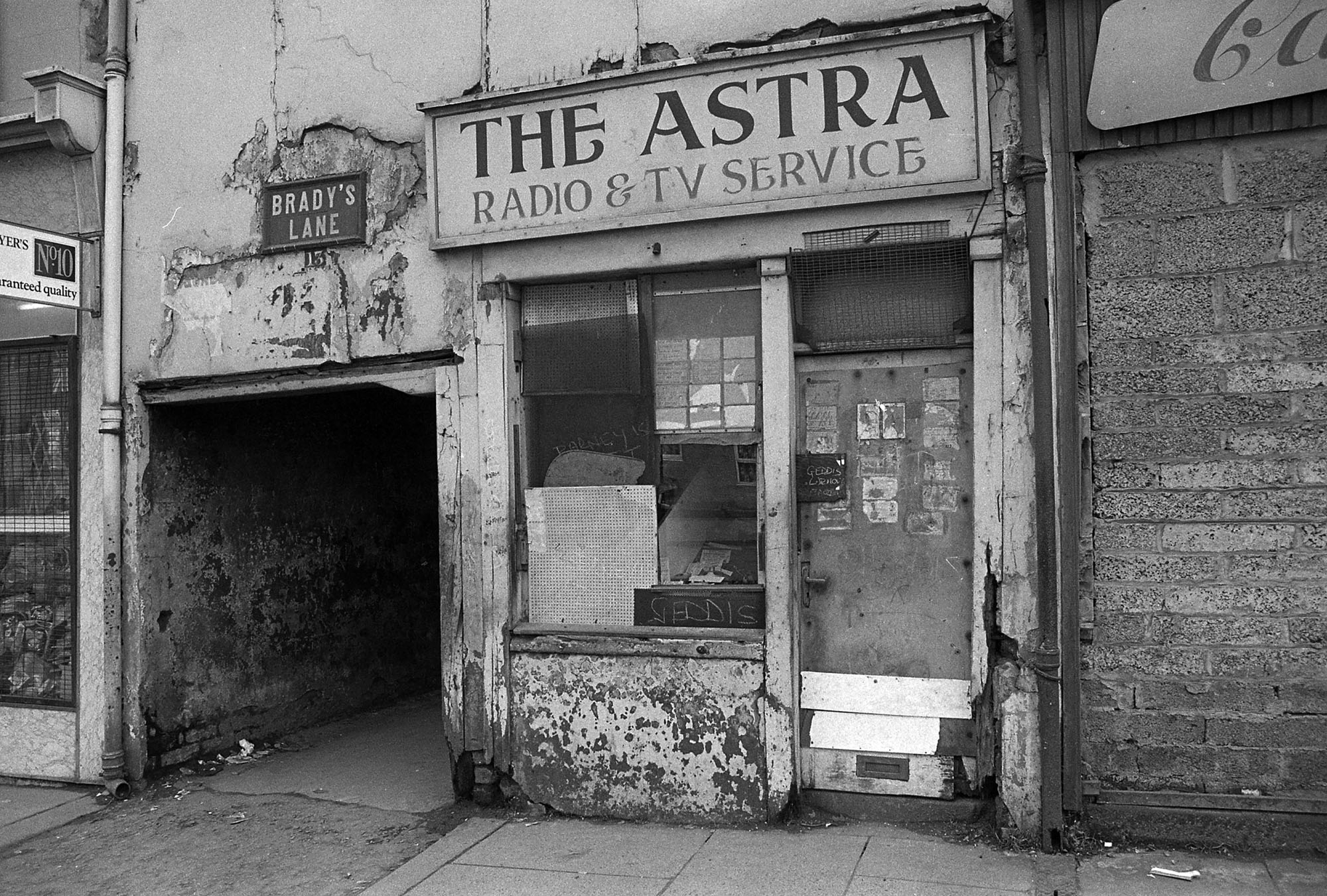

In temporal terms, Sandy Row exists in the aftermath of conflict, demolition, and displacement (Gordillo 2014). The process extended over time; houses slowly crumbled and were unevenly and messily knocked down over several years. As Dace Dzenovksa (2020: 22) notes, ‘depopulation, ruination, and abandonment are not new in the history of capitalist industrialisation and modernisation. They tend to be folded into theorisations of capitalist development as inherently messy’. One example of these theoretical frameworks is the early 20th -century political economist Joseph Schumpeter’s influential notion of ‘creative destruction’, arguing that progress and destruction go hand-in-hand. However, when placed side by side, the photographs of Sandy Row in the 1970s and 2010s do not necessarily indicate a linear trajectory of ruination and decline, but, rather, they index varied outcomes. The cycles of urban redevelopment resulted in leftovers and left-behinds. According to Dzenovska and Knight (2020), ‘the time between the old world ending and the new world not yet beginning is not empty in an absolute sense. As Frank Kermode (2000) suggests, the momentary emptiness between a clock’s ‘tick’ and ‘tock’ is crammed with speculation and anticipation (Bryant and Knight 2019: 79)’. People in Sandy Row have been living between this ‘tick’ and ‘tock’ for a long time. To this day, they face the uncertainties of future infrastructural change and displacement. The impetus to go out and photograph the area, ‘to capture things as they are now before they change,’ is, once again, dictated by these emergent futures and the possibility of destruction and erasure. Photography’s ambiguous trans-temporal nature lends itself well to a study of time and infrastructure within capitalism: weaving the images of Sandy Row ‘then’ and ‘now’ reveals the uneven temporalities of urban redevelopment and how these may be variously represented and narrated. In other words, these photographs question any one representation and imagination of Sandy Row’s past, present, or future. Rather than static surfaces, the photographs are as fluid as the environments from which they emerge: as Sarah Pink (2011) puts it, ‘They cannot take us “back” but are part of new “constellations of processes” (Massey 2005) …they are “both emergent from, and implicated in the production of, the event of place”’.

