In Zambia, poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facilities are responsible for frequent diarrhoeal disease outbreaks which usually originate from peri-urban settlements. Previous research assessing the factors that impact peri-urban WASH revealed that top-down public policies had a minimal impact on communities, partly because of limited community engagement in WASH initiatives. Overall, our study aimed to co-create a model for child-youth engagement in peri-urban WASH through participatory action research, considering diverse actors and sociocultural influences. This paper focuses on the use of visualisation as a participatory research tool to create an inclusive co-creation environment.

Our research was part of ‘Dziko Langa’, a child-youth club founded in 2017 focused on assessing and enhancing peri-urban WASH to promote better health and quality of life. Our participants used photovoice and art to assess WASH conditions, identify areas for intervention, and conduct intervention activities in their communities. Participants incorporated additional visualisation methods, including clay for art, drama, dance, poetry, and songs into the co-creation process. Digital storytelling aided participants in reflecting on their club activities and setting future WASH goals.

In all these cases, visualisation fostered communication and engagement among participants and the broader community. This reframed personal daily life struggles into communal challenges that could be collaboratively addressed. In addition to reporting the participants’ findings and activities, our paper reviews how the peri-urban communities in Lusaka, Zambia acquired and processed WASH information and knowledge through visualisation methods. Gaining insight into their unique perspectives and interpretation of reality provides an opportunity to reassess the development of programs and campaigns focused on improving WASH.

Key Words WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene), visualization, peri-urban Zambia, child-youth engagement, participatory action research

“I See You” – Tackling Peri-Urban Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene by Employing Visualisation Strategies with Children and Youth in Lusaka, Zambia

(Published March 27, 2024)

Abstract

Introduction

Inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions contribute significantly to faecal-oral contamination diseases, including diarrhoea, cholera, and typhoid; and effective WASH access is crucial for preventing pathogen transmission through controlling faecal ingestion, safe faecal management, and proper handwashing (Kumar, Maurya and Saxena 2020). Addressing this issue is a global priority, currently guided by Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6: clean water and sanitation (WHO 2018).

Zambia, a low-middle-income country in sub-Saharan Africa, faces formidable challenges in providing safe water and sanitation. National data shows that 67.7% of the population has access to improved drinking water, while only 40% have access to improved sanitation facilities (CSO 2016, WHO and UNICEF 2017). The situation is even direr in peri-urban areas, where roughly 56% lack access to safe water, and up to 90% lack proper sanitation facilities (Republic of Zambia 2006). Inadequate WASH conditions have been linked to recurring cholera outbreaks in Zambia, often originating in rural fishing villages and peri-urban settlements (WHO Global Task Force on Cholera Control 2011). Lusaka, the capital city, houses around 70% of its residents in peri-urban areas (CSO 2012). These 37 peri-urban settlements are particularly affected by insufficient WASH conditions and healthcare services. In the 2017/2018 rainy season, a cholera outbreak in peri-urban Lusaka led to 5,905 registered suspected cases, primarily within Lusaka (91.7%), and it spread to seven out of 10 Zambian provinces (Kapata et al. 2018). The primary cause of this outbreak was faecal contamination of food and water (Kapata et al. 2018).

Efforts are underway to improve WASH and related health conditions. However, when viewed from a Zambian sociocultural lens, improved WASH often aligns with Western practices that may not fit local customs. For example, the use of sitting toilets instead of squatting toilets and private facilities instead of shared ones, which are more common in Zambia’s communal society, can lead to cultural mismatches. Economic and environmental barriers also influence the choice between large-scale WASH infrastructure and small-scale decentralized solutions (Nyambe and Yamauchi 2021; Nyambe, Agestika and Yamauchi 2020). Consequently, many WASH programs are top-down and aid-driven, lacking principles of co-creation, co-design, and collaboration in community engagement efforts. Hence, exploring ways to harmonize cultural practices with effective faecal transmission prevention is crucial.

Our research investigated WASH in peri-urban Lusaka, Zambia, with a specific focus on involving non-professional local actors, notably children and youth, through the Dziko Langa (DL) club. Considering the unique context of peri-urban Lusaka, our research emphasized visual assessment and interventions for peri-urban WASH, aiming to develop an empowering bottom-up approach to enhance local WASH conditions. This article introduces the key stakeholders, outlines the visual methods employed, and presents our observations and findings regarding the role of visualization in the research process.

Methodology

Research Sites

Before commencing the official research, nine peri-urban settlements in Lusaka were assessed between August and October 2016. Further preliminary research was conducted in three of the nine settlements and two were selected as primary research sites for the overall study. For further information on the preliminary WASH assessment of the study area, please refer to Nyambe et al. (2018).

Research Design: The Dziko Langa Club

To conduct research with children and youth in the research sites, the Sanitation Project research team (Yamauchi and Nyambe) established a club to encompass the research activities. The official project counterpart in Zambia was the Integrated Water Resource Management Centre, University of Zambia (UNZA-IWRM), which signed an official MoU with the research project. The development of the club was discussed and agreed upon by the Zambian-based research team, consisting of seven Zambians under the age of 35, categorised as youths under the Zambian constitution. Note that Zambia has a youthful population, with approximately 65% of the population under 25, and a significant proportion of household heads falling within the 18–29 age bracket (CSO 2016). The Zambian-based research team included Nyambe, Hanyika, four youth facilitators living in the research sites (all members of the Zambia Scouts Association), and two youth coordinators acting as mentors who supported the facilitators (one of them being a member of the Zambia Scouts Association). The team (assembled by Nyambe) participated in preliminary data collection and local community discussions about WASH management in the nine peri-urban settlements, as previously mentioned. The name of the club, Dziko Langa (DL) meaning ‘My Community/Country’ in the local lingua (Nyanja language), and its slogan, Tigwilizane meaning ‘Working together’ were chosen by the team of youth. (Hanyika 2019a) Hanyika, a local videographer, developed the DL logo.

