This paper argues for greater and more critical engagement with creative visual communication in ethnographic research with/for linguistically and culturally diverse groups of young people, such as those who have been forcibly displaced across borders. It is based on eight months of doctoral fieldwork with displaced youth in Thessaloniki, Greece, during which the author aimed to better understand their educational decision-making in a context of ‘unsettlement’. This involved participant observation as a volunteer teacher in various educational spaces (including language classes and arts workshops); and individual and group interviews (involving creative methods) with youth aged 15-25 and other educational ‘stakeholders’. The paper addresses various ways in which creative visual communication (specifically, drawing) became a part of this project – as the setting, a method and a form of dissemination – and offers reflections on its associated challenges, possibilities and responsibilities. It argues that when used with critical reflection, drawing has the potential to transgress both physical and social borders among youth, anthropologists and the wider public.

Key Words illustration, youth, refugees, ethnography, creative visual communication

Drawing (Across) Borders: Reflections on the Use of Creative Visual Communication in Ethnographic Research with/for Young Refugees

(Published March 27, 2024)

Abstract

Introduction

The boys were working on their third drawing, of themselves in 5-10 years’ time. Reza, 16, drew two figures in his picture: one of himself as a bank clerk, and one as a footballer. I asked him if he’d drawn two options because he couldn’t decide what he wanted to be. He shook his head and explained that when you’re a refugee, you always ‘have to have two plans’: the ideal and the more realistic. He hesitated before continuing to add detail to his picture. ‘I don’t know about the future,’ he sighed. ‘The future is very … very strange.’ (Field notes)

Arts-based approaches have become increasingly popular in socially engaged research for exploring, understanding and representing human experiences (Wang, Coemans, Siegesmund, and Hannes 2017). This paper explores the use of non-mechanical, two-dimensional visual art in particular – meaning, namely, drawing and painting – in ethnographic research with culturally and linguistically diverse populations such as displaced youth. It explores the question: what are the possibilities, challenges and responsibilities inherent in the use of creative visual communi-cation1) with this population? Drawing from my experiences of using arts-based methods in ethnographic research on the topic of young refugees’ education, the paper suggests that drawing in particular offers a number of possibilities for both researchers and participants as a tool throughout the research process – and especially in terms of communication.

By situating drawing in the process of research, this takes attention away from its role as a product: i.e. as an object for representing communities and/or evidencing observations. When embedded throughout the research process, drawing becomes not only a way of seeing and feeling, as Taussig (2011) and Causey (2017) have argued, in reference to the embodied nature of research. Instead, when considered as a means of communication throughout, the researcher can engage themselves and others in seeing-feeling-reflecting. Drawing with participants, then, offers a way to see-feel-reflect on phenomena collectively. As such, when used with critical reflection, drawing-based techniques – both as a process and product of research – have the potential to transgress physical and social borders among youth, researchers and the wider public.

In what follows, I will discuss the use of illustration for different forms of ‘creative visual communication’, via observations from my doctoral research. In terms of structure, the paper begins by providing some background on the project and setting, before walking through the methods used and some of the visual products of the research. This involves reflections on the use of creative tasks in focus group discussions, the use of field sketchbooks and the act of disseminating findings in visual formats. It concludes with overall reflections on the use of drawing in my own and similar projects, and with a call for researchers to engage an audience beyond academia in young refugees’ stories; while paying attention to their role in constructing generalised visual narratives. In doing so, it echoes Causey’s (2017: 3) call for ethnographers in particular to ‘explore visuality with more curiosity’, while adding that we must be sensitive to participants’ relationship with it.

The paper also contributes to ethical and practical methodological conversations on how to support refugee youth to tell their stories in an engaging visual manner (e.g. Lenette 2019), while paying critical attention to how their images are used. It brings psychology, education and youth studies into dialogue with anthropology, as a means of addressing two key gaps in the latter: firstly, children and young people’s participation in research; and secondly, illustration as something done by someone other than the researcher (Mitchell 2006; Johnson, Pfister, and Vindrola-Padros 2012). The aim, overall, is to prompt more discussion of how ethnographic research with ‘vulnerable’ groups such as young refugees can be made more ethical and participatory, and to examine the responsibilities inherent in attempts to do so via creative means.

The Research Project

The research project discussed in this paper is a doctoral study exploring young refugees’ educational engagement after the age of 15. It involved fieldwork in Greece’s ‘second city’, Thessaloniki, which is located in the north of the country. While I was there, I was trying to better understand the key factors shaping their engagement with post-15 education, and the role of learning in their navigation of their ‘unsettled’ conditions. This is because many young refugees are continuing to arrive, but their participation in both formal and non-formal education2) after the age of 15 remains low (Theirworld 2020; Tzoraki 2019).

I attempted to explore the stories behind these figures by a) volunteering as a teacher and assistant myself for eight months, for four different NGOs offering non-formal educational activities in Thessaloniki; b) by holding focus group discussions with young refugees, which involved drawing tasks; and c) by interviewing people close to them, such as educators, parents, social workers and cultural mediators. Ethical approval was granted by the Social Sciences and Humanities Interdivisional Research Ethics Committee at the University of Oxford. The ‘core group’ of 12 young participants – on whom this paper concentrates – were aged 15-25; were predominantly young men (9 young men, 3 young women); and identified as Kurdish, Iranian, Afghan, Syrian and Congolese (Kinshasa). This reflects the typical gender patterns of attendance in non-formal learning activities in the city. They had come to Greece during or since the ‘peak’ of the ‘refugee crisis’ in 2015, either with or without their families, and were residing in or near Thessaloniki at the time of the study. Participants were recruited via convenience and snowball sampling, with involvement in discussion groups based on willingness to participate. While they were reminded that an interpreter (of their choosing) could be invited to allow them to communicate in the language of their choice, all decided to proceed in English. For the rest of this paper, I will focus on the role of visual art – and especially drawing – not only in these focus groups, but throughout the whole research process.