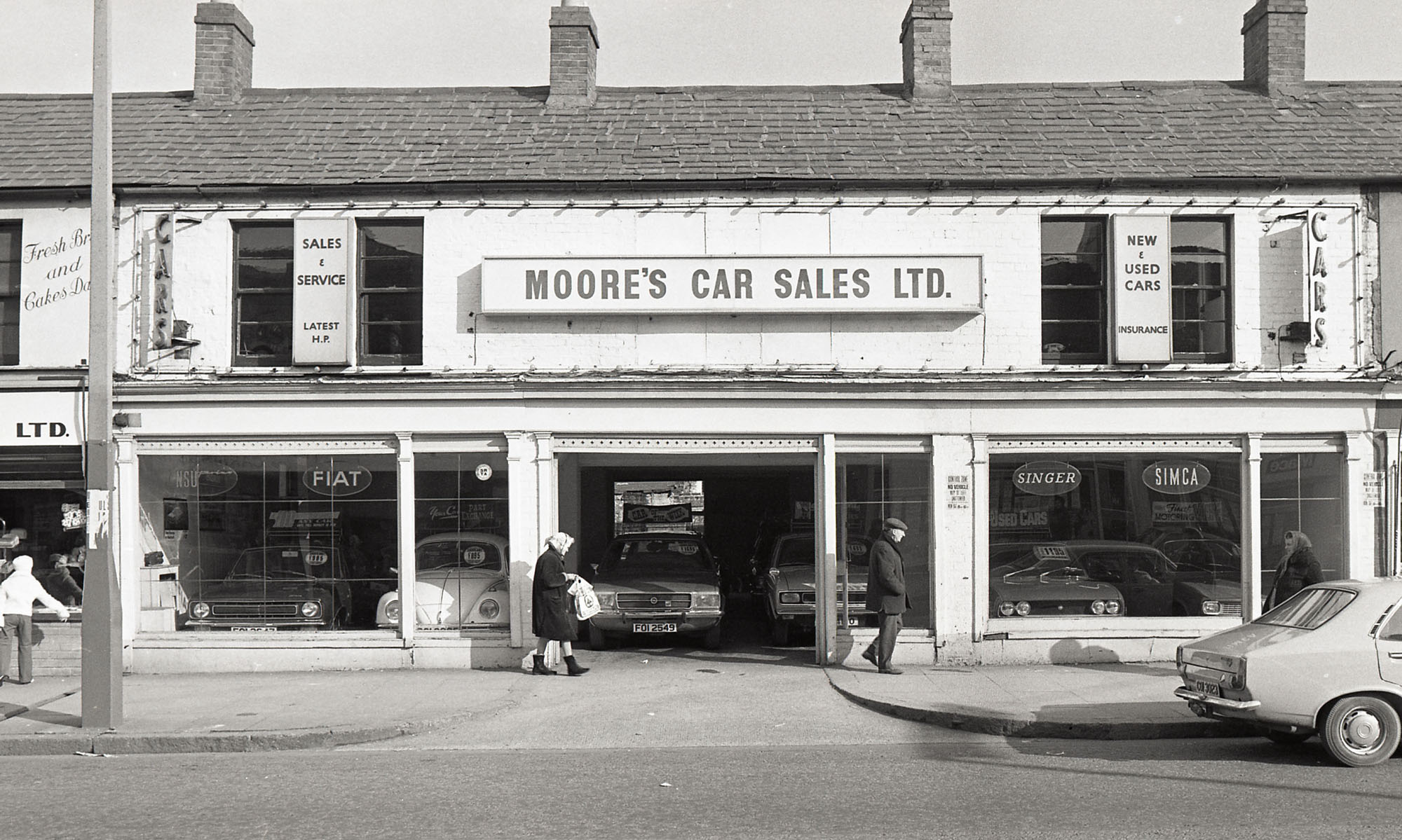

In his study of time and infrastructure, Akhil Gupta conceptualises infrastructures as a ‘thing-in-motion, ephemeral, shifting, elusive, decaying, degrading, becoming a ruin but for the routines of repair, replacement, and restoration (or despite them)’. Rather than being linear—beginning with planning, ending with completion—Gupta frames infrastructural projects as ‘a process that is characterised by multiple temporalities, open futures, and the constant presence of decay and ruination’ (2018: 62). In this sense, we might think of the photographs of Sandy Row as indexes of past and future ruins. Consider the two photographs above. The one on the right was captured on a cold December day in late 2018. This is among the most dilapidated stretches of Sandy Row. There are all kinds of writing: the faded capitalised font of the old shop sign, graffiti tags, and scrawled initials of the Ulster Defense Association (UDA). Abandoned by humans, pigeons nest on the rotting roof beams. Juxtaposed is an older photograph of a shoe shop that used to sit at the top of Sandy Row’s main street. Adjacent to the empty, derelict street on the right, this photograph narrates a story of economic activity and human presence. However, alongside the bustling shopping street, Bill also documented widespread state neglect by photographing crumbling housing, outhouses, and the rubble of demolition. Juxtaposing one photograph with an image of street life (below) reveals the uneven temporalities of infrastructure and urban change. The Forum wanted to use Bill’s images of 1970s Sandy Row to remind residents that, before state intervention, housing conditions were unacceptable. Instead, in the context of this visual essay, the same photographs are employed to challenge the linear binary opposition between urban ruination and regeneration, progress and decay. These images are mutable and polysemic: they are nostalgic records of a bygone era, indexing how much things have since improved, how things have declined, and how, between the ‘tick’ and ‘tock’ of urban redevelopment, the residents of Sandy Row continue to live their lives.