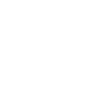

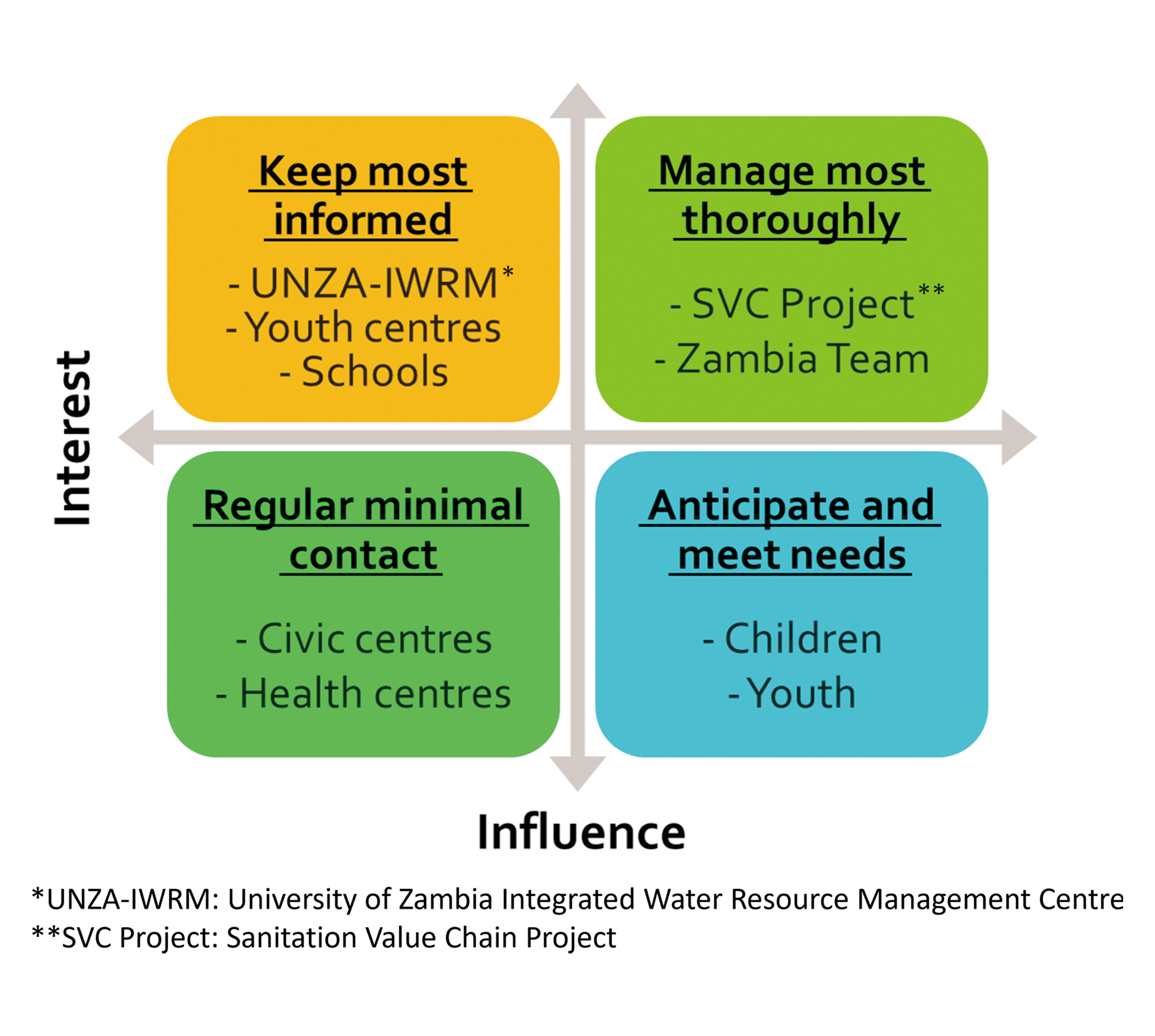

The research project was introduced to schools, youth centres, and gatekeepers at the research sites under the name DL in August 2017. Figure 1 illustrates the stakeholder analysis of the project at its inception, indicating the key stakeholders. The DL was introduced to the research sites as a new club and research project seeking children and youth volunteers interested in community WASH. Children and youth DL members were recruited as co-researchers and frontrunners of WASH in their peri-urban communities through participatory action research (PAR). Action Research can be defined as “a process of systematic inquiry that seeks to improve social issues affecting the lives of everyday people” (Hine 2013: 151). The evolving research method consists of repeated cycles of problem identification, planning, action, observation, and reflection, enabling individuals and groups in action research to make necessary changes for social improvement (Figure 2). Through PAR, participatory research methods can be incorporated into research activities for the active involvement of non-professional actors (children and youth). The initial goal was to develop a bottom-up approach to community assessment and intervention in peri-urban WASH, despite the research team’s focus. Thus, the PAR process allowed for changes over the research period.

Figure 1 Stakeholder Analysis categorized according to Interest and Influence

Figure 1 Stakeholder Analysis categorized according to Interest and Influence

Figure 2 Five-stage Participatory Action Research Cycle

Figure 2 Five-stage Participatory Action Research Cycle

Participants

The DL members included children (10–14 years old) and youth (18–24 years old) from two peri-urban settlements in Lusaka. Before COVID-19, DL had approximately 80 children and 40 youth members. Participation was voluntary and informed consent was obtained from the participants and their parents (for child participants). Ethical approval was obtained from the ERES Converge Ethical Approval Board, Lusaka (Ref. No. 2017-Mar-012) and the Faculty of Health Sciences, Hokkaido University, Japan (Ref. No. 16-103).

The DL members were trained on research methods and data collection primarily by Nyambe, and local professionals (Environmental Health Technicians from the local hospitals at the two research sites and youth workers). Parents, school authorities, and youth centre leaders were informed about the research activities but were not involved in data collection or analysis. These individuals, along with the broader community, were invited at the point of result sharing by children and youth, who primarily used visual means to present their findings.

Research Methods

In participatory research, visualisation refers to the use of visual tools and techniques to represent and communicate information, ideas, and findings. Visualisations can be presented in various forms, including maps, diagrams, photographs, videos, or other visual representations. They are used to make complex concepts and data more accessible, facilitate dialogue, and enhance participant engagement (Meyer 2010). In our work with DL, three main participatory research methods were introduced for problem identification, including photovoice and digital storytelling (used by DL youth), and art (used by DL children) (Hanyika 2019b). Photovoice and art data collection were conducted several times during the research period, with subsequent research findings being shared with the broader community by DL members through public exhibitions. Photovoice and art findings led to additional actions and events by DL members, including community clean-ups and WASH education.

1. Photovoice and Art

Photovoice is a visual participatory research method, in which participants were given cameras and asked to take pictures to be used while telling stories of their lives and communities (Wang and Burris, 1997). Art was used in a similar manner as photovoice. Instead of taking photographs, the children were asked to draw pictures. Unlike photovoice which depends on the environment, children can draw about their personal, public, and private experiences with WASH.

In photovoice, participants were trained to use a camera effectively by a photographer. Additionally, ethical guidelines were taught during the training process, such as obtaining consent from individuals before photographing them or their property. To maintain focus and prioritise important narratives, participants were given time and photo limits. They were encouraged to freely capture images that they believed best expressed their narratives (Figure 3, left). In the art exercise, emphasis was placed on the creative process rather than the participants’ artistic skills (Figure 3, right). To create a comfortable environment, the participants were asked to scribble on paper before receiving instructions for the exercise. These strategies encouraged self-expression and enabled participants to share their perspectives visually.

Both the photovoice and Art exercises require framing questions to guide the process and capture specific themes or topics in the images. In the context of the WASH research, the framing question posed to the youth was, “What is WASH in your community?” The question was simplified for children, asking them to draw “What they want and what they don’t want in their communities”, concerning WASH. This question aimed to explore the perspectives and experiences related to WASH in their environment. DL youth were given four days to take photographs, while DL children had an opportunity to scribble and draw two to three images during the one-hour art exercise period.