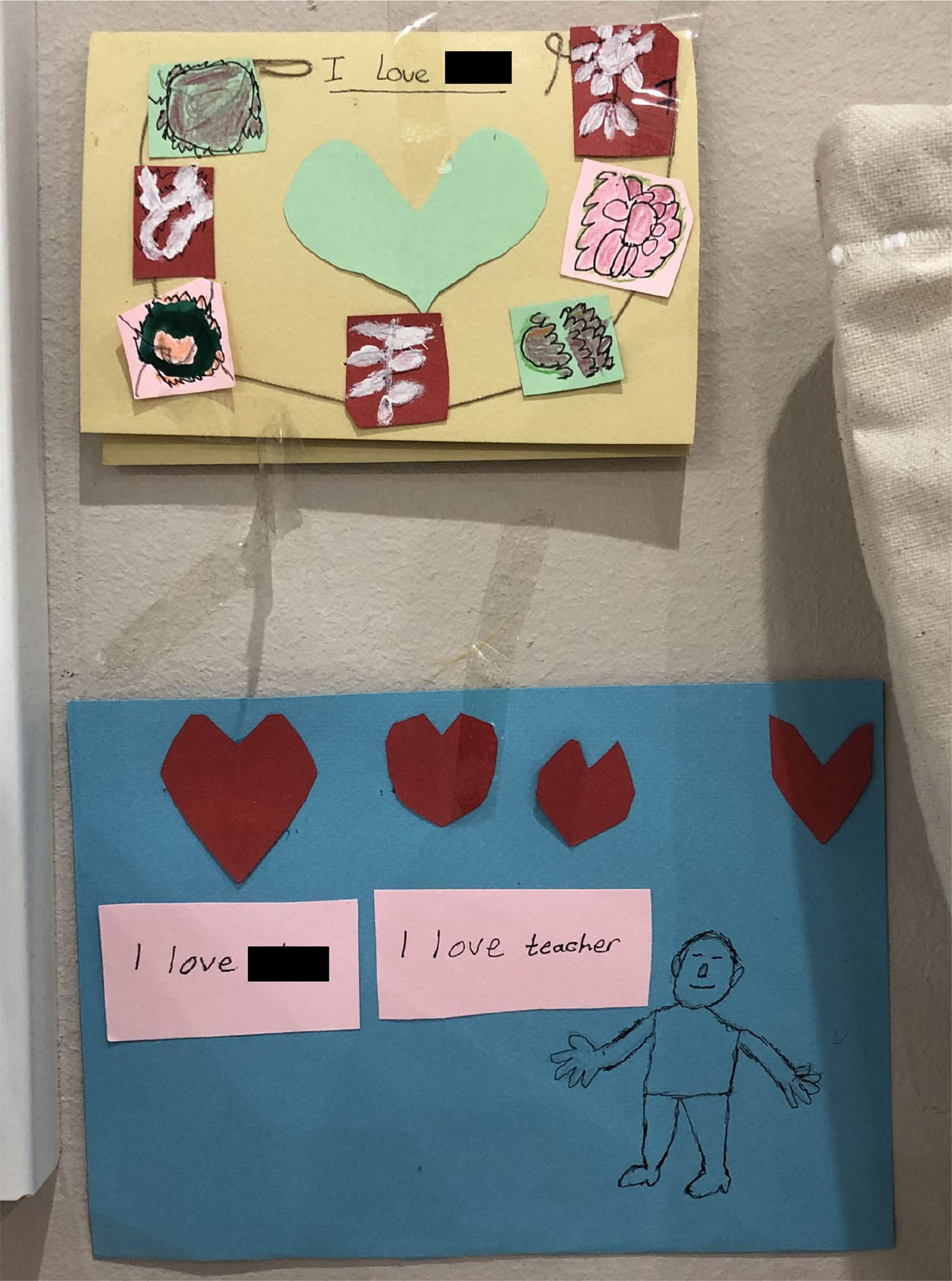

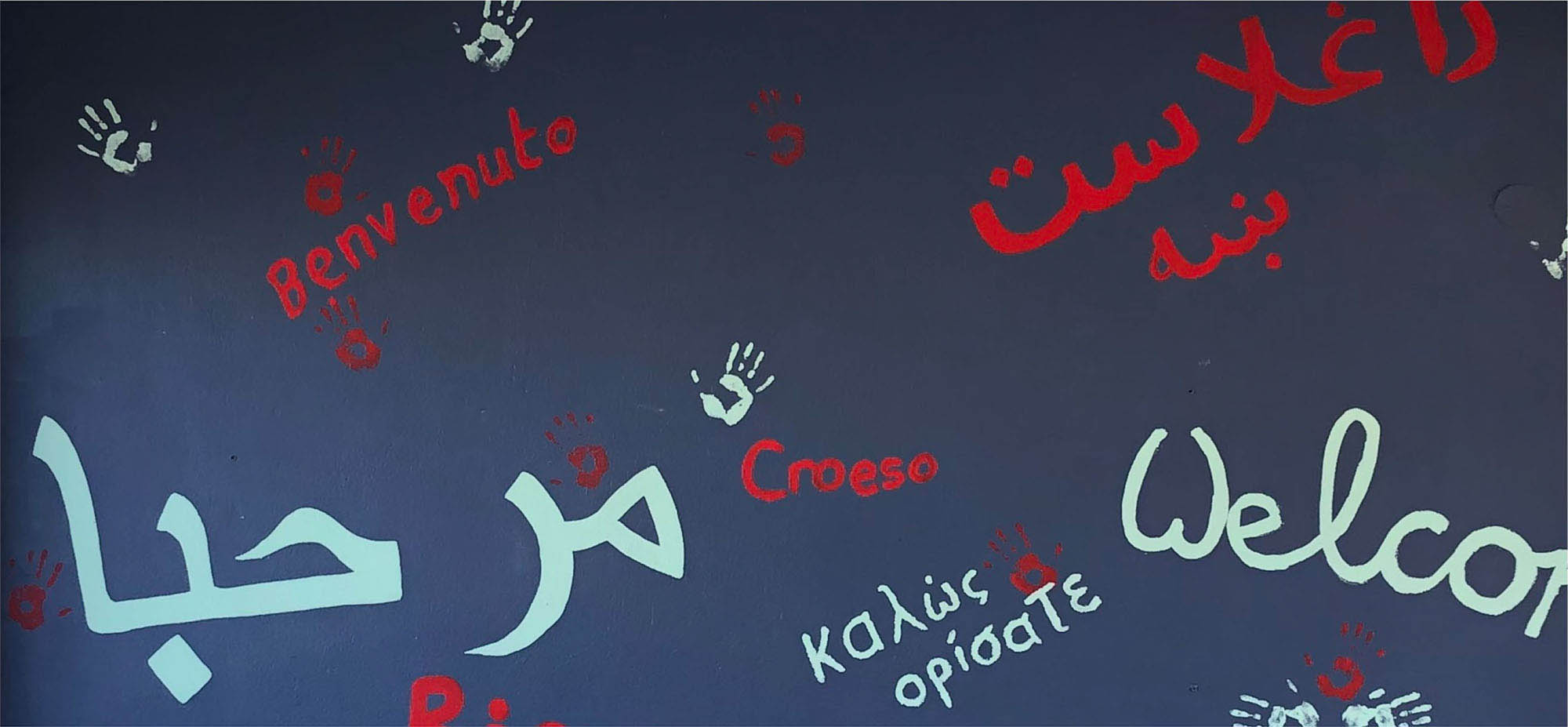

Art as Setting: Communicating Belonging

To begin with, it is worth noting that the educational settings I was involved in and observing – as a teacher, assistant and participant – were non-formal spaces characterised by creative visual communication. Community centres which serve the refugee community, and where educational activities were held, had artworks and photographs of attendees all over the walls: mostly created by members of the refugee and migrant community, and mostly communicating messages of love, hope and strength. There were often photographs of teenagers posing, ‘influencer’-style, during activities at the centres or cultural tours of the city. They were colourful places in which – unlike in public schools – young refugees could see images of themselves, or others like themselves, displayed. As can be seen in Figure 1, the walls of the different observation sites were even painted with the word ‘welcome’.