3. Streets Are Not Communities

I just think, to be honest with ya, people moved away. Sandy Row’s not what it used to be. Sandy [sic] used to be a community. (Conversation with Tracy. May 2019)

Bill Kirk’s enduring fascination with shopkeepers and shopfronts picks up and amplifies the imagination of the street as a hub for sociality and economic life. In the 1970s, he captured each shopfront and building from one end of the street to the other. The photographs were assembled in lines across several tables in a photo-elicitation session with older female residents. The women shuffled and moved the pictures, reassembling them with memories of the old streetscape: ‘Ooh, look at that!’, ‘Oh look, there’s John Brown!’, ‘The butcher?’, ‘He drove from Ballymena every day, did you know?’ People’s names and faces were identified with excited yelps, and stories and recollections were evoked alongside comparisons. While everyone agreed that living conditions had vastly improved, a sense of sadness prevailed: ‘Ah, Sandy Row is a disgrace now, so it is,’ one of them sighed. Indeed, the political critique of memory and nostalgia-driven narratives frames these neighbourhoods as stuck within a progressive and linear state of decline and ruination. By contrast, I suggest that the photographic representations of Sandy Row are open-ended, allowing for a more expansive understanding of the idea of ‘community’. Where do the community and this street begin, and where do they end? How do the discursive framings of Sandy Row’s population and infrastructure relate to this visual material, and how might this visual material dislodge them?