Before sharing photographs and drawings with their peers, participants decided which ones to share. Over 200 photographs were captured during the first photovoice exercise. To prioritize participant preferences, DL youth were asked to select their best two images for contextualisation. The DL youths explained the photograph details, noting the key variables in the storyline. DL children shared fewer drawings (2–3 per child) and were given time to explain their artwork. They were asked to describe the context of the objects/actions drawn and whether they wanted or did not want these aspects in their communities.

2. Exhibitions and Sanitation Festival

To finalise the photovoice and art exercises, sanitation exhibitions were held at the research sites during the 2017/2018 cholera outbreak, after acquiring permission from the local health facilities and police departments (Figure 4). These public exhibitions showcased the artworks and photographs submitted by the DL team members. Attendees, including local government representatives, viewed the displayed works and listened to photo and art narratives shared by the DL members. The venues, one at a local school and the others at a local government office were selected by the DL members. DL members also incorporated elements of poetry, drama, and songs to effectively communicate WASH information. Furthermore, DL youths conducted focus group discussions involving community residents.

Figure 4 DL Sanitation Exhibition Venue (2018, photo by Samuel Hanyika)

Figure 4 DL Sanitation Exhibition Venue (2018, photo by Samuel Hanyika)

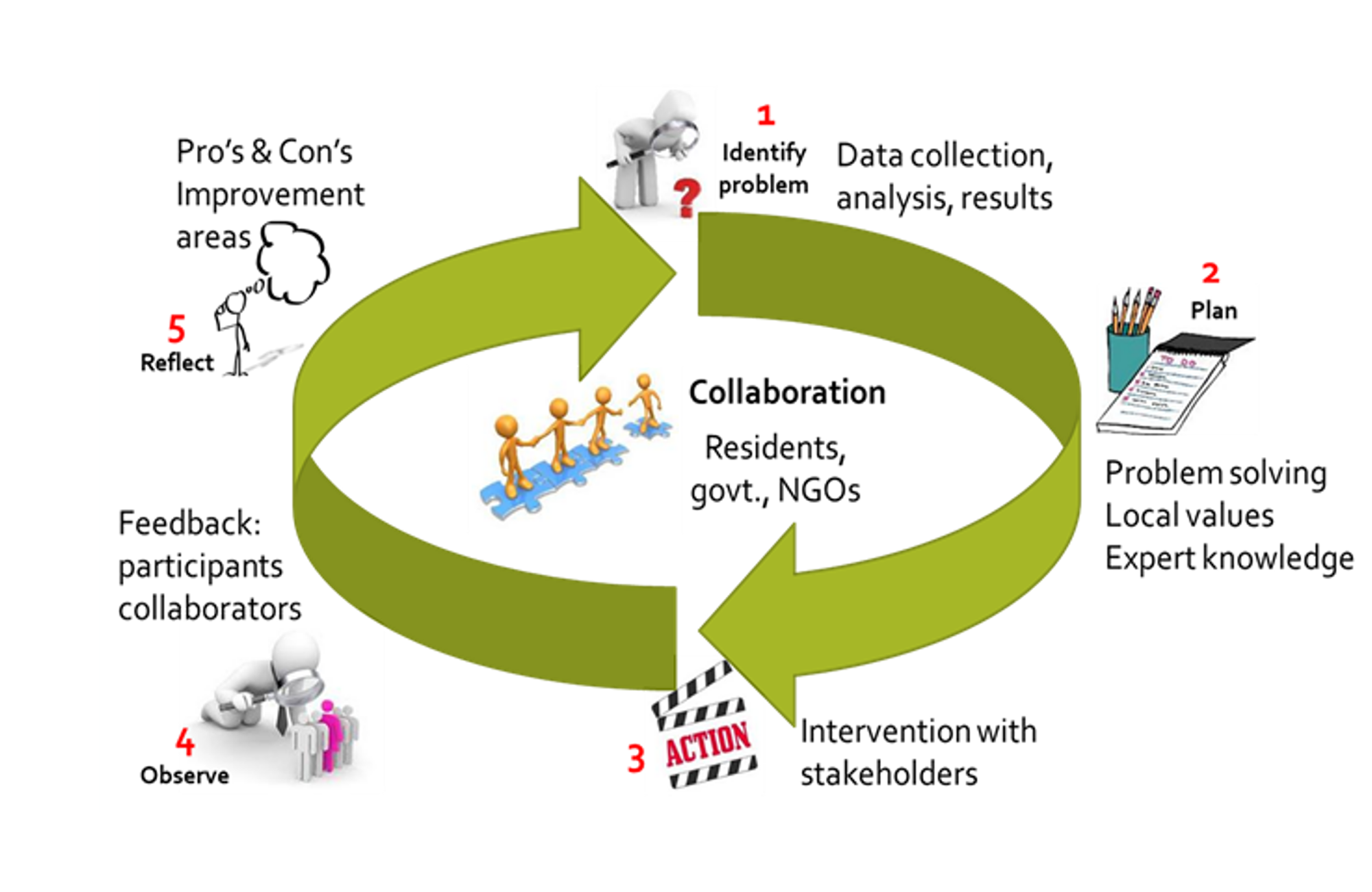

Figure 5 Dziko Langa Exhibition Booth at the Zambia Water Forum & Exhibition in Lusaka, Zambia (left: 2018, photo by Samuel Hanyika; right: 2019, photo by Yoshimi Kataoka)

Figure 5 Dziko Langa Exhibition Booth at the Zambia Water Forum & Exhibition in Lusaka, Zambia (left: 2018, photo by Samuel Hanyika; right: 2019, photo by Yoshimi Kataoka)

Figure 6 DL Sanitation Festival Day 1 (2019, photo by Samuel Hanyika)

Figure 6 DL Sanitation Festival Day 1 (2019, photo by Samuel Hanyika)

Additionally, DL members participated in the Zambia Water Forum and Exhibition (ZAWAFE) in 2018 and 2019 (Figure 5). Through this international event, the DL members had the opportunity to interact with established public, private, local, and international WASH stakeholders. In addition to setting up a small exhibition showcasing their images, DL members gave oral presentations and performed a drama for the attendees.

In 2019, the DL members held a three-day sanitation festival (Figure 6). They made invitation flyers for inviting children and youth from local schools and churches to their march past (Day 1), waste collection (Day 2), and sensitisation (Day 3) events. Day 1 incorporated the following events, including a marching band, waste collection, and clean-up of the Soweto Market, located in central Lusaka. DL members invited a local artist and health ambassador to attend their Day 2 event which involved picking up waste from one of the research sites. Additionally, DL members invited community WASH stakeholders to meet community residents for information sharing. This was coupled with a sound system that played music and quizzes to encourage community engagement.

3. Digital Storytelling

The digital storytelling workshop reviewed previous DL activities and events. It was observed that participants were constantly creating “images” of local issues and their acquired knowledge using visual methods like photovoice and art. Using a camera, DL participants captured daily life images related to WASH. These photographs represented both undesirable WASH conditions and ideal conditions they aimed to achieve. In 2019 we conducted a digital storytelling workshop, where participants reflected on previous DL activities while creating a video. Similar to photovoice and art exercises, digital storytelling involves non-experts creating short and simple videos about their lives and experiences through dialogue with others in a workshop (Ogawa 2016).

