The most visible developments in visual anthropology in 21st century Taiwan have been the continuing activities of the Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival (TIEFF) and the increasing number of indigenous people documentaries.

The Taiwan Association of Visual Ethnography initiated the biennial TIEFF in 2001. TIEFF, the first and the longest running International Ethnographic Film Festival in Asia, screens films in the theatre in Taipei City. Until 2019, TIEFF had screened 365 local and foreign documentaries, of which 63 (17.2%) focused on Taiwanese indigenous people.

This article depicts the history, characteristics, criteria for selection, and impacts of TIEFF, and analyses Taiwanese indigenous people documentaries screened there. The term “indigenous people documentaries” is used to indicate indigenous-themed documentaries made by directors of both indigenous and non-indigenous descent. Six representative indigenous people documentaries made by the indigenous and Han Chinese directors have been selected for comparison to determine the representations, achievements, limitations, and contributions to anthropological knowledge of ethnographic filmmaking in Taiwan.

Key Words Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival (TIEFF), indigenous people documentaries, indigenous director, Taiwan, visual anthropology

The Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival and the Rise of Indigenous People Documentaries in Taiwan

(Published March 31, 2021)

Table of Contents

Abstract

In 21st century Taiwan, the most visible developments in visual anthropology have been the ongoing activities of the Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival (TIEFF), as well as the increasing number of documentaries about indigenous people it has screened. Given this significance, and that the biennial TIEFF (the official website: https://www.tieff.org/en/) is the first and longest running international ethnographic film festival in Asia, it is crucial to consider the following details: how and why it began; how it differs from ethnographic film festivals in Western countries; and how TIEFF is related to the proliferation of documentaries on Taiwanese indigenous people.

This article not only depicts the history, themes, characteristics, criteria for selection, and impacts of TIEFF, it also discusses the socio-political background and the specific designs of TIEFF for the rise of indigenous people documentaries.

Six representative Taiwan indigenous people documentaries made by the indigenous and Han Chinese directors are selected for comparison to find out the main topics, ways of representations, and contributions of these films to anthropological knowledge and social practices. This article further reveals the advantages and limitations of indigenous directors while filming their own societies.

I. The Birth and Main Characteristics of TIEFF

I am a Taiwanese anthropologist, and I began making 16mm ethnographic films in 1984. For years, I screened my ethnographic documentaries at international ethnographic film festivals in Europe and North America. However, I always hoped that an international ethnographic film festival could be established in Taiwan. In 2000, several visual anthropologists and documentary filmmakers created the Taiwan Association of Visual Ethnography (TAVE), a non-profit organisation supported by Academia Sinica’s Institute of Ethnology. In 2001, this organisation coordinated the first TIEFF. I was brought in at that time as president of TIEFF, a position I have maintained to the present day, and I was also the festival director and programmer of the first and second TIEFF.

TIEFF accepts entries in two categories of film. The ‘Theme’ category calls for entries of films that focus on a particular theme, and TIEFF then invites a particular director (since 2007 two directors) to serve as ‘director in focus’ and talk about that theme. In the ‘New Vision’ category, films completed on any subject within the last two years can be submitted. TIEFF categorises the selected films into various programmes and invites scholars to write review essays for the film catalogue. The selection criteria define ethnographic documentary films broadly; films must only contain deep cultural meanings and encourage anthropological comparison and discussion to qualify. Docufictions with actors playing themselves – such as Robert Flaherty’s Moana, filmed in Samoa (screened at the 2001 TIEFF), and Park Chan-Kyong’s Manshin, about the renowned Korean shaman Kim Keum-hwa (screened at the 2015 TIEFF) – are eligible. However, TIEFF does not include entirely fictional films played by actors – such as Wei Te-sheng’s famous indigenous film Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale, based on the 1930 Wu-she Incident in Central Taiwan while it was under Japanese rule, or the Inuk director Zacharias Kunuk’s Atanarjuat The Fast Runner. At its last two festivals, TIEFF adopted a sophisticated registration system powered by FilmFreeway, which led to a significant increase in the number of submissions, from about 300–400 films annually, to 700–1000 annually. Each selected title is viewed and reviewed by at least two judges. The festival programmer consults with the judges and then decides the finalists, which always include films from Europe, Middle East, Africa, North and South America, but give more consideration to Asia-Pacific films.

