There is a gap on my i-phone camera of twenty months, between November 2019 to June 2021, when, for the first time in many years, I took no photographs. This ellipsis corresponds to the first period of lockdown, when in British Columbia, we abandoned and closed our schools, leisure facilities and workplaces and transferred our real-life presences online while quarantining ourselves in our homes. It was also during this time that we heard the shocking news of the discovery in Kamloops, in northern British Columbia, of 215 unmarked graves of Indigenous children who fell victim to the Canadian residential school system – the first of many that, as we had long been forewarned, would trickle into our conscience.

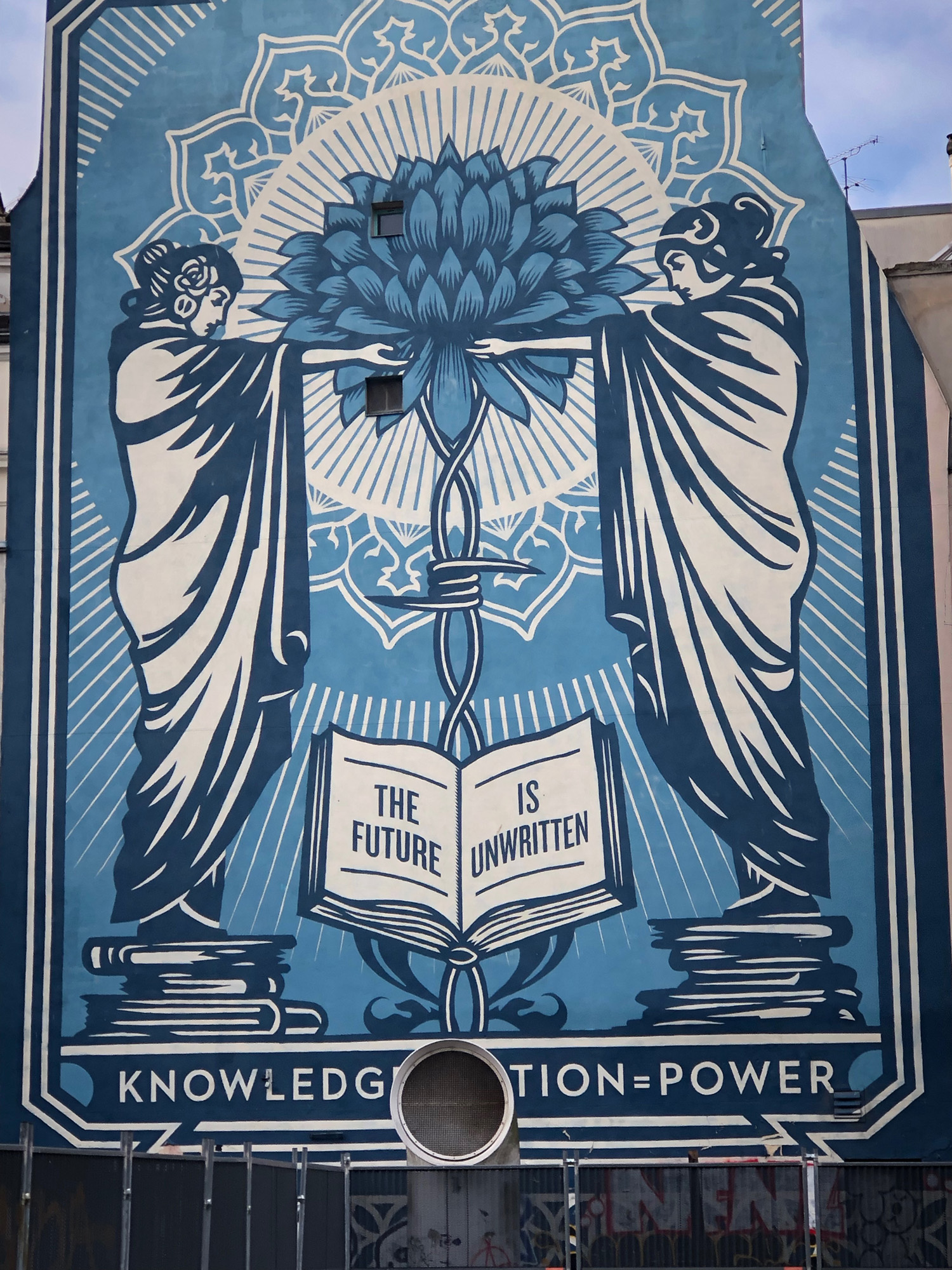

“The Future is Unwritten”: A Year of Living in the Pandemic

(Published March 31, 2023)