The seven participants in the digital storytelling were aged between 18 and 23 and were members of a DL media team that primarily used social networking sites to publish the club activities. They participated in almost all the DL activities since its inception and played a key role in club management. The purpose of this trial workshop was to create a video introducing DL activities on social networking sites, and all the participants decided to create a video together. The primary goal of this trial was to familiarise participants with the activity of creating videos and stories. Due to the short workshop duration, Hanyika (videographer) edited the video to overcome the differences in digital skills. To facilitate reflection on the activities, over 200 photos taken by the DL members during the photovoice were printed as cards to facilitate group work.

During the first part of the group work, DL’s past activities in chronological order were listed, totalling 22 interventions and training sessions from August 2017 to October 2019 (Table 1). Subsequently, 13 photos that made a strong impression on the participants, were selected. In the second part of the group work, the participants communicated with each other about the selected photos, the circumstances in which the photos were taken, and their thoughts about the event. Finally, the 13 selected scenes were rearranged as narratives in chronological order. The video comprised a slide show of 13 photos, and a story was written on each photo to serve as the narrative of the video, as a picture-story show (Figure 4). Eventually, the narration was recorded on the spot and the workshop concluded.

Table 1 Summary of DL Interventions as of October 2019

| No. | Activity Type | Name of Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Training and Workshops | 1. Participatory Hygiene and Sanitation Transformation (PHAST) 2. Household Survey Data Collection Training Workshop 3. Media Team Training Workshop 4. Faecal Contamination Training Workshop 5. Visualisation Workshop 6. Waste Workshop (by invitation) |

| 2 | Data collection exercises (Facilitated by DL youth) |

1. Height and Weight Measurement Exercise 2. Photovoice Fieldwork Exercise (conducted multiple times) 3. Art Exercise (conducted multiple times) |

| 3 | Clean-ups | 1. Chawama First Level Hospital 2. Keep Zambia Clean Campaign 3. World Cleanup Day (by invitation) 4. Sanitation Festival Day 1 & 2 5. Recyclable Plastic Waste Collection (by invitation) |

| 4 | WASH Education (Information sharing) |

1. Sanitation Exhibition 2. Zambia Water Forum and Exhibition (ZAWAFE) (2018, 2019) 3. Independence Day March 4. Youth Forum 5. Sanitation Festival Day 3 6. Door-to-door Waste Sorting Exercise |

| 5 | Social Enterprise (Busi-ness startup) |

1. Plastic Recycling Pilot 2. Hult Prize 2019 Competition |

Figure 7 The Process of Assigning a Story to a Picture (2019, photo by Yoshimi Kataoka)

Figure 7 The Process of Assigning a Story to a Picture (2019, photo by Yoshimi Kataoka)

Participant-derived Data Collection Methods

1. Use of Clay vs. Art Supplies and Cameras (Film 3)

Although the youth could use their mobile phones for photovoice, this was not always feasible because of mobile device limitations. Art emerged as a more cost-effective approach for data collection, albeit requiring expenditures on art supplies. However, during the exhibition, the children also created clay models to convey their experiences.

2. Drama, Poetry, Song, and Dance (Film 3)

It must be noted that while planning the Sanitation Exhibition, DL children divided themselves into groups that would prepare drama, poems, songs, and cultural dances for the event. These activities were also featured in subsequent events. They were not merely for entertainment but intended to convey vital community information and engage the audience.

3. Games and ‘Boostele’ (Film 3)

Games were primarily used during youth-to-child interactions. The youth introduced games that were commonly played in their communities as icebreakers and energisers, sometimes incorporating WASH elements. Morale chants and slogans (commonly referred to as the ‘Boostele’ in local lingua) were used similarly. The DL boostele, referred to as the ‘Dziko Langa Kilo’ was proposed by DL youth from the two research sites, who later taught it to children, guests, and event attendees. However, this has changed over time. The current DL kilo is expressed as follows:

- Participants rub their hands together (warm-up)

- One person shouts: DZIKO LANGA KILO!

- All members clap: 3 claps, 3 claps

- All members shout: A healthy living! I see you! (All members point to individuals whom the praise is directed towards)

4. Communal Discussions

During the Sanitation Exhibition, DL members from one of the two research sites discussed the various visual materials presented to attendees. The children and adults discussed separately (Figure 8).

Figure 8 DL youth discussing WASH with community members (2018, photo by Samuel Hanyika)

Figure 8 DL youth discussing WASH with community members (2018, photo by Samuel Hanyika)

5. Public Intervention Activities

DL members made use of intervention activities to encourage engagement through ‘seeing and doing’. The key activities that encouraged community engagement were waste collection, sorting, and handwashing training.

Figure 9 Door-to-door Waste Sorting Activity by DL Youth (2019, photo by Samuel Hanyika)

Figure 9 Door-to-door Waste Sorting Activity by DL Youth (2019, photo by Samuel Hanyika)

Observations, Findings, and Discussions

Numerous insights resulted, initially from the use of visualisation with the participants and later, the broader community.