The biennial TIEFF has always been held in the Wonderful Theatre (真善美劇院) in central Taipei City. Interested members of the public can buy tickets to see the TIEFF films. Since TIEFF considers every selected film to be equally valuable, it holds no competitions for its films. Instead, TIEFF emphasises cultural and professional exchanges among international and Taiwanese filmmakers, scholars, and general audiences. It seeks to provide a bilingual setting for cultural intercommunication and understanding by providing film subtitles, websites, catalogues, and post-screening discussions in languages other than Chinese. It also encourages intercultural comparisons and reflections on Taiwan’s socio-cultural issues. Next year, TIEFF will tour other parts of Taiwan with selected films.

The first TIEFF can be used as an illustration of the main characteristics of the festival. TIEFF’s emphasis extends from the local to the global, and since Taiwan is an island, the theme of the first TIEFF was ‘Island Odyssey’. In addition to the selected films about islands elsewhere, an ‘Orchid Island’ programme was planned. Taiwan’s Orchid Island, home of the Austronesian Yami/Tao indigenous people, has been the focus of many ethnographic documentaries. The audience of the first TIEFF was able to observe important cultural transformations in the selected ‘Orchid Island’ films: my own Voices of Orchid Island (made in 1993) opened the programme, and it continues with Huang Chi-mao’s Dishes of an Afternoon Meal, Lin Jian-Hsiang’s Rayon, Kuo Chen-ti’s Libangbang: Ching- wen’s Not Home, and the closing film And Deliver Us From Evil by Chang Shu-Lan (si Manirei), a nurse on Orchid Island and the founder of the Elderly Home Care Association of Orchid Island. These films depicted how the intersection of traditional concepts of Orchid Island’s indigenous people with the concepts of modern civilisation has created contradictions, struggles, joys, and tragedies.

My film Voices of Orchid Island was made with both theoretical and practical intentions. I wanted to form a new type of cooperation between ethnographic filmmakers and natives, and thus provide a platform for a variety of voices. The delicate power relations between the filmmaker and the filmed subject are shown in the opening of the film, when a Yami/Tao friend says to me, ‘I hope you can be a friend to us, can adopt the view of studying ethnic minority culture. In particular, I hope this film can be used in some ways’. Another young Yami/Tao collaborator said:

We tend to feel that the more anthropologists come here, the deeper the harm they do to the Yami. I feel anthropologists come to Orchid Island just so they can advance to a certain social status. They only use Orchid Island as a tool, they do not benefit the subjects of their research. I regret this very much.

This statement challenges not only anthropologists but also ethnographic filmmakers and their films. Professor Chiu Kui-fen, in her article ‘The Vision of Taiwan New Documentary’ (Davis and Robert Chen eds. 2007: 20), writes:

Voices of Orchid Island is an ethnographic documentary that tackles the issue of encounters between the aborigines and the socially dominant group outside the island and the complications that ensue. The film is celebrated as a milestone in the history of visual ethnography in Taiwan, for if traditionally aborigines are subject to the ethnographic gaze, the film deliberately unsettles the ease with which the ethnographer gazes at, films, and studies aboriginal subjects. Highly conscious of the danger of ‘speaking for’ her aboriginal subjects, Hu deliberately abandons voice-overs and interviews with on-camera experts interpreting the subjects’ lives.

The closing film of the first TIEFF was And Deliver Us from Evil by Chang Shu-Lan (si Manirei). I was greatly impressed by the closeness and intimacy with the elderly people on Orchid Island that this film achieved. It demonstrates the value and power of the films made by the indigenous directors. Shu-Lan hoped that her film could help improve activities in retirement homes on the island. At the same time, she worried that the images she provided of the elderly people’s living conditions on the island would cause outsiders to misunderstand the Yami/Tao culture.