Initially during this period, we could only leave the place where we lived to run essential errands like weekly shopping forays and urgent trips to the pharmacy; later, government authorities encouraged us to take walks in Vancouver’s parks or along the sea-wall as long as we were masked and observed two meter’s distance between ourselves and others. Any other walkers unable to repress an involuntary cough or violating our newly extended social spaces immediately filled us with trepidation as physical relations became fraught with dangers at the same time that new online associations began to flourish. The bleakness and cold of winter combined with the emptiness of the city and periodic product shortages created a dark and melancholy atmosphere in which neighbors, alone or huddled together in their apartments experienced not dissimilar seldom iterated fears and insecurities. Small groups of anti-vaxxers sporadically picketed traffic, loudly demonstrated outside hospital wards filled with the sick, and brazenly threatened nurses, doctors and other hospital workers. From our sixth-floor apartment by the Burrard Bridge, overlooking the looming glass apartment buildings with their invisible inhabitants surrounded by empty waterway, every twenty or so minutes we heard ambulance sirens, doubtlessly ferrying another COVID victim to St Paul’s Hospital across the shore. Avidly and repeatedly, we checked the internet news channels for some glimmer of relief, but found only more dreadful statistics of the virus’s spread and devastation across the globe. With few exceptions, the words and faces of the US’s then inane government and its supporters, cynically promoting hatred against China or dispersing conspiracy theories against Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director-general of the World Health Organization, and Dr Anthony Fauci, medical advisor to the US president, sickened us and revealed that after all, malice and evil do exist.

After the first few weeks of isolation, a spontaneous cacophony of pot banging erupted and filled the air at 7:00pm every evening from the balconies of the high-rise apartments surrounding us – our way of showing our appreciation to health-care workers and first responders. It gradually became less loud and was then abandoned after six or so months leaving nothing to puncture the homogenous days in which work and family life had melded into one another, having become the prey, like so many later things to our collective exhaustion. We will all remember, couped up in small apartments, the dull, weekly ritual of our children taking online classes via Microsoft Teams, while parents continued their workplace meetings, planning and development activities on Zoom and other platforms after desperately searching their closeted quarters for space and quietude. At first, we felt elated that we could continue to work and grow after transforming our physical presences into digital projections; later we grew fatigued by remote working, and after that we became despondent by the drain on our creativity and spontaneity and the slow erosion of identity and meaning our workplaces had once unknowingly given us. This essay is not, however, about the first year of the pandemic but its second stage, between June 2021 to September 2022, when, with the success of the most comprehensive vaccination program ever undertaken, falling fatality rates, declining incidence of infection and encroaching bureaucratic safeguards over travel, movement and public and commercial spaces, lockdown rules were slowly and cautiously relaxed, releasing us, no one knows for how long, from our physical bondage. Fear and anxiety nevertheless remained, exacerbated by government warnings, changing travel advisories, threats of financial sanctions, and forced quarantine procedures. As I write this essay, the world has lost between 6.5 to 9 million of its inhabitants and from the news from China, Russia and elsewhere, the pandemic is far from over.

The second half of COVID restrictions in British Columbia largely coincided with my sabbatical leave (July, 2021- July, 2022) from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. This was a fragmented and disconnected time like, to coin a phrase from Kurt Vonnegut, a “timequake”; universities and museums continued to withhold bursaries and grants to visiting researchers; conferences and fieldwork in most parts of the world were prohibited; museum collections were closed and physical relationships and meetings were only slowly and nervously beginning to return. It was a period when life resumed only under highly restrictive, often changing rules and regulations, with limitations on access to public institutions, the imposition of hygiene protocols governing masking, washing, cleaning, and touching, the reluctance of some to return to their work premises, and the lingering fear of others to venture outside their homes.