Photovoice and Art

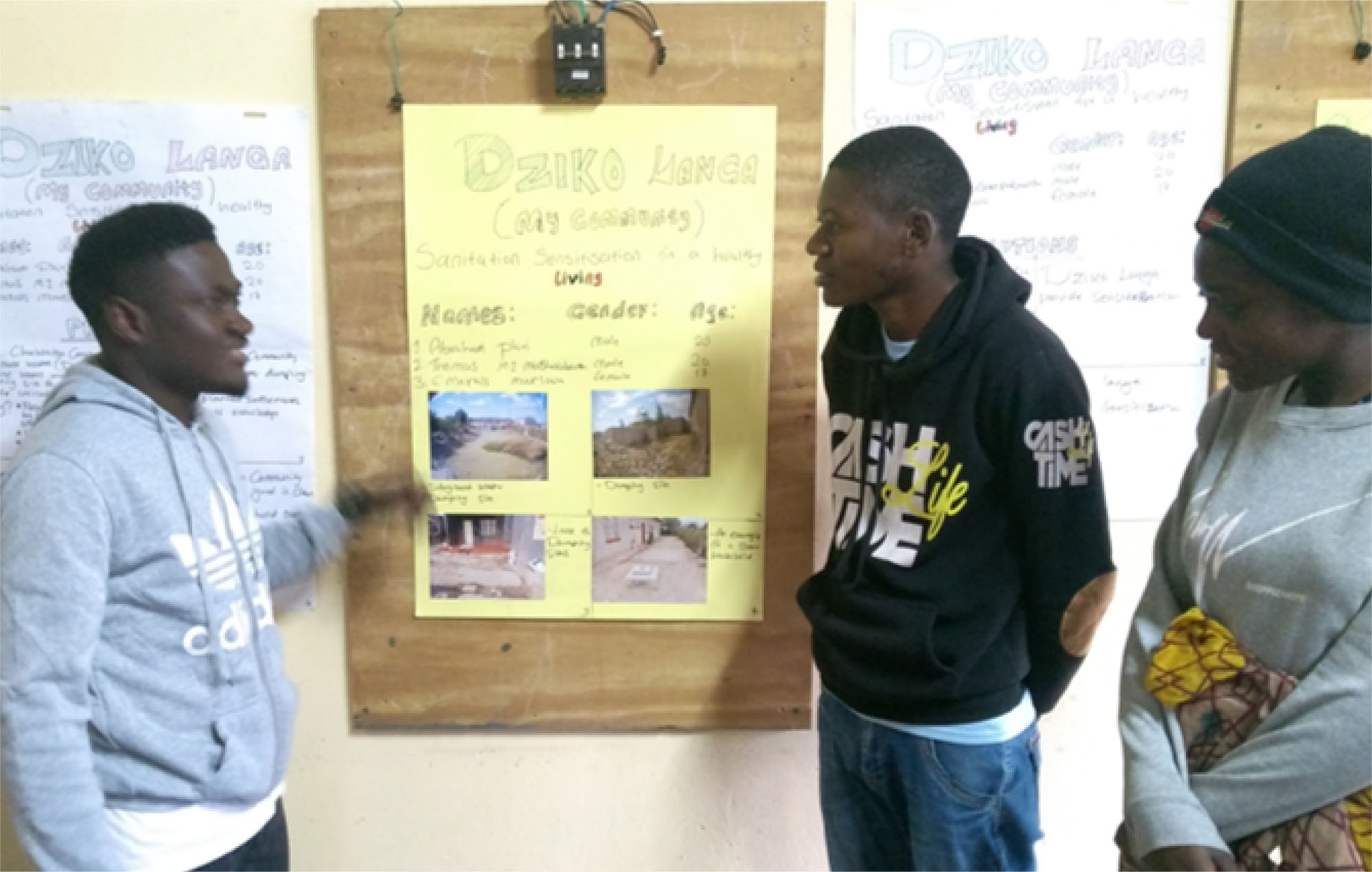

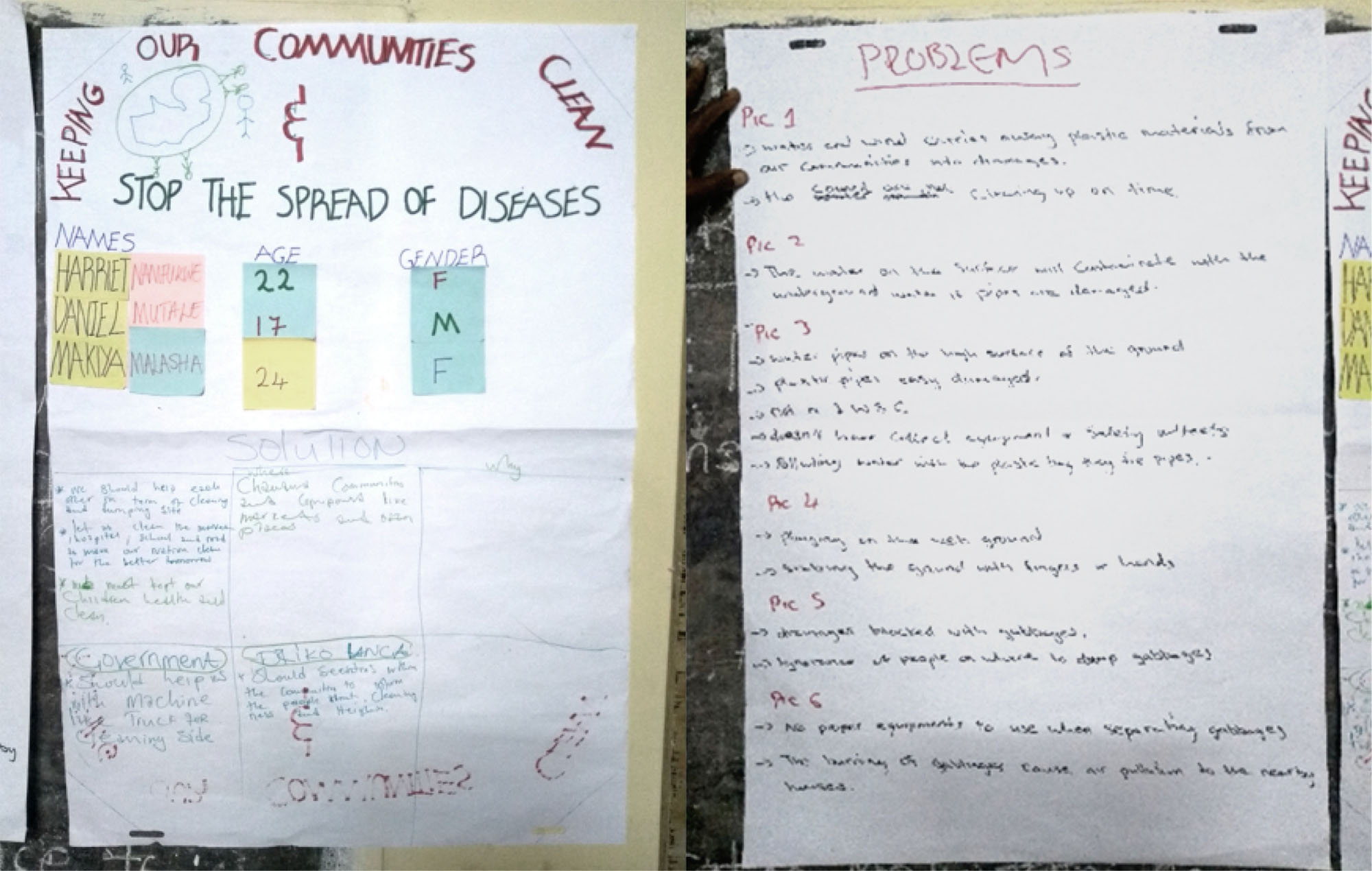

The contextualisation process led to lively focus group discussions among children and poster creation among the youth (Figure 5). The youth poster creation offered an opportunity for the basic codification of findings and further analysis of cited problems and possible solutions. Particularly, DL youth were asked to state which members of the community (DL members, community residents, and the government) could potentially solve the noted challenges. After the poster presentation, a question-and-answer session led to in-depth discussions regarding problems and solutions. The findings from the first DL photovoice and art exercises (conducted from 2017 to 2018) were published by Nyambe and Yamauchi (2021) and Nyambe et. al. (2022). Based on their photovoice and art data, including analysis and discussions, DL members (both children and youth) planned the following community interventions: (i) offering WASH education to the general community, (ii) conducting public cleanup activities in the community, and (iii) creating opportunities for the broader community to engage in WASH improvement activities. These three points led to various interventions listed in Table 1.