For some time, anthropologists have acknowledged the contingent relationship between roads and their socioeconomic environments (Dalakoglou 2017; Harvey and Knox 2012; Pedersen and Bunkenborg 2012). These perspectives draw attention to the multitude of temporalities specific to the social, economic, and political environments of which infrastructure is a part and, crucially, challenge essentialising notions of place (Massey 1995). Drawing on these approaches, a street becomes more than a simple connector within a network but rather a ‘lively’, dynamic, and relational entity, making it the perfect microcosm to explore constantly evolving social relations. Sociologist Suzanne Hall, for instance, combines conventional ethnographic methods with visual and spatial analysis to explore every-day life in Walworth Road, a functionally central yet socially and economically marginal district of southeast London. She uses juxtaposition, collage, and layering ‘as both illustrative forms and analytic methods for observing and representing difference’ (Hall 2010: 2). Hall argues that while Walworth Road is physically connected to the centre of London, it also maintains a unique local cultural resonance that is not legible to the casual passer-by. Others, by contrast, have tried to steer clear of specificity. In a paper presented at the Tate Modern in 2005, Daniel Miller discussed his study of a street in North London. (Miller 2005; UCL ANTHROPOLOGY). At the beginning of the study, he set out to deliberately find a nondescript street that represents no person and no group—a ‘whatever’ area, so ordinary as to be hard to describe. Miller explained that this was motivated by an anthropological quest for unfamiliarity and ignorance aimed at an ethnographic approach unsaturated by theoretical discourse. Miller highlights the discourse of the street as a particularly powerful and pervasive trope in Britain: ‘We live the discourse of the street, the fantasy of community, of the neighbourhood, of history, of local identity, of street festivals, street complaints, street parking, and of corner shop’. From this, he is concerned with answering the problem of what defines a London street and how the street is imagined ‘articulates with the experience of actual households, my eclectic collection of fortuitous juxtapositions that is any actual street, my particular, nothing in particular, non-descript street’. This study found that streets in most cities should not be assumed as communities.

In Sandy Row, a segregated urban district in Northern Ireland, the boundaries between streets and communities are particularly nebulous. None of its streets fit the bill of ‘ordinary’, ‘nondescript’, or 'whatever' areas, as Loyalist murals and British flags loudly proclaim unordinariness and the area’s ethno-national allegiances. The street and surrounding estate are defined by insiders and outsiders by its distinctly Protestant-Unionist population and history. Although it is not a ‘whatever’ place, I would argue that Sandy Row’s varied specificities and manifestations over time distance it from pre-determined concepts and theorisation. To break through these limiting framings, I summarise the multifaceted and sometimes contradictory nature of photographs as a means through which a place may or may not represent a singular thing. These contradictions and the tenuous relationship between locality and community are especially apparent when residents describe Sandy Row as a ‘ghost town’, a place at death’s door. One participant, a middle-aged woman named Tracy, described the joys of living close to so many of her family members and then, in the same breath, added that she was too afraid to leave the house. Younger folk, like Tracy’s daughter Nicole and her friends, would also make contrasting observations: ‘Sandy Row is dead’ and an ‘absolute shithole’ would go alongside statements such as ‘I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else’ or ‘I could never leave’. Of course, this was also due to the lack of jobs and mobility—financial, social, and physical—that accompanies it.

This language—of ghostliness, disconnection, and vacancy—has recently been explored by anthropologists through the concept of ‘emptiness’. In the context of emptying Latvian towns and villages, Dzenovska (2020) understands this specific configuration of capitalism as resulting in a disconnection between people and places: ‘Nobody is promising better futures to those living in the emptying villages—at least not if they stay put—because the people and places do not have a future together’. However, for all the talk of gloom and ghosts, Sandy Row and its streets are far from empty. This is most evident when the streets become party venues over the yearly Twelfth of July celebrations.

The Twelfth of July revolves around the victory of Protestant King William against Catholic King James at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. This historic battle played a key role in securing Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland and, as such, is at the heart of Loyalist/Unionist discursive and symbolic practices. Several aspects of the Twelfth are celebratory and carnivalesque, as they are intimidating and divisive. One year, Nicole invited me to join her and others in the festivities: ‘Welcome to the ghetto!’ She bellowed when I arrived with my bag of beer and the cordial she had requested. A few hours before the climax of the celebrations—a large and controversial bonfire (Poloni 2021) —we joined a boisterous parade around the estate. This was an internal, exclusive event within the enclosed confines of what one resident once described as a ‘rabbit warren’. The crowd of mostly young residents squeezed through the estate’s tight alleyways, hopping, clapping, and chanting through the estate as older folk looked on, grinning. Finally, we stopped before a memorial for a young man who had died from an accidental drug overdose. ‘It was a real shock’, Nicole explained over the blaring music. ‘He was a nice lad’. Before I could ask for more details, the crowd suddenly erupted into a roar. Eyo! Eyo! We are the Billy Boys! We’re up to our knees in Fenian3) blood, surrender, or you’ll die!