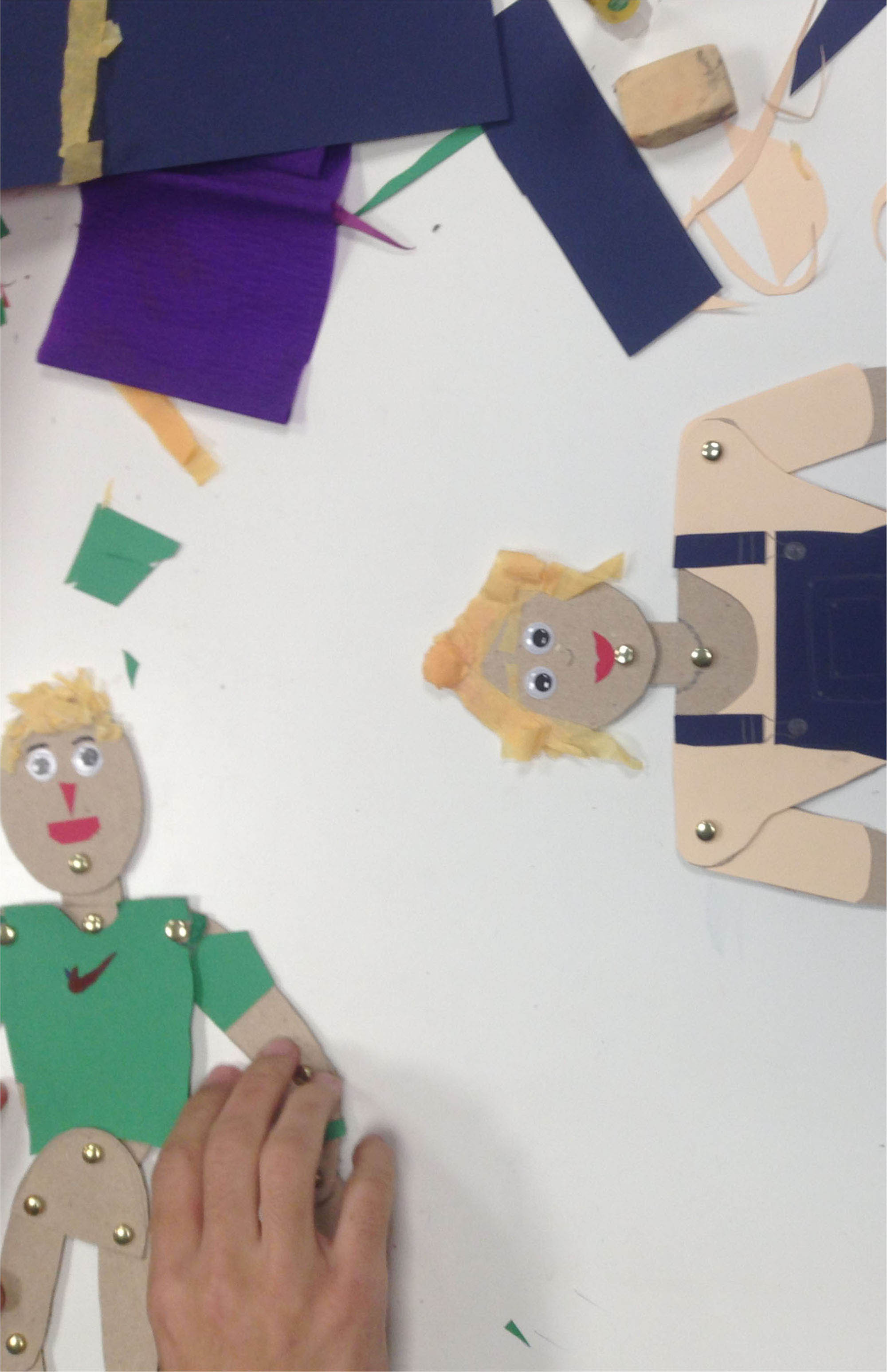

Alongside popular English and Greek language classes, various arts and crafts workshops took place in these settings, with attendees often teaching one another skills. They were common around the city of Thessaloniki and in camps outside of it, and were mostly organised and funded by local or international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and/or United Nations agencies. These courses were often run on an ad hoc basis, and some had loose age parameters (such as 15-24) or gender restrictions (as with women-only spaces). It was in these environments that I met many young people, who would often grow in confidence over the course of several weeks or months through participation in the projects. One interviewee, Alex – a coordinator of such programmes – talked about how for some, arts workshops could became spaces of escape from the ‘whole refugee thing’: a place in which youth could meet for short periods and laugh, be playful and share their interests and personalities with peers in similar situations and sympathetic facilitators. Other research has documented this potential of arts education and practices for promoting ‘valuable’ interactions among young refugees and the wider community (Hunt 2023; Korjonen-Kuusipuro and Kuusisto 2019).

It was in these types of spaces that I met many young refugees, as I was volunteering as a language teacher and assisting with other learning offers. As these young people were familiar with the concept of collaborative, group-based creative activities, such as those shown in Figure 1 – and also with interacting via visual art – I decided to carry this over into the group interviews, as we will see below.

Drawing as Process: Enabling Communication

Researchers working with children and young people – and indeed, those seeking to employ more participatory methods with all age groups – have increasingly been incorporating creative visual methods such as drawing into their research processes. The use of images and image-making in modern social science can be said to have roots in psychology and visual anthropology. However, in the case of psychology, images may be analysed following the exercise without explanatory input from youth, which produces a risk of misinterpretation (Thomas and Jolley 1998). According to Literat (2013: 85), the roots of image-making in visual anthropology are equally problematic: involving traditionally anti-participatory documentation of ‘exotic’ cultures which ‘historically plac[es] the disempowered human subject under the colonially-charged gaze of the researcher’. While anthropologists such as Margaret Mead did collect children’s own drawings during her work on Manus Island in the 1920s (Sokolovsky 2020), this and similar research into children’s visual culture – until the latter part of the 20th Century – tended to focus on drawings as objects of analysis in themselves, for investigating the influence of culture, environment and genetics, for example (Mitchell, 2006). A growing concern with children’s active participation and voice then led to the rise of visual co-production, mostly using newly accessible digital tools such as video and photo cameras – although young people’s drawings, too, were also combined with interviewing techniques to help them express themselves in age-appropriate ways (Literat 2013). In this project, I also used drawing in combination with talk: by organising intentionally small group interviews involving drawing tasks.

The tasks were based on the idea of visual elicitation, which ‘involves using photographs, drawings, or diagrams ... to stimulate a response’ (Prosser 2011: 484). This can provide in-depth information, reduce barriers to understanding, allow children to express themselves more fully, stimulate discussion and permit the co-construction of knowledge (Kleine, Pearson and Poveda 2016; Literat 2013; Prosser and Burke 2008). It also shifts the focus onto ‘intermediary artefacts’ (Prosser 2011: 484), meaning that participants feel less pressured to speak directly. This is especially helpful when adults are the interviewers and children the interviewees, due to differences in status and power. As young people were invited to draw during the session, it also involved active participation, making the research process more engaging for young participants (Crivello, Camfield and Woodhead 2006). Similar methods have been used in other ethnographies seeking children’s perspectives on their education (e.g. Barley and Russell 2018) and in studies exploring issues such as young refugees’ well-being (e.g. Chase, Otto, Belloni, Lems and Wernesjö 2019). The idea was to keep them drawing over the course of approximately 60-90 minutes, while we talked at the same time. In this way, the drawings and drawing tools acted as the ‘intermediary artefacts’ which mediated attention on them and avoided direct interviewing.