Figure 10 Contextualization Posters with Detailing Problems and Solutions (2018, photo by Sikopo Nyambe)

Figure 10 Contextualization Posters with Detailing Problems and Solutions (2018, photo by Sikopo Nyambe)

Exhibitions

The most attended DL events were those conducted in open spaces where curious community residents could easily participate in discussions, activities, and viewings. Visual and audio cues helped draw attendees. Once engaged, the participants and attendees were often willing to share their thoughts and feedback. During DL research, feedback was received from a wide range of participants and stakeholders. DL members participated in WASH events organised by other WASH stakeholders. Through Clean-up activities, workshops, and ZAWAFE conferences, they gathered information about the work conducted by other WASH organisations, gaining deeper insights into their activities, including what was working, what was not working, what could be done, and who could be partnered with them. These collaborative events offered spaces for DL to share WASH conditions using their cultural constructs and those of their invitees, creating an appreciation for multi-sectoral collaborations. This section highlights the feedback from various stakeholders engaged with DL and the DL members themselves.

Digital Storytelling

Digital storytelling has been treated as a method that emphasises an individual’s perspective within a group “narrative” (Ogawa 2016), with limited instances of collaborative storytelling. To overcome the difficulty of storytelling, a storytelling exercise was conducted through a DL workshop in which participants organised their previous activities chronologically and categorically using photographs, which was synonymous with playing cards. Through discussions, selections, and eliminations, all participants eventually created a single story. By breaking down the timeline and reflecting on the activities, the participants connected their activities to personal experiences. The 13 photos selected as video materials included environmental images, such as photos of public restrooms and garbage dumps taken during photovoice activities, as well as images from DL club activities. The deliverable video began with the words, “It is not everything that we need to wait for someone to do for us”, and five of the 13 photos were described as depictions of social issues in the community (Hanyika 2019d).

By describing the DL activities in ‘their own’ words, DL members became more aware of the fact that these activities were integral to ‘their own’ lives. Furthermore, by engaging in dialogue with peers who also participated in DL activities, the DL members shared their challenges as issues that the group should collectively address. The title of the deliverable video (named by DL participants), “Our Work, Our Story”, is a good indication that they perceived the issue as a collective challenge.

Finding linkages in a series of activities over a long period can be difficult. This workshop enabled participants to playfully reflect on their activities using media as aids, including the use of photographs as a card game and recording narration for the video. Using the digital storytelling method, the workshop created a process for participants to individually reflect on the organisation’s activities from their perspectives and as their actions and outputs, creating a story for the future. By connecting sanitation in their daily lives with sanitation as a problem to be solved, communication was focused towards critically rethinking local sanitation and collectively creating an image of the “sanitation we should strive for”.

Use of Clay vs. Art Supplies and Cameras

In Zambia, clay and soil play a significant role in children’s recreational activities, and they often exhibit greater comfort when using clay as opposed to paper and pencil. Clay soil, which is easily accessible and free of charge, enables children to express and recreate their lives and experiences uniquely. Previous research indicated that the choice of materials employed in activities involving young participants can significantly affect research outcomes and assessments. Serpell and Jere-Folotiya (2008) utilised clay and wire to develop a standardised intelligence test for Zambian children, who may experience discomfort when using traditional paper-and-pencil tests. The results yielded superior outcomes compared to Western intelligence tests. Future endeavours should aim to explore the use of clay as a means of modelling participants’ living environments and sharing their life experiences.

Drama, Poetry, Song, and Dance

The use of drama allowed for interactive exchanges among participants. The dialogue between the characters highlighted issues related to WASH and waste management among diverse stakeholders, adding a range of emotions to problems and solutions. This sociocultural approach facilitated discussions on community norms and behaviours. The use of drama aligns with the principles of theatre for development, which aims to foster social transformation and community empowerment through participatory and interactive theatrical practices (Boal 1992).

Like drama, poetry, and songs serve as creative means of conveying important messages. As in Zambia, the arts have long been embedded in African culture as powerful tools for information sharing, exploration, and learning. Traditional forms of artistic expression such as storytelling, music, dance, and visual arts have served as vital means of communication and knowledge transmission (Bunn, Kalinga, Mtema, Abdulla, DIllip, Lwanda, Mtenga, Sharp, Strachan, and Gray, 2020; Tuwe 2016). These art forms carry rich narratives, values, and historical insights that have been passed through generations as cultural heritage. For instance, storytelling is not only a form of entertainment but also a means of preserving cultural heritage and sharing important lessons and wisdom (Wachege and Rũgendo 2017). Similarly, traditional dances and music often convey societal messages, rituals, and historical events, providing a platform for collective learning and social cohesion (Kjørholt, Matafwali, and Mofu 2019; Mtonga 1988). These cultural practices demonstrate the intrinsic value of the arts as vehicles for information dissemination and cultural preservation in Zambian society.

Moreover, the use of the arts as tools for information dissemination has become particularly significant in cultures where literacy rates are lower or where there are language barriers. In Zambia, oral traditions and visual arts play crucial roles in overcoming these challenges and ensuring the accessibility of knowledge and information. Arts provide a universal language that transcends written words, allowing effective communication and engagement among diverse audiences. The use of visual imagery, storytelling, music, and dance enables individuals to connect with and comprehend complex concepts and messages even in the absence of formal literacy skills. This oral and visual tradition fosters inclusive participation of the community members, irrespective of their literacy levels, fostering a sense of belonging and shared understanding within the cultural context (Durán and Penn 2019).

Games and ‘Boostele’

Games, morale chants, and slogans, referred to as ‘Boostele’, have been recognised as valuable tools in different ways of knowing and visualisation. They offer interactive and engaging methods of communication and expression, enhancing learning, knowledge sharing, and collective understanding within communities (Kjørholt, Matafwali, and Mofu 2019; Mtonga, 1988; Kalobwe 2021). Games can be employed to delve into various concepts of WASH. In the case of DL, games were used for WASH education and the promotion of healthy practices.

Morale chants and slogans are potent tools for communication and motivation, serving to reinforce key messages, values, and behaviours associated with WASH practices. They also double as enjoyable ice breakers. These repetitive and rhythmic expressions aid in the internalisation of critical information and cultural norms, fostering a collective identity and responsibility toward WASH (Kjørholt, Matafwali, and Mofu 2019; Mtonga 1988), and transcending language and literacy barriers, thus promoting inclusive participation and effective information dissemination. These activities draw from cultural traditions and oral storytelling practices, enhancing engagement and knowledge transfer within communities (Kjørholt, Matafwali, and Mofu 2019). While the specifics of their use may vary across cultures and contexts, their potential lies in their ability to facilitate interactive learning, encourage cultural exchange, and empower individuals and communities to actively contribute to knowledge and solutions (Kjørholt, Matafwali, and Mofu 2019).

Communal Discussions

Various visual cues and activities create an environment for the exploration and open discussion of shared themes among community members. The mode of communication between DL youths and adults and DL youths and children was strikingly different. While DL youths and adults had discussions on community WASH problems and solutions, DL youths took on the task of teaching attendees who were children. In contrast, DL children and their peers engaged with each other during play. Many children attended the open DL events that were prompted by their peers. Adults attended the events based on both youth and children’s invitations but were less likely to attend events that comprised mainly children.