These street parties are fun, cathartic events, and, as we can see from Bill Kirk’s photographs of the July celebrations back in the 1970s, they are nothing new. However, as the lyrics above illustrate, these parades are also tied to the discourses of the wider Loyalist community and the legacies of violence, sectarian division, and territoriality. These practices support a visualisation of Sandy Row as a ‘sectarian’ community that is stuck in the past and has no place in the city’s future. In such a context, the progress-oriented visions of top-down urban redevelopment risk complicating the ongoing realities of segregation and deprivation and entrenching the more troublesome and exclusionary local understandings of ‘community’. Other local articulations of community are geared towards outsiders. This is best illustrated by Jim, a lifelong resident of Sandy Row who runs a small walking tour. Jim takes visitors to the old tobacco factory, now high-end offices, and where the linen mills used to be, weaving a tale of a proudly Protestant working-class community impacted by war, de-industrialisation, and ill-fated redevelopment programmes. In his tours, Jim’s narrative of Sandy Row predominantly focuses on local involvement in the two World Wars. It does not mention its darker and more recent histories, if not by framing Sandy Row as a community that has survived and defended itself against attacks by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Like several other residents, Jim was worried about the area’s future. One afternoon, Bill, Frankie, and I drank a cup of tea with Jim and a few other local men; his friend John described the street where he was born: ‘The old community…there’s nothing left of it. Hundreds of people were there, but then the houses fell into disrepair… We were one of the last families. See now? It’s a ghost town. You don’t even know!’ He shook his head despondently. ‘There was a whole community there, Jim added: ‘It’s only a matter of fact this place is gonna disappear if we don’t fight for it now, cause it’s so close to the city centre. Never mind the money! What about the future?’

Drawing on her fieldwork in a neighbourhood of Beirut, Joanne Nucho (2016) illustrates how everyday sectarian belonging is constructed and reconstructed in dialogue with urban infrastructure. Nucho suggests that far from monolithic, primordial ‘sectarian’ communities, these groups are as malleable as the infrastructures in which they are embedded. In this sense, the many definitions, framings, and nebulous boundaries of Sandy Row point to the idea that urban communities are not crystallised. Their visual representations are open to various imaginaries and appropriations. In the case of the Return to the Row project, photographs were mobilised to foster a community in the face of a difficult past and uncertain future. However, like the idea of community, the photographs are not fixed. Rather, they are indexes of the present and absent, what is and is not, what was, what will be, and what could be. If we view urban populations or ‘publics’ as being constituted with and through infrastructure (Anand, Appel, and Gupta 2018), visual ethnographic attention to, in this instance, a street and its formations recognises that infrastructure, material environment, publics and politics are relational and emergent. In the aftermath of redevelopment, the discourse of the street and the fantasy of community become fractured and ambiguous. Photographs of the street and its people are part of the uneven landscapes of inclusion, exclusion, and imaginaries of the past; as I shall discuss next, they might actively contribute to how the future may be imagined and called upon.

4. Breaking the Cycle

The visual material that populates this essay results from an urge to capture and analyse a place embroiled in ongoing cycles of urban redevelopment. From the moment they are created, the images are re-embedded in the next cycle of urban change. Far from straightforward or linear, my use of Bill’s photographs and our respective projects bounce back and forth in time. Historical photographs of 1970s Sandy Row were often used while creating a photographic record and ethnographic study of the area. The documentary photographers and I operated within separate yet intertwined traditions, our concerns and motivations both coinciding and differing. By collecting oral histories and creating a new photographic record of Sandy Row, Bill and Frankie sought to re-embed the past within the present and salvage it from an uncertain future. By contrast, I was concerned with how past, current, and future cycles of urban redevelopment influence residents’ sense of community and belonging. However, we also took leaves out of each other’s books. Their project was informed by ethnographic sensibility, and my involvement in the Return to the Row project shaped mine. Our presence in Sandy Row over 50 years was similarly dictated by emergent futures and the looming possibility of infrastructural change. The appearance of researchers and photographers in neighbourhoods such as Sandy Row is foreboding. In this sense, more than records of the past, the photographs within this essay could also be read as a warning of things to come.