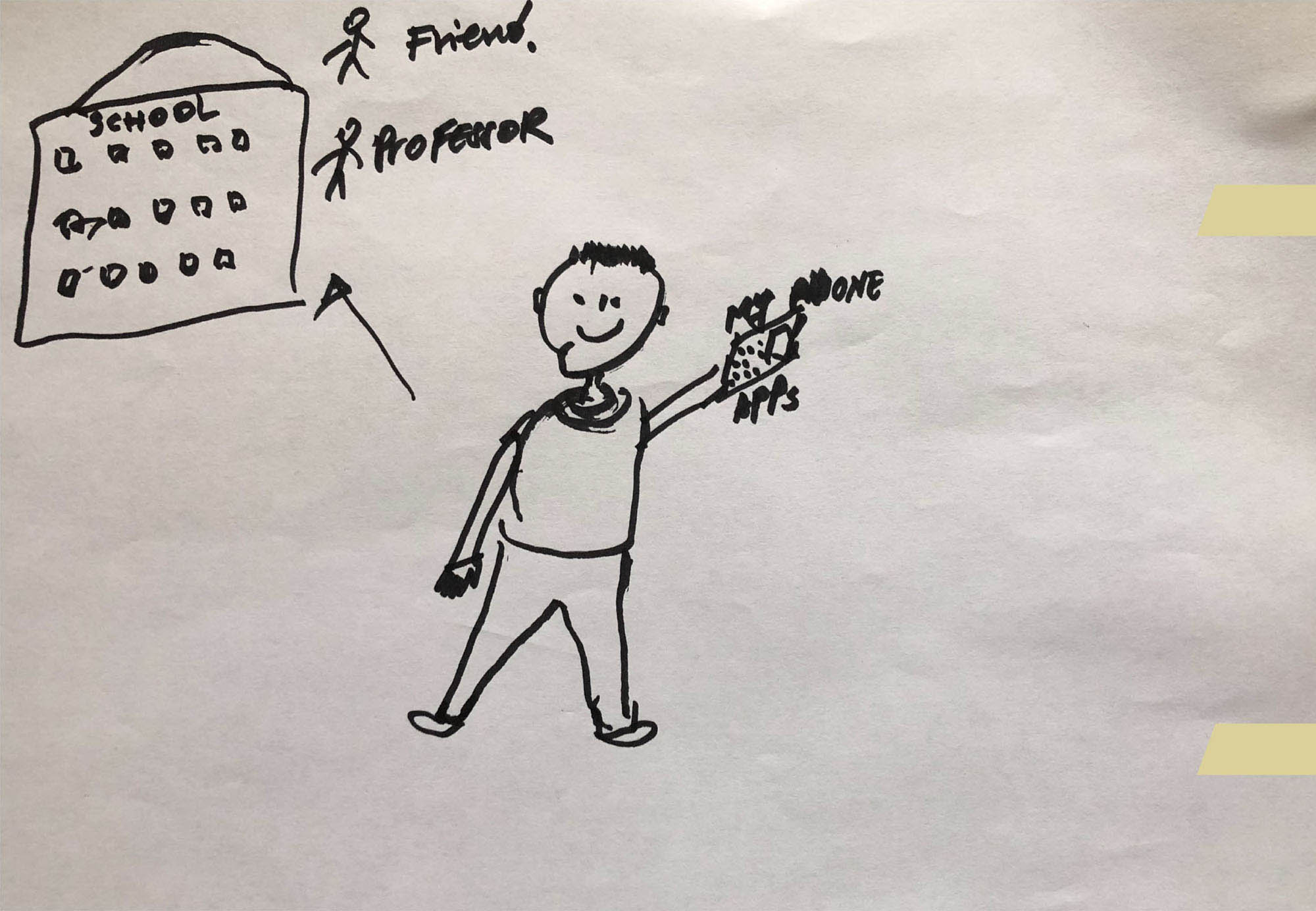

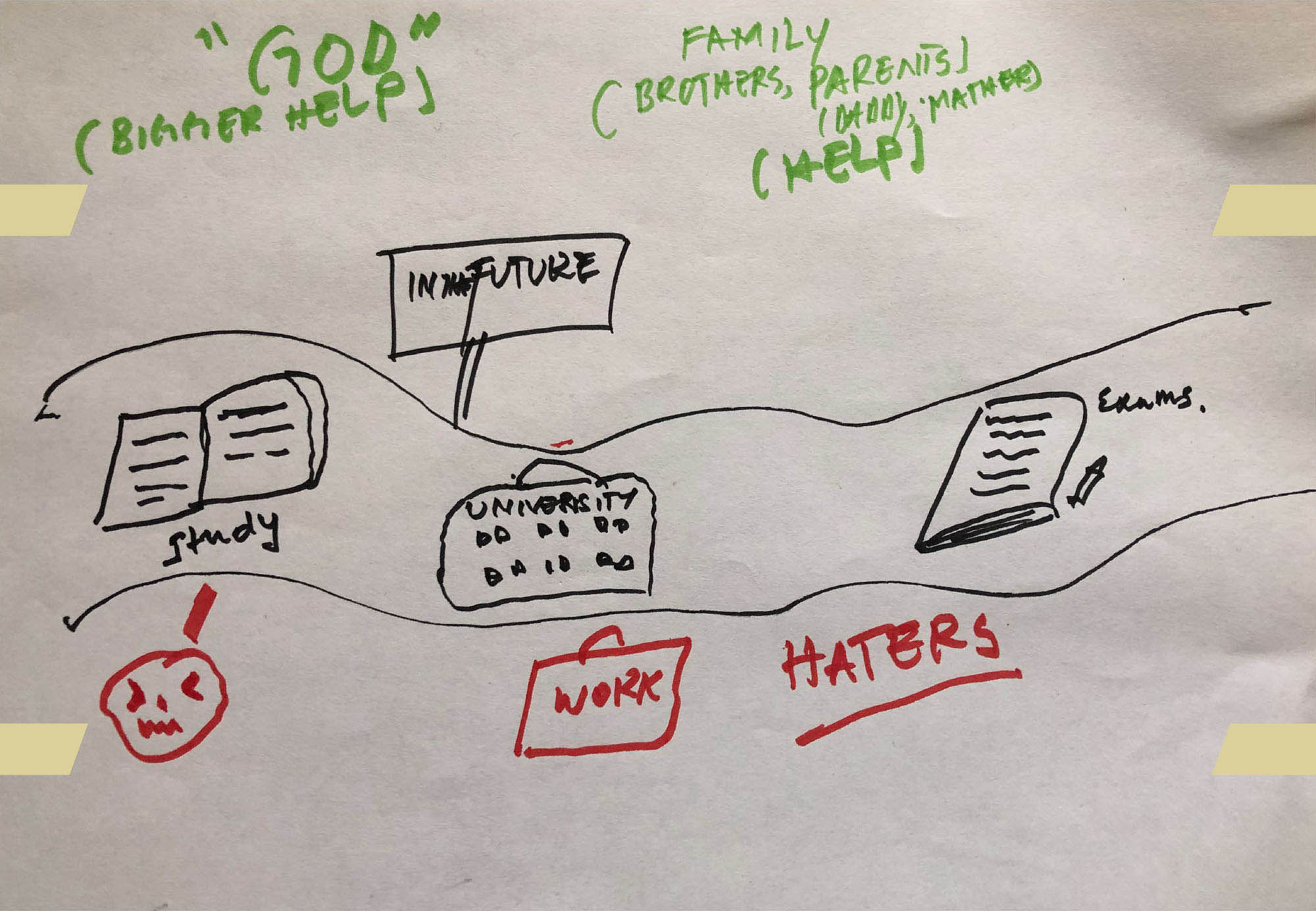

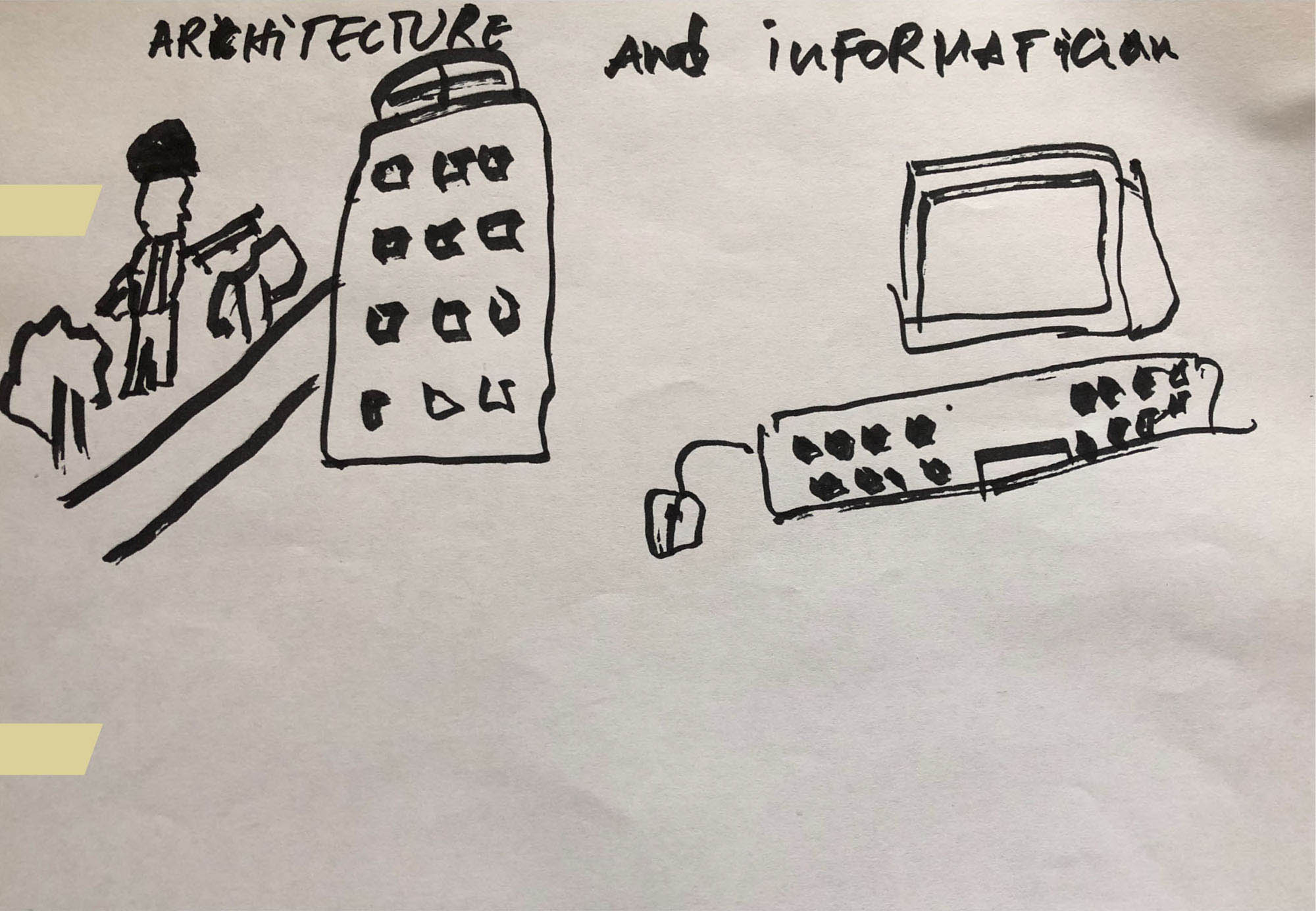

Specifically, I set three drawing tasks, and an example of how one young participant responded can be found in Figure 2. These drawings are by Fabrice3), a 16-year-old from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The first task was to draw themselves in the present, showing the places where they learnt and who they meet there. Fabrice added his school, his friends, his teachers and also mentioned his use of technology for learning. He also used labels on his picture, which were not required, but which he chose to use. The second task was to draw what they hoped they would be doing in the future, in around five years. Fabrice drew a building and a computer, which he labelled as ‘architecture’ and ‘informatician’. He chatted the whole time he was sketching: responding to my prompts, but also offering information himself, such as who his role models were, what would be ‘cool’ about being an architect, and so on.

The third and final task was to sketch out a pathway connecting the first two pictures and showing the steps to their aspired-to future, using different colours to show the supports and challenges they expected along the way. As can be seen in Figure 2, Fabrice added ‘God’ as the biggest help, and ‘haters’ as an underscored challenge. I asked him why he had underlined this, and what he meant by ‘haters’. Gradually he and his friend in the group told me that ‘haters’ meant, for example, the people who shouted racist abuse at them around the city.

When the participants had finished, we taped their pieces of paper together and discussed their drawings as a whole. As is evident in the example given here, the idea was not to have a complex or even necessarily complete artwork at the end of the session; and some participants, such as Fabrice, still used a lot of text. The focus was instead on fostering a drawing-enabled process of communication.

Although I was only able to conduct a few of these sessions before COVID-19 restrictions were put in place, I came away with several observations and reflections on using this technique. In terms of the possibilities of drawing, I found that it gave those who were more reticent to speak in an additional language – or reticent to speak at all – a lower-stakes way to gradually engage in interactions and build their confidence. Changing the task three times also slowly got them warmed up to discussing the more difficult challenges. The paper and colouring pens – as simple, low-cost intermediary objects – mediated and prompted talk among everyone present, which made the whole experience more relaxed and even playful. Other researchers have noted similar benefits of creative group activities, in which attention is refracted onto everyone present (Literat 2013; Trell and van Hoven 2010). In addition, I found that drawing also gave them time to reflect more deeply on their spoken responses than in a ‘traditional’ interview. This is what Stavropoulou (2019: 95) describes as offering ‘time and space to consciously engage with their experiences and invest in their creativity and storytelling capacities’, to ‘render their worldviews visible’.

Another observation, which has also been noted by researchers such as Literat (2013), is that what was omitted from the drawings – as well as what was included – could be significant. For example, Fabrice did not include the arts workshops he occasionally attended in his first image. When I asked about this, he said he did not really think of it as a ‘learning place’, like school; instead, for him, it was just where he went to hang out with his friends from the refugee community and try out new skills which sounded interesting. Therefore, by asking about what was absent, I learnt more about the meaning he attached to these different learning spaces.

In terms of considerations for using creative visual methods again in the future, the first thing I learnt is the need to be flexible: for example, having extra activities or instructions prepared if participants finish quickly, lose interest or tell you that they do not particularly like drawing. This latter point cannot be assumed one way or the other, whatever age they are. Some of the older participants enjoyed drawing more than their younger peers; and on one occasion, a teenager asked if he could just write instead of drawing anything at all. I told him that he could use the pens and paper however he wished, and so he talked continuously while making written notes on his paper. His hesitance was due to feeling unskilled in drawing – and the limited timeframe did not give us a chance to work on his confidence by exploring introductory techniques such as building up simple shapes. Moreover, the intention was not to build artistic competence, but rather to communicate perspectives about the research topic alongside shared mark-making – whatever form this took.