Discussion patterns at community events and exhibitions often reflect social norms and hierarchical structures. During the Sanitation Exhibition, DL members from one research site observed distinct communication dynamics among different age groups. Zambian society typically upholds a hierarchical structure where adults hold decision-making power and children are expected to respect their authority (Kjørholt, Matafwali, and Mofu 2019). This was evident in the DL exhibition, where DL youths and adults engaged in discussions on community WASH problems and solutions, highlighting the importance of intergenerational dialogue and knowledge exchange. Conversely, DL children interacted with their peers through play and peer-to-peer learning, creating an environment conducive to shared exploration and participation (Mtonga 1988).

Most Zambian cultures have a long-standing tradition of open community discussions as a means of collective problem-solving. These discussions often involve the participation of diverse community members, including youths, adults, and older adults. The practice of open community discussions allows the sharing of different perspectives, experiences, and knowledge, leading to the identification of community priorities and collaborative solutions. Open community discussions play a vital role, enabling individuals to collectively address social challenges and promote community development (Kjørholt, Matafwali, and Mofu 2019). In the context of WASH, open-community discussions facilitate the identification of local needs, barriers, and innovative strategies for improving water, sanitation, and hygiene practices, ensuring that interventions are contextually relevant and sustainable.

Public Intervention Activities

The key public intervention activities conducted by the DL were waste collection, sorting, and handwashing training. In the case of waste collection, interested community members were provided with tools (gloves, garbage bags, bins, etc.) and asked to take part in the waste collection either through official invitations (letters to schools, churches, and other community organisations), open calls on loudspeakers during events, or door-to-door visits. For open-door public events, community participation was higher than expected, with DL running out of materials to include all people willing to participate. Most willing participants were children and youth. Participation in formal waste management facilitates engagement. Through their participation in waste collection, community members learned about waste types and sorting.

Experiential learning theory, developed by David Kolb in 1984 (Kolb, Boyatzis and Mainemelis 2014), emphasises the importance of learning through direct experience and active engagement with the environment. According to this theory, individuals learn best when they are actively involved in the learning process, in which they can observe, experience, reflect upon, and apply their knowledge to practical situations. The ‘seeing and doing’ approach employed by DL members during the festival aligns with the principles of experiential learning as it encourages participants to engage their senses, actively participate in activities, and learn through first-hand experiences. By providing opportunities for participants to directly observe and interact with festival activities, DL members aimed to facilitate comprehensive learning and meaningful engagement in the context of sanitation and hygiene.

Stakeholder Observations and Feedback

Post-event feedback was requested from researchers, academics, civic leaders, WASH professionals, community members and DL members. Film 5 (Hanyika 2019e) provides comments. A basic thematic analysis was conducted on the 16 comments from these five stakeholder groups, as follows:

1. Community Empowerment and Engagement:

This theme revolved around the community’s desire for ongoing programs and events to educate and sensitise people about sanitation and hygiene. There was a strong belief that community engagement and education were fundamental to driving positive changes in WASH practices. Community members recognised the need for continuous efforts to raise awareness and foster active participation in addressing WASH challenges.

2. Responsibility for Sanitation and Hygiene:

The responsibility to maintain clean and proper sanitation facilities is a central theme. Community residents acknowledged their role in ensuring the cleanliness and functionality of toilets and the sanitation infrastructure. Some expressed concerns about the existing state of sanitation facilities, emphasising the need for improvements to enhance hygiene and sanitation practices.

3. Appreciation for Dziko Langa’s Work:

This theme highlights the community’s gratitude for the efforts of Dziko Langa in raising awareness and taking practical steps to address WASH issues. Community members recognised and valued the impact of visual materials, particularly photographs, on effectively conveying the seriousness of sanitation and hygiene challenges, thereby increasing community awareness.

4. Partnership and Collaboration:

Partnership and collaboration were central to this theme, as positive statements from community officials indicated a willingness to work with organisations, such as DL, to tackle sanitation and hygiene issues. Schools also acknowledged Dziko Langa’s role in educating and sensitising students and the broader community, emphasising the importance of collaborative efforts to promote WASH practices.

The visualisation of the community brought a sense of community identity to attendees. In their feedback, many residents spoke of their actions as collective communities and how these actions contributed to the community’s WASH environment. When faced with the image of their community, residents were able to appreciate the work of the DL. Likewise, public officials who were attendees at events pledged to support DL’s work in their communities, citing DL as a proactive group working for disease prevention. The platform for multi-stakeholder engagement also allowed community residents to collectively seek government assistance, recognising the need for regular public action through education to help change behaviour.

The importance of the involvement of children and youth in playing an active role in sustainability and change in peri-urban WASH was also recognised. The children and youth showed exceptional teamwork and displayed what they had learned through their participatory research, alongside various trainings, lessons, and events. Visiting other booths, attending sessions, and discussing with various stakeholders positively affected their understanding of the key issues affecting their communities. This has had an impact on their thoughts and plans for DL in the future.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The feedback received from participants in interviews and reviews underscores the substantial impact of visualization on community engagement, collective action, and the empowerment of children and youth in the context of WASH. Visualizing the community through exhibitions, photographs, and interactive activities fosters a sense of community identity and collective responsibility. Residents expressed their appreciation for DL’s work and stressed the need for ongoing sensitization and community involvement in WASH initiatives. Visualization of community challenges and potential for improvement motivated residents to take ownership of their WASH and waste practices. This impact extended beyond individual behavioural changes as residents recognized DL’s role in fostering a culture of cleanliness and disease prevention and were empowered to collectively seek government assistance and advocate for ongoing public action through education.

The visual evidence presented by DL allowed academics, researchers, and government officials to witness the real situation in communities, challenging preconceived notions and prompting a change in mindset. It also garnered support from government officials who recognized the urgency of addressing challenges like improper waste management considering its impact on public health (Civic Leader- Sanitation Exhibition 2018). Visualization was therefore recognised as a powerful tool for raising awareness and driving change.

The feedback also stressed the importance of involving children and youth in fostering sustainability and change. DL’s participatory research methods and events offered a platform for children and youth to actively participate, learn, and express their ideas. They gained confidence, teamwork skills, and a deeper understanding of critical issues affecting their communities. Visualisation activities, combined with interactions with stakeholders and exposure to different perspectives, expanded their knowledge and broadened their plans for DL’s future initiatives. The involvement of children and youth in visualising WASH issues showcases their potential as change agents and underscores the significance of their active participation in shaping sustainable practices and community development.

In summary, through various activities, visualisations were used to facilitate communication and foster engagement among participants and the broader community. This approach transformed individual experiences and daily life challenges into collective issues that could be addressed collaboratively. When considering the concept of ‘Different ways of knowing’ concerning the acquisition and processing of WASH information and knowledge within peri-urban communities in Lusaka, Zambia, it becomes evident that revaluating the development of programs and campaigns for WASH improvements is warranted. By exploring alternative approaches that incorporate local and traditional visualisation techniques, more effective means of reaching and engaging target audiences can be achieved.