The first TIEFF also screened other famous ethnographic films, such as Moana: A Romance of the Golden Age, filmed on the Samoa Islands in 1926 by Robert Flaherty, and three films shot by Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson in Bali and Papua New Guinea from the 1930s to the 1950s: Kaba’s First Years, Childhood Rivalry in Bali and New Guinea, and Trance and Dance in Bali. For the Director in Focus, TIEFF invited the outstanding Australian documentary director Dennis O’Rourke to Taiwan to present three of his films related to the theme of ‘Island Odyssey’. Since 1975, Dennis O’Rourke has focused his work on the Pacific Islands, documenting the transformation in Papua New Guinea and other islands after colonisation. The first TIEFF opened with O’Rourke’s Cannibal Tours, a humorous and satirical comparison between the past cannibal traditions of Papua New Guinea and the modern tourist cannibal culture. His other films concerned with the meeting of islanders and foreign cultures include The Sharkcallers of Kontu and Half Life: A Parable for the Nuclear Age, both of which show how indigenous cultures argue for their right to continued existence.

TIEFF emphasises comparative perspectives, and the selected films in categories of ‘Theme’ and ‘New Vision’ can be compared to reveal deeper cultural meanings. Although limited by its budget, TIEFF tried to invite as many directors of the selected films as possible to view and discuss their films with audiences during the 5-day festival.

As shown in Table 1 below, TIEFF put on ten different festivals from 2001 to 2019, each with a distinct theme. TIEFF had four different festival programmers during this period, all visual anthropologists working in research institutes or universities in Taiwan. As mentioned above, I was the festival director and programmer for the 2001 and 2003 TIEFFs; in addition to being a filmmaker, I am also a research fellow at Academia Sinica’s Institute of Ethnology. Lin Wen-Ling, a professor in National Chiao Tung University’s Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, was the director and programmer of the 2005, 2007, and 2009 TIEFFs. Futuru C. L. Tsai, an assistant (now associate) professor in National Taitung University’s Department of Public and Cultural Affairs, was the director and programmer of the 2011, 2013, and 2015 TIEFFs. Kerim Friedman, an associate professor in National Dong Hwa University’s Department of Ethnic Relations and Cultures, programmed the 2017 and 2019 TIEFFs. At the most recent festival, Futuru C. L. Tsai was the festival director and shared some of the programming duties as well. Since the 2017 TIEFF, there have been some changes to the personnel structure of the festival. Huang Shih-chun, the coordinator for domestic affairs, has been promoted to administrative supervisor so that she can run the festival more effectively and smoothly.

Table1 TIEFF programmers, themes and directors in focus, 2001-2017

| Year | Festival director and programmer | Theme of TIEFF | Directors in Focus | Presented films |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Hu Tai-Li | Island Odyssey | Dennis O'RO'Rourke |

Cannibal Tours/ The Sharkcallers of Kontu/ Half Life |

|

Robert Flaherty (retrospective) |

Moana: A Romance of the Golden Age |

|||

|

Margaret Mead &Gregory Bateson (retrospective) |

Kaba First Years/ Childhood Rivalry in Bali and New Guinea/ Trance and Dance in Bali | |||

| 2003 | Hu Tai-Li | Migration Story | Jean Rouch | Moi, Un Noir (Me, a Black)/ Jaguar/ Les Maitres Fous (The Crazy Masters) |

|

M.Harrison, M.C.Cooper & E.B. Schoedsack (retrospective) |

Grass: A Nation’s Battle | |||

|

Yang Guanghai (retrospective) |

The Oroqen | |||

| 2005 | Lin Wen-Ling | Family Variations | David& Judith MacDougall | Lorang’s Way/ A Wife Among Wifes/ The House Opening |

| John Marshall | A Kalahari Family: A Far Country/ End of the Road | |||

| 2007 | Lin Wen-Ling | Indigenous Voices |

Victor Masayesva |

Imagining Indians/ Water land Life-H2opi Run to Mexico |

|

Mayaw Biho |

Children in Heaven/ Carry the Paramount of Jade Mountain on My Back/ Dear Rice Wine, You are Defeated | |||

|

Robert Gardner (retrospective) |

Dead Birds | |||

|

Miyamoto Nobuto(宮本延人) (retrospective) |

Pasta’ai: the Saisiyat Ceremony in 1936 | |||

|

Hu Tai-Li (retrospective) |

Songs of Pasta’ay | |||

| 2009 | Lin Wen-Ling | Body and Soul | Timothy Asch | A Balinese Trance Séance/ Releasing the Spirits – A Village Cremation in Bali |