The destruction and reconstruction of Sandy Row was slow and protracted. Even before redevelopment, the area’s disrepair was not a sudden ‘event’ (Povinelli 2011). The displacement of the population and the closure of shops were similarly slow, but they could not be reduced to a linear process of decay and disconnection. Older photographs are indexical of a lively residential area and bustling shopping streets, depending on how they are contextualised and sequenced. As the housing conditions in Bill’s photographs indicate, they show that state neglect long predated its ruinous redevelopment programme. As Chu writes, in the redevelopment process, disrepair ‘sits murkily between ruination and renovation’ (2014: 353). These photographs are snapshots of moments in time, but when placed side by side, we can glimpse the space in-between. It is within this space that a community’s boundaries are drawn and redrawn. Rather than thinking of Sandy Row as only one thing or the street as a metonym for community, I have drawn on understandings of infrastructure as fluid and emergent, grounded in the specificities of place and time. As Harvey and Knox (2015) highlight, a huge gap exists between the future promises of large-scale infrastructural projects and how these intentions play out in practice. The estate’s redevelopment and solidifying ethno-nationalist territorial boundaries precipitated Sandy Row—the street, the estate, and the community—into a physical, political, and socioeconomic disconnection. This idea is echoed by Holbraad et al.’s (2019) discussion of ‘rupture’ as a radical form of discontinuity, a break between existing conditions. They caution against recent theoretical inclinations that frame discontinuity in a positive light and as the moment at which the new can creatively emerge. As they write,

By paying attention to the mutual constitution of discontinuity and renewal in specific ethnographic settings allows us to offer alternatives to the revival of Schumpeter’s notion of ‘creative destruction’ in sometimes wide-eyed contemporary debates about disruptive innovation. How ruptures are evaluated by the people caught up in them and how these evaluations emerge and interact with one another are for us open ethnographic questions (Holbraad, Kapferer and Sauma 2019: 2).

Disconnection, ‘emptying’, and uneven spatial development are discussed as normal, even central features of capitalist cycles of growth and decline: on the path to progress, there is always destruction. From this perspective, Sandy Row and its residents appear to have fallen between the cycles of post-conflict capitalist development. Ongoing legacies of conflict, territoriality, and segregation complicate these processes. The discursive frames of new road developments depict Sandy Row as an abandoned place that, as Dzenovska explains, ‘should be reintegrated into global circuits of economic and political power or as sites of world-making that conjure up hopes for alternative futures’ (2020: 26). However, these are not homogenous and routine cycles—the specificity of different ethnographic and historical contexts allows us to analyse the ‘shifting contours of global capitalism, state power, and associated ideologies’ (Dzenovska 2020). The temporalities of redevelopment are cyclical, ongoing, and always aligned with the inevitable decay of urban infrastructure. But what lies in the offbeat between destruction and creation? More than a linear progression from decay to regeneration, destruction, and construction, the visual material that populates this essay suggests that these cycles are overlapping and incomplete. Chasing their own tail, they are also never-ending. In other words, the conditions Bill and other documentary photographers recorded in the 1970s and the 1980s have not disappeared; they have taken a different form.

This essay illustrates how photographs can be mobilised to serve analytical and conceptual aims. When talking about time, words reach where images cannot: they contextualise, structure, and assess. The photographs speak to time in a way that is beyond the reach of words. This quality lends itself to exploring the imaginary and temporal aspects of urban redevelopment. The photographs of Sandy Row over the decades and the ways in which they are mobilised might also act as stepping stones towards alternative future imaginaries. Disrupting linear representations of time supports the idea that these cycles of ruination, regeneration, destruction, and construction are not inevitable. As in several cities worldwide, when it comes to participation in the planning process, local authorities disregard residents’ proposals and campaigns and impede the possibility and imagination of alternative futures. To regain some sense of control, residents in areas such as Sandy Row might become entrenched and turn to troubling expressions of community and belonging. However, several alternatives exist. In Community-Led Regeneration: a Toolkit for Residents and Planners (2020), Sendra and Fitzpatrick from UCL’s Department of Planning offer a practical guide for residents whose homes face an uncertain future. Drawing on seven case studies from London, they identify a combination of formal and informal strategies through which residents can effectively oppose demolition and propose alternative plans. The strength of a campaign requires strong networks, access to support, and the exchange of knowledge between resident groups. The residents of Belfast face the additional obstacles of spatial segregation, contestation, and deeply felt political affiliations. How these specificities might be engaged and not overlooked while building the capacity for community-led regeneration is an important topic for further research. I conclude by noting that, in the context of cities, ‘regeneration’ usually refers to the place-making practices and discourses of top-down urban interventions. Alongside the emergent potential of photography, I call upon the more expansive and semi-metaphorical resonances of ‘regeneration’—as a process through which things are disposed of, re-made, transformed—to inform our understandings of the past, belonging, community, and, ultimately, our visions of the future.