References

- Boal, A.

- 1992

- Games for Actors and Non-Actors. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bunn, C., C. Kalinga, O. Mtema, S. Abdulla, A. DIllip, J. Lwanda, S. M. Mtenga, J. Sharp, Z., Strachan, and C. M. Gray

- 2020

- Arts-Based Approaches to Promoting Health in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review. BMJ Global Health 5 (5). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001987

- Central Statistical Office (CSO)

- 2012

- Zambia 2010 Census of Population and Housing: Population Summary Report.

- 2016

- 2015 Living Conditions Monitoring Survey (LCMS) Report. https://www.zamstats.gov.zm/backup/phocadownload/Living_Conditions/2015%20Living%20Conditions%20Monitoring%20Survey.pdf

- Durán, L., and H. Penn

- 2019

- Growing into Music. In A. T. Kjørholt and H. Penn (eds.) Early Childhood and Development Work: Theories, Policies, and Practices: 193-207. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hine, G.

- 2013

- The Importance of Action Research in Teacher Education Programs. Issues in Educational Research 23 (2): 151-163.

- Kalobwe, L.

- 2021

- The Patriotic Front’s Use Popular Music in the 2016 Elections in Zambia: A Literature Review. SocArXiv April 9. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/wt86k

- Kapata, N., N. Sinyange, M.L. Mazaba, K. Musonda, R. Hamoonga, M. Kapina, K. Zyambo, W. Malambo, E. Yard, M. Riggs, and R. Narra

- 2018

- A Multisectoral Emergency Response Approach to a Cholera Outbreak in Zambia: October 2017-February 2018. Journal of Infectious Disease 218 (3): S181–S183. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiy490

- Kjørholt, A. T., B. Matafwali, and M. Mofu

- 2019

- ‘The Knowledge Is in Your Ears, in the Stories You Hear from the Grandparents’: Creating Intercultural Dialogue Through Memories of Childhood. In Kjørholt and Penn (eds.) Early Childhood and Development Work: Theories, Policies, and Practices: 165-191. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kolb, David A., R. E. Boyatzis, and C. Mainemelis

- 2014

- Experiential Learning Theory: Previous Research and New Directions. In R. J. Sternberg and L. Zhang (eds.) Perspectives on Thinking, Learning, and Cognitive Styles. Routledge: 227-247.

- Kumar, S., V. K. Maurya, and S. K. Saxena

- 2020

- Water-Associated Infectious Diseases. In S. K. Saxena (ed.) Emerging and Re-emerging Water-Associated Infectious Diseases: 27-51. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9197-2_5

- Meyer, R.

- 2010

- Knowledge Visualization. Trends in Information Visualization 23: 23-30.

- Mtonga, M.

- 1988

- Children’s Games and Plays in Zambia (Doctoral dissertation, Queen’s University of Belfast).

- Nyambe, S., Y. Kataoka, H. Harada, and T. Yamauchi

- 2022

- Participatory Action Research for WASH by Children and Youth in Peri-Urban Communities. In T. Yamauchi, S. Nakao, and H Harada (eds.) The Sanitation Triangle: 151-174.

- Nyambe, S. and T. Yamauchi

- 2021

- Peri-Urban Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Lusaka, Zambia: Photovoice Empowering Local Assessment via Ecological Theory. Global Health Promotion 29 (3): 66-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975921995713

- Nyambe, S., L. Agestika, and T. Yamauchi

- 2020

- The improved and the unimproved: Factors influencing sanitation and diarrhoea in a peri-urban settlement of Lusaka, Zambia. PloS one 15 (5): e0232763. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232763

- Nyambe, S., K. Hayashi, J. Zulu, and T. Yamauchi

- 2018

- Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, Health and Civic Participation of Children and Youth in Peri-Urban Communities: An Overview of Lusaka, Zambia. Sanitation Value Chain 2 (1): 39-054. https://doi.org/10.34416/svc.00010

- Ogawa, A. 小川 明子

- 2016

- Dejitaru Sutoriiteringu: Koenaki omoi ni monogatari wo (Digital storytelling: making stories for unvoiced voices) 『デジタル・ストーリーテリング―声なき想いに物語を』Tokyo: Liberuta Shuppan リベルタ出版.

- Republic of Zambia

- 2006

- Fifth National Development Plan. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2007/cr07276.pdf

- Serpell, R., and J. Jere‐Folotiya

- 2008

- Developmental Assessment, Cultural Context, Gender, and Schooling in Zambia. International Journal of Psychology 43 (2): 88-96.

- Tuwe, K.

- 2016

- The African Oral Tradition Paradigm of Storytelling as a Methodological Framework: Employment Experiences for African communities in New Zealand. African Studies Association of Australasia and the Pacific (AFSAAP) Proceedings of the 38th AFSAAP Conference: 21st Century Tensions and Transformation in Africa. Deakin University.

- Wachege, P. N. and F. G. Rũgendo

- 2017

- Effects of Modernization on Youths’ Morality: A Case of Karũri Catholic Parish, Kenya. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 7 (12): 691-711. http://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i12/3704

- Wang, C., and M. A. Burris

- 1997

- Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. Health Education and Behavior 24 (3): 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global Task Force on Cholera Control

- 2011

- Cholera Country Profile: Zambia.

- World Health Organization (WHO), and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

- 2017

- Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines. Geneva: WHO & UNICEF.

- World Health Organization (WHO)

- 2018

- Guidelines on Sanitation and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/274939/9789241514705-eng.pdf?sequence=25&isAllowed=y (accessed September 1, 2023)

Films

- Hanyika, S.

- 2019a

- Introduction to Dziko Langa. Produced by Redhorse Media Productions, Lusaka, 03:25.

https://vimeo.com/876599667 (Retrieved January 1, 2024) - 2019b

- Participatory Methods (Photovoice, Art). Produced by Redhorse Media Productions, Lusaka, 03:09.

https://vimeo.com/876600155 (Retrieved January 1, 2024) - 2019c

- Dziko Langa Member Visualizations. Produced by Redhorse Media Productions, Lusaka, 05:39.

https://vimeo.com/876600271 (Retrieved January 1, 2024) - 2019d

- Dziko Langa - Our Work, Our Story (Digital Storytelling). Produced by Redhorse Media Productions, Lusaka, 03:05.

https://vimeo.com/876600355 (Retrieved January 1, 2024) - 2019e

- Community Engagement and Feedback. Produced by Redhorse Media Productions, Lusaka, 05:31.

https://vimeo.com/876600441 (Retrieved January 1, 2024)

Contact

Sikopo Nyambe

*Replace “■” with “@”.

Yoshimi Kataoka

*Replace “■” with “@”.

Samuel Hanyika

*Replace “■” with “@”.

Taro Yamauchi

*Replace “■” with “@”.