|

Pilin Yapu |

The Stories of Rainbow/ Through Thousand Years | |||

| 2011 | Futuru C. L. Tsai | Suffering and Rebirth |

Robert Lemelson |

The Bird Dancer/ Family Victim |

|

Lungnan Isak Fangas |

Ocean Fever/ On the Road - Behind the Scenes, Director’s Cut | |||

| 2013 | Futuru C. L. Tsai | Beyond Borders | Trinh T. Minh-Ha | Surname Viet Given Name Nam / Reassemblage |

|

Salone Ishahavut |

Alis’s Dream/ Futau Fuzu, a Story of Love | |||

| 2015 | Futuru C. L. Tsai | Scenes of Life | Jorge Preloran | The Image Man/ Zulay, Facing the 21st Century |

|

Tang Shiang-Chu |

How Deep is the Ocean/ Pusu Qhuni | |||

| 2017 | Friedman,Kerim (programmer) Futuru C. L. Tsai (festival director) |

Beyond the Human |

Lucien Castaing-Taylor (with Verena Pavavel / Ilisa Babash) |

Leviathan/ Sweetgrass |

|

Etan Pavavalung |

Mountain Tribe, Sea Tribe/ Encounter in That End of the Forest | |||

| 2019 | Friedman,Kerim (programmer) Futuru C. L. Tsai (festival director) |

Visions of Sovereignty | Merata& Heperi Mita (Maori) | Merata: How Mom Decolonied the Screen/ Bastion Point Day 507 |

|

Uki Bauki (Kavalan) |

The Endurance to Become a Real Man / The Solemn Commitment to Palakuwan |

Table 1 also shows the theme of each TIEFF, the invited directors in focus, and the films they presented. Many important foreign ethnographic films translated into Chinese subtitles were thus introduced to the audience to aid teaching and promote visual anthropology in Taiwan. From 2007 onward, each TIEFF had two directors in focus: one domestic and one foreign. Domestic directors chosen by the festival directors/programmers were mostly indigenous directors, and the films of the chosen Han Chinese director in focus also concentrated on indigenous people. The growth of Taiwanese indigenous people documentaries has been a very prominent phenomenon at TIEFF.

II. The Rise of Indigenous People Documentaries

Since the development of video cameras in the late 1980s, the ethnographic documentary genre has undergone revolutionary transformations. The rapid advancement of video technology has created flexibility for the size, cost, and quality of video production. This has made recording and editing more user-friendly, and thus popularised filmmaking. Indigenous people that used to be relegated to the passive role of being filmed now have access to the training and technology necessary to make their own documentary films.

Taiwan has 16 officially recognised indigenous groups whose languages belong to the Austronesian language family, consisting of approximately 570,000 people and 2.4% of the entire population (cf. the website of Taiwan’s Council of Indigenous Peoples: https://www.cip.gov.tw/portal/docList.html? CID=200161A7D09A7FEC).

When I began filming 16mm documentaries on Taiwanese indigenous people in the 1980s, I consulted a friend in the field of television documentaries about obtaining support from network television. He told me that ‘Works concerning indigenous peoples evoke the dark and degenerate aspects of Taiwanese society. A TV Station would not support such works’. Indeed, from the period of the Japanese occupation (1895–1945) to that of governance by the Republic of China (1945 to the 1980s), documentaries in Taiwan were supervised by the state. To be considered legitimate, the documentary films had to either pay lip service to the government, which was desperate to educate the people (Daw-Ming Lee 1994), or serve as international propaganda, projecting a positive image of Taiwan to the world.

With the lifting of martial law in 1987, previously marginalised ethnic groups and communities began their struggle for self-governance, land and naming rights, and the well-being. In 1996, the Executive Yuan’s Council of Aboriginal Affairs (renamed the Council of Indigenous Peoples in 2002) was founded. The Taiwan Public Television Service (PTS) went on the air in 1998, featuring the documentary programme Aboriginal News Magazine, produced by newly trained journalists of indigenous descent. In 2005, the Taiwan Indigenous Television Station was launched and became affiliated with the corporate body of PTS. Aboriginal News Magazine and some of its crew were then transferred to the Indigenous Television Station. Additionally, the non-governmental Full Shot Studio received a three-year grant from the Council for Cultural Affairs (now the Ministry of Culture) in 1995 to cultivate the work of local documentary makers, including quite a few indigenous people who learned the technical skills to make documentary films independently. In this shifting political climate, documentaries based on indigenous people or indigenous themes began to grow.