The second lesson is that I believe it helps if the researcher can be truly ‘present’ at the table with the young participants. If you doodle along with them and laugh at your own pictures, it helps to build rapport and avoids them feeling as though they are under a microscope. Literat (2013: 89) agrees that drawing, as a non-mechanical technique, can go some way to levelling the power imbalances between the adult researcher and young participants, given that ‘the children are in their own element’. Related to this, the third lesson is not to be too prescriptive: to follow their lead and focus on being present and actively listening, rather than being preoccupied with gaining specific data. While the practical and ethical parameters of a study – and indeed, one’s funder’s priorities – may dictate particular questions, those questions may not relate to the most pressing issues youth wish to talk about. Therefore, it is important to allow space and time for participants’ thoughts and jokes – not only to foster rapport, but also to be more youth- (or indeed participant-) centred. Other researchers have also emphasised the need to ensure time for one-on-one exchanges, clarifications, exploring similar and different perspectives and welcoming children’s jokes and stories in group discussions more generally, while also covering all necessary topics (Hennessy and Heary 2005; Litosseliti 2003).

The fourth lesson is to pay attention to the symbolism of any particular elements used in instructions or a model. My initial plan was to ask participants to draw a river to their future. However, while sharing the idea with a colleague, I was warned that rivers could potentially be associated with death in some cultures. As such, it is preferable not to make any assumptions of neutrality and keep the task more open. Similarly, regarding interpretation, the fifth and final lesson is to avoid interpreting images afterwards without youth present, as several other researchers have warned against (e.g. Trell and van Hoven 2010).

Drawing as Product: Reflecting and Communicating with a Wider Audience

Beyond the visual methods used in the focus group discussions, ‘creative visual communication’ also became entangled in the project in other ways. This is because as well as the young participants’ drawings, I also left the field with my own sketches and illustrations.

Researchers’ drawings are, of course, nothing new in anthropology, and particularly not in its social, cultural and visual forms. Even back in the 16th Century, Mexica scribes were graphically documenting the Americas for the Florentine Codex, for example (Sokolovsky 2020). However, following the advent of photography in the 19th Century – and its offer of a new, mechanised technique for recording ethnographic data – illustration took on a different role (Joseph 2015; Soukup 2014). For Taussig (2011), its role today is to provide an alternative and unique way of witnessing reality which photography cannot; what both he and Joseph (2015) call a ‘different way of seeing’. For Soukup (2014), drawing is more subjective in nature, due to its reliance on the researcher’s skills and personality – thus mirroring their psyche. In this way, for Taussig (2011: xi), drawings are not a way of reproducing reality, but of feeling it; with the drawing becoming a testimony that one saw, felt and heard that reality. In addition, they combine ‘observation with reverie’ and allow the creator to externalise impactful scenes. As Judit Ferencz suggests (Holsgens 2018), illustration also works on a different temporality: with the drawer marking the mundane alongside historical moments, and thus allowing for an intermingling of the two. All of these observations have contributed to, or stem from, a (re)new(ed) interest in ‘graphic anthropology’ in the social sciences, architecture and beyond (e.g. Causey 2017; Haapio-Kirk 2022; Ingold 2011; Lucas 2020).