Acknowledgements

This article would not exist without Bill Kirk and Frankie Quinn from the Belfast Archive Project. Thank you for having me on board the Return to the Row project and for your friendship and support over the years. I extend special grati-tude to Bill, whose wonderful photography forms the backbone of this article. It was a rare privilege to learn from you, see you in action, and spend time with you over so many Wednesdays in Sandy Row. I am also deeply grateful to the people of Sandy Row for welcoming me into their neighbourhood and sharing their thoughts, lives, and time with me. This research was funded by the Arts and Humanities Council Doctoral Training Partnership.

Notes

- 1)

- The first deaths in 1969 are generally understood as being caused by political, economic, and social tensions that had been deepening for over a decade. Sectarian divisions date further back to the partition of Ireland in 1921, which granted independence to the Catholic (Nationalist/Republican) majority in the south while securing a Protestant (Unionist/Loyalist) majority in the northeast. This precipitated a ‘double minority syndrome’ (Bollens 2018), whereby Protestants are a minority within the island of Ireland threatened by the possibility of a united Ireland and Catholics are a minority within Northern Ireland threatened by British direct rule.

- 2)

- In Northern Ireland, Loyalism is often understood as the armed, working-class side of political Unionism. The term is linked to class divisions within the wider Protestant community and is commonly adopted by several working-class Protestants.

- 3)

- In this context, ‘Fenian’ is a disparaging term reserved for members of the Catholic/Republican/Nationalist community.

Photo Credits

Figure 1

Figure 1 Bill Kirk

(1973)

Figure 2

Figure 2 Bill Kirk

(2018)

Figure 3

Figure 3 Anna Poloni

(2019)

Figure 4

Figure 4 Bill Kirk

(1973)

Figure 5

Figure 5 Bill Kirk

(1973)

Figure 6

Figure 6 Bill Kirk

(1973)

Figure 7

Figure 7 Bill Kirk

(2018)

Figure 8

Figure 8 Bill Kirk

(1972)

Figure 9

Figure 9 Bill Kirk

(2018)

Figure 10

Figure 10 Bill Kirk

(2018)

Figure 11

Figure 11 Bill Kirk

(1972)

Figure 12

Figure 12 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 13

Figure 13 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 14

Figure 14 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 15

Figure 15 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 16

Figure 16 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 17

Figure 17 Bill Kirk

(2018)

Figure 18

Figure 18 Bill Kirk

(2018)

Figure 19

Figure 19 Bill Kirk

(2018)

Figure 20

Figure 20 Anna Poloni

(2019)

Figure 21

Figure 21 Anna Poloni

(2019)

Figure 22

Figure 22 Anna Poloni

(2019)

Figure 23

Figure 23 Anna Poloni

(2019)

Figure 24

Figure 24 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 25

Figure 25 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 26

Figure 26 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 27

Figure 27 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 28

Figure 28 Anna Poloni

(2019)

Figure 29

Figure 29 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 30

Figure 30 Bill Kirk

(1970s)

Figure 31

Figure 31 Anna Poloni

(2019)

References

- Ahmed, S.

- 2004

- The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Anand, N., H Appel, and A. Gupta (eds.)

- 2018

- The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bear, L.

- 2016

- Time as Technique. Annual Review of Anthropology 45: 487-502.

- Bollens, S.

- 2018

- Trajectories of Conflict and Peace: Jerusalem and Belfast Since 1994. New York: Routledge.

- Bryant, R. and D. M. Knight

- 2019

- The Anthropology of the Future. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chu, J.