Before the popularisation of video cameras, documentary directors working with 16mm cameras and film stock were all Han Chinese. Things began to change in the mid-1990s, when a few indigenous documentary directors came on the scene. Operating with inexpensive and lightweight video cameras and editing equipment, they threw themselves into documentaries of indigenous culture and society. Mayaw Biho from the Amis tribe was the earliest indigenous director. After earning his B.A. in film and visual art, he worked as a journalist for PTS’s Aboriginal News Magazine before joining the crew of a documentary programme on Super TV as a writer-director. Submitting proposals for his documentaries to institutions such as Public TV, the National Culture and Arts Foundation, and the Council of Indigenous Peoples, he became a full-time documentary director. His first documentary short, Children in Heaven (1997), won the PTS Judges’ Recommendation Award at the First Taiwan International Documentary Festival held in 1998, becoming the first indigenous documentary by an indigenous director to make headway at an international film festival. The 2007 TIEFF chose Mayaw Biho as the Director in Focus, screening three of his films: Children in Heaven (1997), Dear Rice Wine, You Are Defeated (1999), and Carry the Paramount Jade Mountain on My Back (2002).

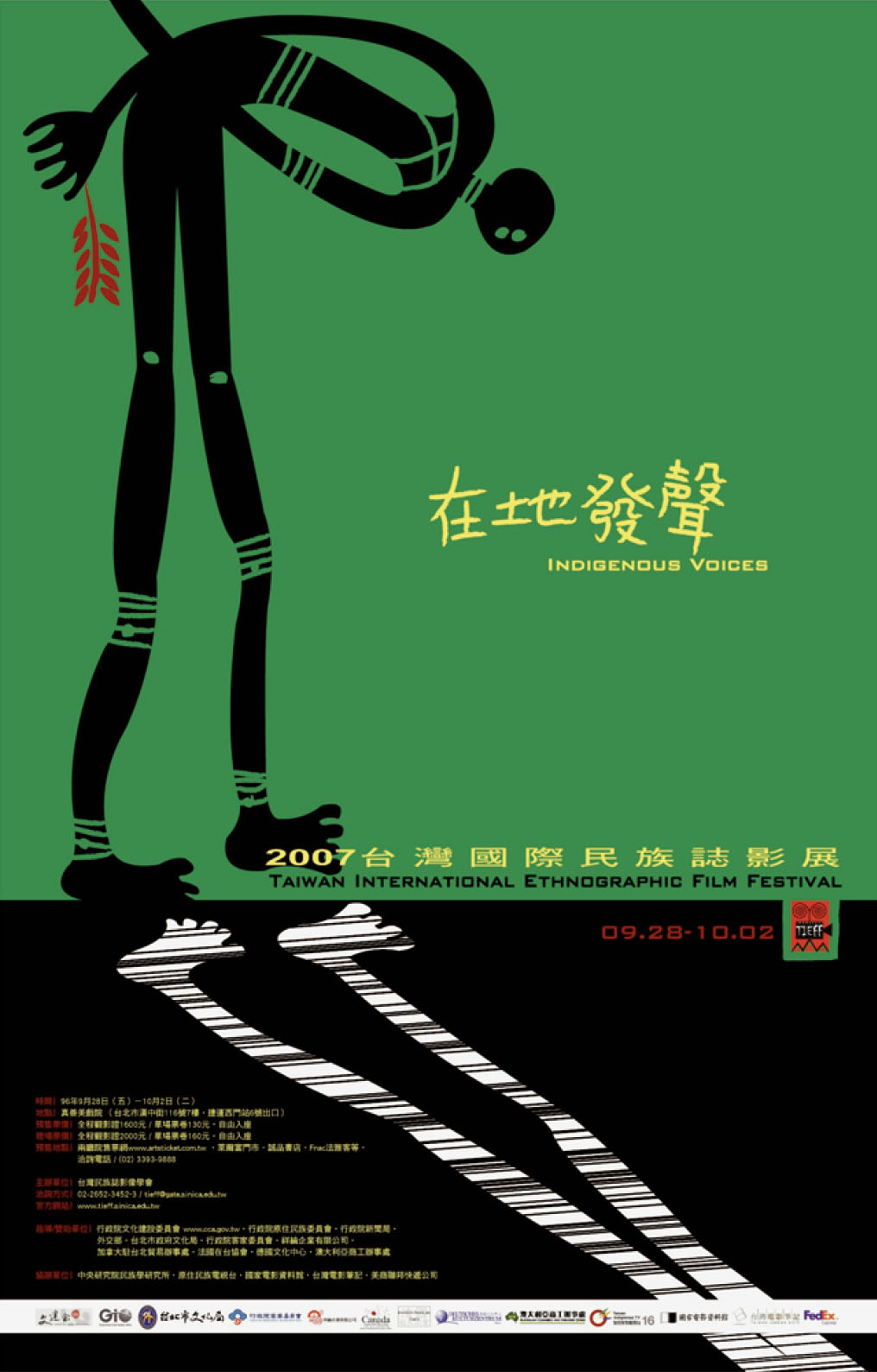

To understand the role that TIEFF has played in giving voice to indigenous groups, it is worth looking at the 2007 TIEFF in particular. The theme of the 2007 TIEFF was ‘Indigenous Voices’, intended to highlight documentaries on indigenous people and indigenous directors (Figure 1). The Taiwanese indigenous director Mayaw Biho from the Amis tribe and the outstanding Hopi American filmmaker Victor Masayesva were selected as the directors in focus. The 2007 TIEFF also screened films made by other indigenous directors, such as films from Brazil’s Video in the Villages Project, the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association, and Taiwan Indigenous Television. Professor Faye Ginsburg, a visual anthropologist from New York University, was invited to discuss these indigenous films.

Figure 1 The poster of 2007 TIEFF

Figure 1 The poster of 2007 TIEFF©Taiwan International Ethnographic Festival (TIEFF)