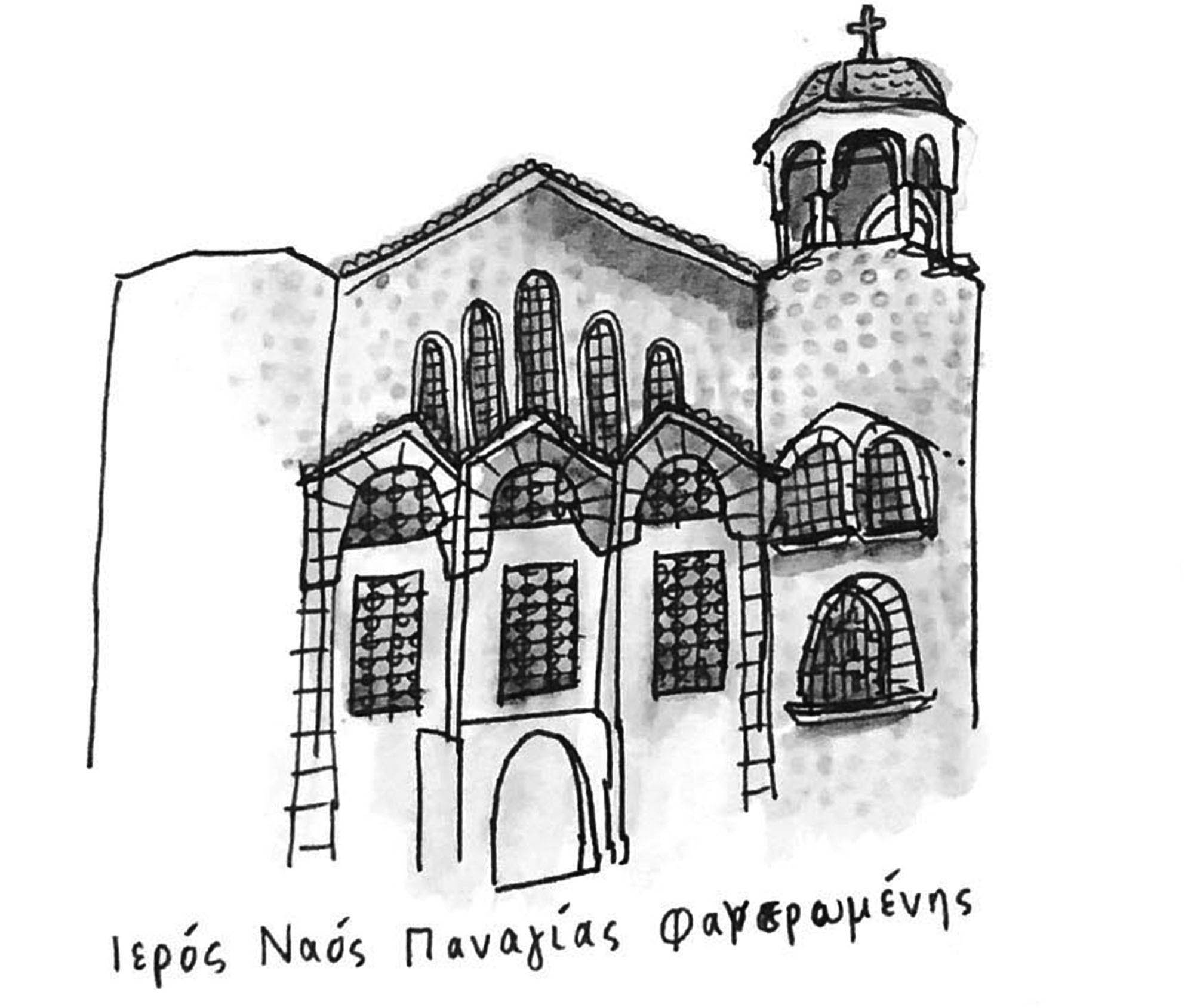

I found drawing very useful for not only reflecting on what had been communicated by participants, but also for communicating to my future self and a wider audience the key things that I had been seeing, hearing and feeling. In the examples from my notebooks provided in Figure 3, it can be seen that I captured what were, for me, ‘critical incidents’ as a researcher: those context-specific, ‘unplanned, unanticipated, and uncontrolled’ moments which have a ‘profound effect’ (Webster and Mertova 2007: 77). One example, shown in Figure 3, involves bumping into a young refugee on the street – a teenager I had met in various learning spaces – who told me that he was planning to leave the country via irregular means. This sketch enabled me to make this interaction material: to externalise and isolate it, and to take time to consider the implications of his words as I drew, rather than scribbling quick notes. Apart from such interactions, I also sketched mundane, everyday scenes, aspects of the physical environment, social maps and some reflections on my position in the field. I could not capture all of this with a camera – especially as I worked with young people, and photography raises ethical concerns.