- 2014

- When Infrastructures Attack: The Workings of Disrepair in China. American Ethnologist 41(2): 351-367.

- Clifford, J. and G. Marcus

- 1986

- Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Dalakoglou, D.

- 2017

- The Road: An Ethnography of (Im)Mobility, Space, and Cross-border Infrastructures in the Balkans. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Dzenovska, D.

- 2020

- Emptiness: Capitalism without People in the Latvian Countryside. American Ethnologist 47(1): 10-26.

- Dzenovska, D. and D. Knight

- 2020

- Emptiness: An Introduction’. Society for Cultural Anthropology. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/series/emptiness (Accessed July 5th, 2023)

- Edge, C.

- 2015

- Looking for Bolton in the Worktown Archive. In Edwards, E and Morton, C (eds), Photographs, Museums and Collections, pp. 247-263. London: Bloomsbury.

- Gordillo, G.

- 2014

- Rubble: The Aftermath of Destruction. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Gupta, A.

- 2018

- The Future in Ruins: Thoughts on the Temporality of Infrastructure. In Anand, N., Gupta, A, and Appel, H (eds.) The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hall, S.

- 2010

- Picturing Difference: Juxtaposition, Collage and Layering of a Multi-Ethnic Street. Anthropology Matters 12(1), 1-17.

- Harms, E.

- 2013

- Eviction Time in the New Saigon: Temporalities of Displacement in the Rubble of Development. Cultural Anthropology 28(2): 344-368.

- Harper, D.

- 2003

- Framing Photographic Ethnography: A Case Study. Ethnography 4(2): 241-226.

- Holbraad, M., B. Kapferer, and J. Sauma

- 2019

- Ruptures: Anthropologies of Discontinuity in Times of Turmoil. London: UCL Press.

- Joniak-Lüthi, A.

- 2020

- A Road, a Disappearing River and Fragile Connectivity in Sino-Inner Asian borderlands. Political Geography 78: 1-11.

- Kermode, F.

- 2000

- The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- MacDougall, D.

- 1997

- The Visual in Anthropology. In M. and Morphy, H (eds.) Rethinking Visual Anthropology. pp.276-295.

London: Yale University Press.

- Massey, D.

- 1995

- A Global Sense of Place. Place, Space and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- 2005

- For space. London: Sage.

- McCann, D.

- 1997

- The Row You Know: Memories of Old Sandy Row. Belfast: Sandy Row Community Centre Committee.

- Miller, D.

- 2005

- Une Rue du Nord de Londres et ses Magasins: Imaginaire et Usages. Ethnologie Française 35: 17-26.

- Morosanu, R. and Ringel, F.

- 2016

- ‘Time-Tricking: a General Introduction’. Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 34(1).

- Newbury, D.

- 1999

- Photography and the Visualization of Working-Class Lives in Britain. Visual Anthropology Review 15(1): 21-44.

- Nielsen, M.

- 2014

- A Wedge of Time: Futures in the Present and Presents Without Futures in Maputo, Mozambique. Journal of The Royal Anthropological Institute 20(S1): 166-182.

- Nucho, J.

- 2016

- Everyday Sectarianism in Urban Lebanon: Infrastructures, Public Services, and Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Pedersen, M. and M. Bunkenborg

- 2012

- Roads that Separate: Sino-Mongolian Relations in the Inner Asian Desert. Mobilities 7(4): 555-569.

- Pink, S.

- 2011

- Doing Visual Ethnography: Images, Media and Representation in Research. London: Sage Publications.

- Poloni, A.

- 2021

- Bonfire Time in Belfast: Temporalities of Waste in a Loyalist Neighbourhood. Etnofoor 33(2): 112–132.

- Povinelli, E.

- 2011

- Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Sendra, P. and D. Fitzpatrick

- 2020

- Community-Led Regeneration: A Toolkit for Residents and Planners. London: UCL Press.

- Shove, E., F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk

- 2009

- Time, Consumption, and Everyday Life: Practice, Materiality, and Culture. London: Routledge.

Websites

- UCL ANTHROPOLOGY

- Thinking a North London Street: Daniel Miller, at the Tate Modern

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/anthropology/people/academic-and-teaching-staff/daniel-miller/thinking-north-london-street (accessed July 26, 2023)

Contact

Anna Estel Poloni

*Replace “■” with “@”.