The term ‘indigenous documentaries’ is usually used by scholars to denote documentaries made by indigenous directors (Lin Wen-Ling 2001; 2003; 2005). I prefer the term ‘indigenous people documentaries’ (Hu Tai-Li 2013), which indicates indigenous-themed documentaries made by directors of both indigenous and non-indigenous descent. Though it focused on giving a voice to the indigenous peoples, the 2007 TIEFF did not restrict its films to those made by indigenous directors, as our organisation believes that non-indigenous documentary filmmakers should be able to share the sights and sounds of indigenous life as well. TIEFF wishes to see these different interpretations coalesce to create new meaning.

In the retrospective portion of the 2007 TIEFF, Robert Gardner’s celebrated film Dead Birds (1963) played an important role in representing the works of non-indigenous productions on indigenous culture. Karl Heider, a fieldworker and researcher for this film and distinguished professor of Anthropology at the University of South Carolina, participated in the 2007 TIEFF and talked about the history and the making of this classic documentary.

The 2007 TIEFF also screened two films about the Pasta’ay ceremony of the Saisiyat people, a well- known indigenous cultural heritage of Taiwan. One was Pastaai - The Saisiyat Ceremony in 1936 by the Japanese scholar Nobuto Miyamoto (宮本延人). Miyamoto’s pioneering films were forgotten for several decades but they were rediscovered in the archives of National Taiwan University’s Department of Anthropology in 1994. In cooperation with the National Film Archives, the films were digitised to preserve them for posterity. The 2007 TIEFF was the first public screening of Miyamoto’s silent and minimally edited film on the Saisiyat ceremony, an important event in the history of the Taiwanese ethnographic film. Another film on this ceremony shown at the 2007 TIEFF was Songs of Pasta’ay, by Lee Daw-Ming and myself. It was filmed half a century later, in 1986, at the same Saisiyat village. Taken together, the two films reveal both the changes and the continuity of this valuable cultural heritage over time. TIEFF also invited Saisiyat representatives to the theatre to view the films and participate in the related discussions.