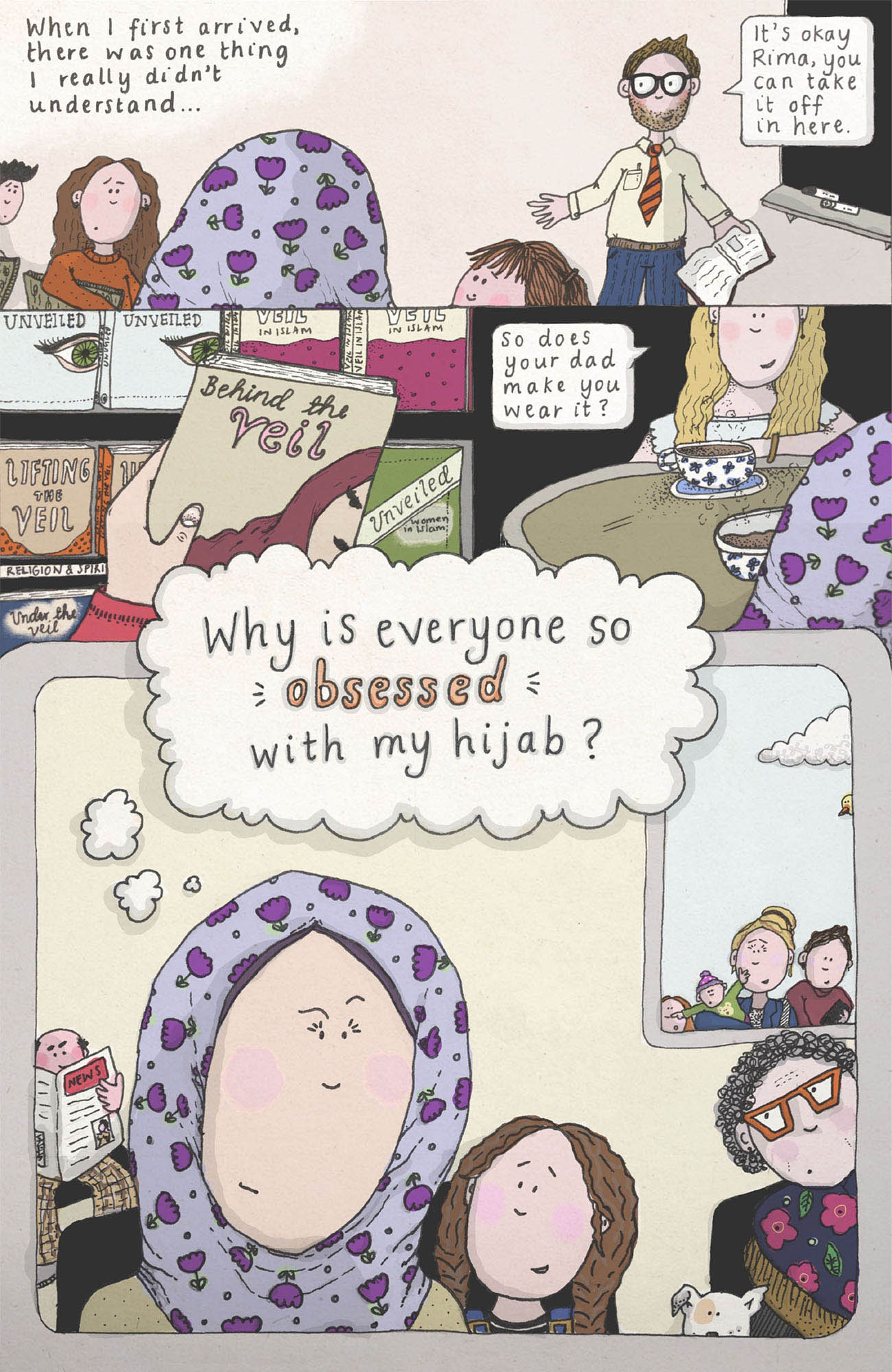

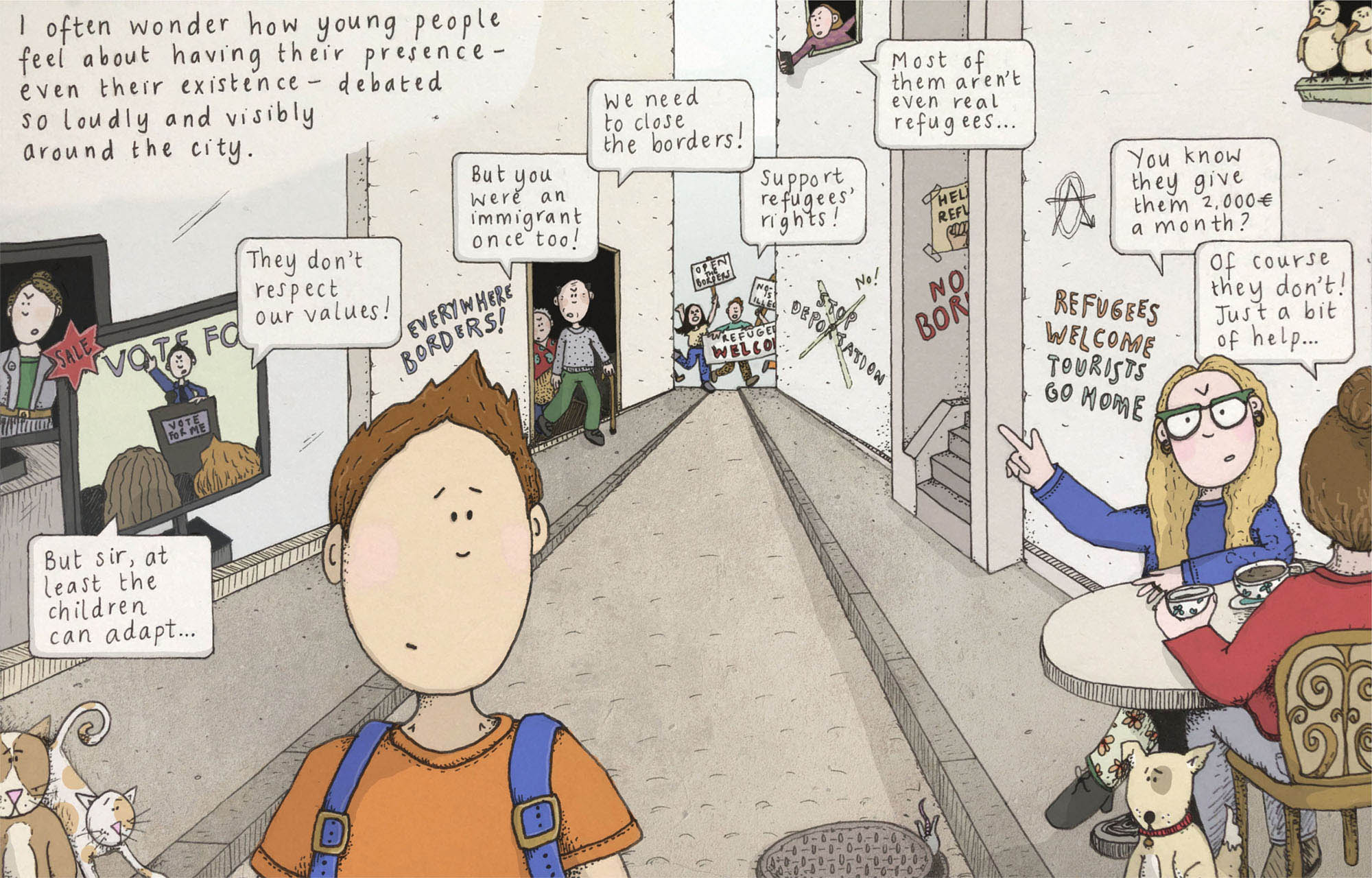

The final way in which visual art came into the project is related to this: in the development of some of the sketches from my notebooks into comics (see Figure 4). I found that this allowed me to boil down a large ethnographic mass of ideas, thoughts, feelings and meanings into single, essential ideas, which allowed me to communicate them to a wider audience in what Sou (2019) suggests is a more accessible, inclusive way. The first comic summarises what several girls told me about their experiences of wearing the hijab – and the unwanted attention it brought – which was combined with findings from the wider literature on this topic. The second also explores the idea of ‘hypervisibility’, as well as invisibility, and is also told from a young person’s perspective. The third demonstrates the discursive web in which young refugees are entangled, which is fraught with constant reminders that their presence in a European country is a controversy. These images have been shown at academic and practitioner-focused conferences, and also included in a recent exhibition in the UK entitled Illustrating Anthropology – discussed in a dedicated special issue of Trajectoria (Haapio-Kirk 2022). This had both online and offline iterations, with the physical version taking place in Liverpool city centre, UK (see Figure 5). This, I believe, allowed some of the young people’s perspectives from my study to be communicated to a wider public beyond the academy, without the issues of privacy, anonymity and misappropriation which are associated with photography. In being awarded a monetary prize as part of a ‘Migration and Mobility’ art competition, one illustration has also had a direct impact on participants: in providing financial support for a camp-based educational initiative run by a young refugee in Greece.

Figure 5 Illustrating Anthropology exhibition in Liverpool, November 2020, with the author’s work highlighted (©Open Eye Gallery)

Figure 5 Illustrating Anthropology exhibition in Liverpool, November 2020, with the author’s work highlighted (©Open Eye Gallery)

However, this approach does, of course, have drawbacks. Firstly, the works shown here are my interpretation of young people’s perspectives. Secondly, passers-by in Liverpool may not be the key decision-makers who, arguably, should be targeted, as those who need to better understand the views of newly arrived populations in Europe. Thirdly, there is a danger with creating and sharing any images of young refugees that they may be misinterpreted or feed into generalised visual narratives about this community. As the ‘refugee reception crisis’ in Europe is already highly visual – due to 24/7 media coverage, potentially patronising fundraising campaigns and photos being used as propaganda (Topali 2020) – we need to be very careful about any images we create which add to these visual narratives. This is the main reason why I opted for the comic format: as it involves both images and some explanatory text. However, in future research, it would be preferable to work much more closely with youth to create visual products with them during the research process, based around their most pressing concerns. This criticism was recently made by Sian and Nugent (2019: 2), who warn that often, art products are most often researcher-led, and not co-created – meaning that the researcher ‘translates’ findings into arts-based formats. For them, this is due to researchers having too few guidelines on how to manage the collaboration process.