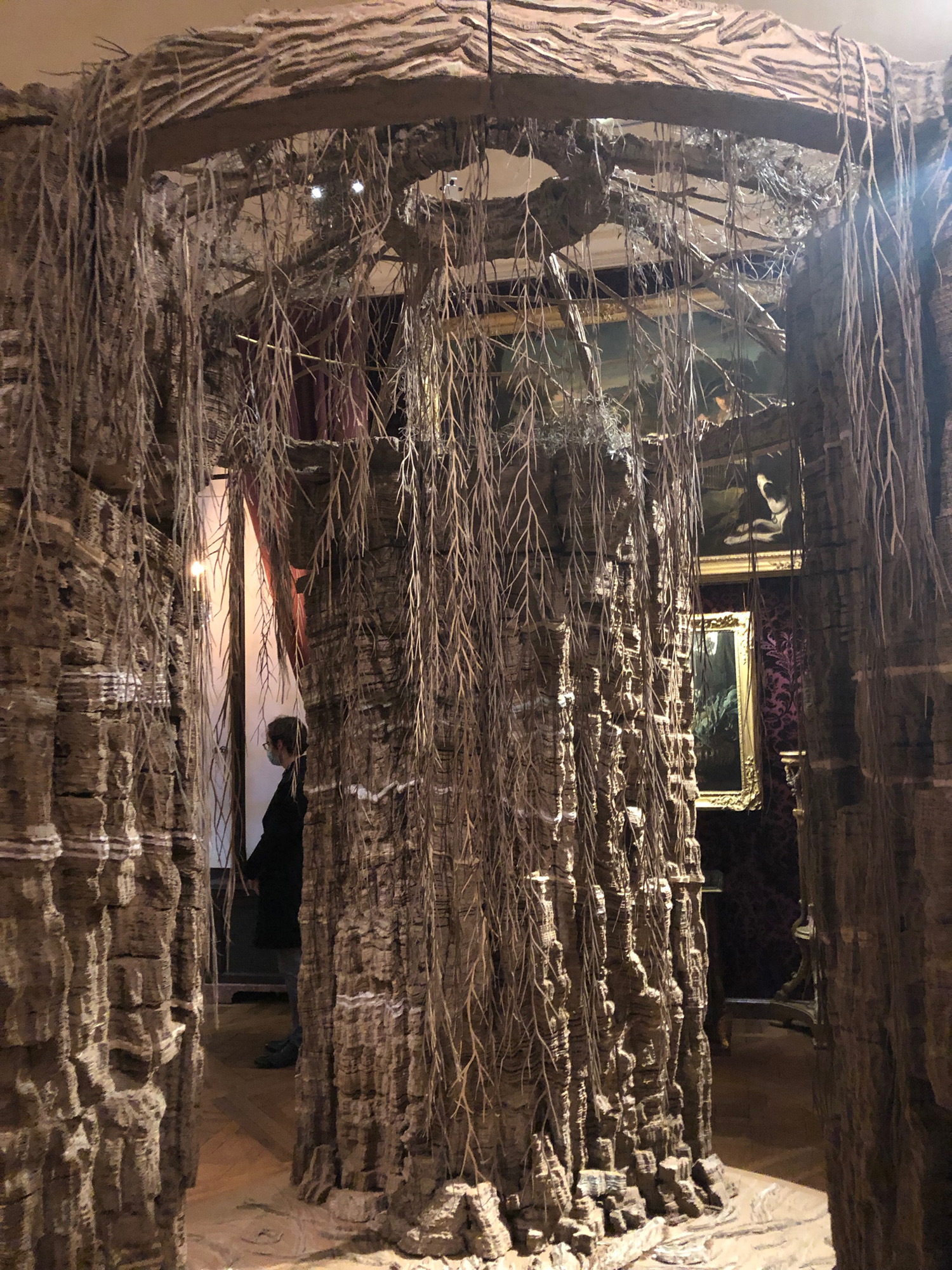

Personally, I felt disappointed that I had wasted much of the year because of my repeated failure in North and South America to find a host institution for my sabbatical year. Nevertheless, because of quarantine and travel regulations, I had completed and published two books ahead of the year in which I had planned to finish them. This though only caused me more consternation because I was left with no fresh research projects to begin work on. By the end of my sabbatical, I had written and submitted two articles and an exhibition review essay and co-organized an international workshop, but this still seemed inconsequential, especially, after I had spent most of the summer of 2021 gardening at our island house just outside of Vancouver. After finishing my garden work, my wife, the museologist and curator Nicky Levell, suggested I write a book on the things I and her had collected during our life, not for publication, but to give to each of our three children. I wrote two volumes, A Short History of Things I and II, which led to a memoir, A Life in Full, which contained the overflow of my memories and likewise was intended only for our children. Still unhappy with myself, I dismissed these as indulgencies and still insufficient to justify my year’s research leave. Beginning in November, I began again to travel, visiting Paris twice in the next eleven months, making three journeys to Portugal and one to England, as well as twice spending time in Mexico, Colombia and of course in British Columbia. A few days before the end of my sabbatical, on my return flight from Europe to Vancouver, I was idly looking through the i-phone photographs of my past year when I suddenly realized that throughout this time I had been working, unknown to myself, on a completely unarticulated project, which you now see set out before you; “The Future is Unwritten. A Year of Living in the Pandemic”. Wry, melancholic, ironic, funny, sad, I have selected 35 images out of about 800 to evoke my experience of the world in which I moved during these usually lonely journeys. Often, the images picture people-less or barely populated interiors and cityscapes; many were taken in newly reopened museums; some capture cleaners and repairmen preparing for the world’s reopening, while others document accidental ironic juxtapositions of images and signs, or the lonely imprints of human habitation and the slow return of public life in the world’s great cities and institutions. By the summer of 2022, despite the threat of the escalation of the war in Europe, famine, the beginning of global inflation and recession, medical fears over new strains of COVID, the spread of Monkeypox and the worsening climate crises, the world’s air-fleets had once again become full of returning tourists; the streets of its great cities had refilled with people, and hotels had dramatically increased their room costs in response to the excessive demands of exasperated newly emboldened visitors. Two days after I returned to my office in the Dorothy Somerset Studio at the University of British Columbia, I glanced the rows of easels that had been stored since 2019 next to two plastic skeletons, which forms the final image in this diary. In some ways, we humans are the same as we were three years ago, but we are also different. Accelerated by optimism over the current fall in COVID cases, the feeling of crises, anxiety and impending doom, peddled by disaster and horror movies as well as by the leaders of the world’s nuclear armed countries, have tipped us into a dizzying celebration of excess which again, like three years ago, we continue to use to mask the existential predicaments that threaten us even more.