Conclusions

To summarise, this paper has explored the potential and challenges of drawing as a communicative device in ethnographic research with young refugees. I would like to finish by reiterating the benefits of creating images with youth, rather than of or even for them, and of engaging with drawing as a tool throughout the research process – and not just at distinct moments. Overall, it is a low-cost, accessible and inclusive technique for communicating with youth and with oneself as a researcher, and potentially also with a wider audience. In terms of its impact, while video storytelling, for example, has been found to reduce negative attitudes towards refugees and immigrants (Audette, Horowitz and Michelitch, 2020), comics – as a form of hand-marked witness – have been described by Davies (2022: 187) as ‘particularly adept at reconstructing the human rights of dehumanized populations, and facilitating a borderless solidarity’. As such, we can say that illustration has the potential to transgress multiple social and spatial borders, and to invite both participants and audiences to ‘see-feel-reflect’ together. However, on the part of the researcher – as with everything in life – critical reflection, as well as playfulness, are key.

Acknowledgements

This article draws from a doctoral project funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, United Kingdom.

Notes

- 1)

- ‘Creative visual communication’ refers here to the process of creating visual art (collectively) for a communicative purpose; whether between young people, between youth and their educators, between youth and the researcher or between youth/the researcher and a wider audience.

- 2)

- The Council of Europe (2019) defines formal education as that which takes place in educational systems, follows a syllabus and involves assessments; while non-formal education (NFE) – despite also being organised and intentional – mostly takes place outside of the formal system and does not lead to accreditation. It may be more focused on particular activities, skills or areas of knowledge and take place in community settings such as NGOs.

- 3)

- Participant’s name pseudonymised.

References

- Audette, N., J. Horowitz and K. Michelitch

- 2020

- Personal Narratives Reduce Negative Attitudes toward Refugees and Immigrant Outgroups: Evidence from Kenya. Working Paper. Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions. Nashville: Vanderbilt University.

- Barley, R. and L. Russell

- 2018

- Participatory Visual Methods: Exploring Young People’s Identities, Hopes and Feelings. Ethnography and Education 14(2): 223-241.

- Causey, A.

- 2017

- Drawn to See: Using Line Drawing as an Ethnographic Method. Ontario: University of Toronto Press.

- Chase, E., L. Otto, M. Belloni, A. Lems and U. Wernesjö

- 2019

- Methodological Innovations, Reflections and Dilemmas: The Hidden Sides of Research with Migrant Young People Classified as Unaccompanied Minors. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 46(2): 457-473.

- Crivello, G., L. Camfield, and M. Woodhead

- 2009

- How Can Children Tell Us About Their Wellbeing? Exploring the Potential of Participatory Research Approaches Within Young Lives. Social Indicators Research 90(1): 51-72.

- Davies, D.

- 2020

- Crossing Borders, Bridging Boundaries: Reconstructing the Rights of the Refugee in Comics. In E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh (ed.) Refuge in a Moving World: Tracing Refugee and Migrant Journeys Across Disciplines, pp. 177-192. London: UCL Press.

- Haapio-Kirk, L.

- 2022

- Ethno-Graphic Collaborations: Crossing Borders with Multimodal Illustration. Trajectoria 3.

- Hennessy, E. and C. Heary

- 2005

- Exploring Children’s Views Through Focus Groups. In S. Greene and D. Hogan (eds.), Researching Children’s Experience: Approaches and Methods. London: SAGE.

- Hunt, L.

- 2023

- Creative (En)Counterspaces: Engineering Valuable Contact for Young Refugees via Solidarity Arts Workshops in Thessaloniki, Greece. Migration Studies.

- Ingold, T. (ed.)

- 2011

- Redrawing Anthropology: Materials, Movements, Lines. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Johnson, G. A., A. E. Pfister, and C. Vindrola-Padros

- 2012

- Drawings, Photos, and Performances: Using Visual Methods with Children. Visual Anthropology Review 28(2): 164-178.

- Joseph, C.

- 2015

- Illustrating the Anthropological Text: Drawings and Photographs in Franz Boas’ “The Social Organization” and the Secret Societies of The Kwakiutl Indians (1897). In A. Lardinois, S. Levie, H. Hoeken and C. Lüthy (eds.), Texts, Transmissions, Receptions: Modern Approaches to Narratives. Leiden: Brill.

- Kleine, D., G. Pearson, and S. Poveda

- 2016

- Participatory Methods: Engaging Children’s Voices and Experiences in Research. London: Global Kids Online.

- Korjonen-Kuusipuro, K. and A.-K. Kuusisto

- 2019

- Socio-Material Belonging – Perspectives for the Intercultural Lives of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors in Finland. Journal of Intercultural Studies 40(4): 363-382.

- Lenette, C.

- 2019

- Arts-Based Methods in Refugee Research: Creating Sanctuary. Singapore: Springer.

- Literat, I.

- 2013

- ‘A Pencil for Your Thoughts’: Participatory Drawing as a Visual Research Method with Children and Youth. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 12(1): 84-98.

- Litosseliti, L.

- 2003

- Using Focus Groups in Research. London: Continuum.

- Lucas, R.

- 2020

- Drawing Parallels: Knowledge Production in Axonometric, Isometric and Oblique Drawings. London: Routledge.

- Mitchell, L. M.

- 2006

- Child-Centred? Thinking Critically About Children’s Drawings as a Visual Research Method. Visual Anthropology Review 22: 60-73.

- Prosser, J.

- 2011

- Visual Methodology: Toward a More Seeing Approach. In N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research 4: 479-496. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Prosser, J. and C. Burke

- 2008

- Image-Based Educational Research: Childlike Perspectives. In J. G. Knowles and A. L. Cole (eds.), Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Sokolovsky, J.

- 2020

- Drawing in the History of Anthropology and its Place in Visual Anthropology. Presentation at the EASA Conference 2020.

- Soukup, M.

- 2014

- Photography and Drawing in Anthropology. Slovak Ethnology 4(62): 534-546.

- Stavropoulou, N.

- 2019

- Understanding the ‘Bigger Picture’: Lessons Learned from Participatory Visual Arts-Based Research with Individuals Seeking Asylum in the United Kingdom. Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture 10(1): 95-118.

- Taussig, M.

- 2011

- I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Thomas, G. V. and R. P. Jolley

- 1998

- Drawing Conclusions: A Re-Examination of Empirical and Conceptual Bases for Psychological Evaluation of Children from Their Drawings. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 37(2): 127-139.

- Topali, P.

- 2020

- Visual Regimes of Mobility Photographic Exhibitions on Refugees during the Financial Crisis in Greece. Visual Anthropology Review 36(2): 319-342.

- Trell, E. M. and B. Van Hoven

- 2010

- Making Sense of Place: Exploring Creative and (Inter)Active Research Methods with Young People. Fennia 188(1): 91-104.

- Tzoraki, O.

- 2019

- A Descriptive Study of the Schooling and Higher Education Reforms in Response to the Refugees’ Influx into Greece. Social Sciences 8(3): 72-85.

- Wang, Q., S. Coemans, R. Siegesmund, and K. Hannes

- 2017

- Arts-Based Methods in Socially Engaged Research Practice: A Classification Framework. Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal 2(2): 5-39.

- Webster, L. and P. Mertova

- 2007

- Using Narrative Inquiry as a Research Method: An Introduction to Using Critical Event Narrative Analysis in Research on Learning and Teaching. New York, NY: Routledge.

Websites

- Holsgens, S,

- 2018

- Sketching Visual Anthropology: An Interview with Illustrator Judit Ferencz. Society for Cultural Anthropology. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/sketching-visual-anthropology-an-interview-with-illustrator-judit-ferencz (accessed September 13, 2023)

- Sian, G. and M. Nugent

- 2019

- Towards Identifying Best Practice Guidance for Science Researchers When Considering Working with Artists on Public Engagement Projects. National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement. https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-08/science_research_engagement_and_the_arts.pdf (accessed September 13, 2023)

- Sou, G.

- 2019

- Four Reasons to Graphically Illustrate Your Research. LSE Impact Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2019/05/24/four-reasons-to-graphically-illustrate-your-research/ (accessed September 13, 2023)

- Theirworld

- 2020

- Finding Solutions to Greece’s Refugee Education Crisis. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/RefugeeEducation-Report-240420-2.pdf (accessed September 13, 2023)

Contact

Lucy Hunt

*Replace “■” with “@”.