From 2001 to 2019, TIEFF screened a total of 365 documentaries. 260 (71.2%) were from foreign countries and 105 (28.8%) were from Taiwan (Table 2). Among the 105 Taiwanese films, 63 focused on indigenous people, among which 39 were made by Taiwan’s indigenous directors. TIEFF has thus provided a significant showcase for the increasing number of indigenous people documentaries in Taiwan.

Table 2 Characteristics of films selected by TIEFF (2001–2019)

| Year | selected films | total | Taiwan indigenous people films | Films by Taiwan indigenous directors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| domestic | foreign | ||||

| 2001 | 11 | 23 | 34 | 8 | 2 |

| 2003 | 12 | 21 | 33 | 4 | 1 |

| 2005 | 12 | 28 | 40 | 4 | 3 |

| 2007 | 15 | 27 | 42 | 10 | 7 |

| 2009 | 11 | 23 | 34 | 5 | 3 |

| 2011 | 10 | 26 | 36 | 7 | 6 |

| 2013 | 11 | 23 | 34 | 8 | 5 |

| 2015 | 8 | 27 | 35 | 5 | 2 |

| 2017 | 8 | 34 | 42 | 7 | 5 |

| 2019 | 7 | 28 | 35 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 105 | 260 | 365 | 63 | 39 |

| percentage | 28.8% | 71.2% | 100% | 17.2% | 10.7% |

TIEFF has offered indigenous directors in Taiwan a chance to be seen, recognised, and honoured. From 2007 to 2019, six indigenous directors were designated as TIEFF’s Director in Focus: Mayaw Biho, Pilin Yapu, Lungnan Isak Fangas, Salone Ishahavut, Etan Pavavalung, and Uki Bauki. TIEFF also focuses on non-indigenous directors, however; at the 2015 TIEFF, the domestic Director in Focus was Tang Hsiang-chu, of Han Chinese descent. The festival screened two of his films related to indigenous people: How Deep Is the Ocean (1999), which documents the life of a Yami/Tao man Si-Mamuno, and Pusu Qhuni (2013), which captures the lives of the descendants of the Seediq people who survived the horrors of the Wushe Incident, a 1930 uprising against Japanese colonial rule which resulted in the deaths of 134 Japanese and a severe backlash.

TIEFF has also provided great opportunities for directors of Taiwanese indigenous people documentaries to see quality ethnographic films from abroad, and to communicate directly with foreign directors. It is difficult to judge the impact of foreign ethnographic films on indigenous Taiwanese filmmaking. However, it is clear that the international atmosphere of TIEFF which invited around 10 foreign directors of selected films each time allows directors of different backgrounds to become one family and learn from each other. In addition, through TIEFF’s mediation, several Taiwanese indigenous people documentaries were screened at the Jean Rouch International Film Festival in Paris, the International Intangible Heritage Film Festival in Korea, the Taiwan Film Festival at Australian National University, and the National Museum of Ethnology in Japan.

From Table 3, we can see the wide range of topics in the 63 Taiwanese indigenous people documentaries screened at TIEFF. However, certain themes recur often: protests against governmental policies, the search for one’s roots and identity, historical events, maintaining traditions in modern times, ritual practices, cultural revitalisation, natural disasters, and youth education. The following section puts emphasis on the ways of representation of the indigenous people documentaries.

Table 3 Indigenous people documentaries selected by TIEFF (2001–2019)

| No. | year | film title/ length/ format/ production year | director | director’s ethnicity | filmed ethnic group | key words of the film content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2001 |

The Last Chieftain 118min/16mm/1999 |

Daw-Ming Lee & Sakuliu Pavavalung | Han Chinese & Paiwan | Paiwan | Paiwan chiefs and political change |

| 2 | 2001 |

After Championship 60 min/VHS/2000 |

Tseng Wen-Chen | Han Chinese | Puyuma | Young baseball players’ struggle |

| 3 | 2001 |

She Sometimes A God 36 min/VHS/1999 |

Chiang Mei-Ju | Han Chinese | Siraya | A female Siraya medium possessed by the spirit Alizu |

| 4 | 2001 |

Dishes of An Afternoon Meal 30 min/VHS/1996 |

Huang Chi-Mao | Han Chinese | Yami/Tao | The director recorded the daily lives of his Tao “family”. |

| 5 | 2001 |

Libangbang: Ching-Wen’s not Home 30 min/35mm/2000 |

Kuo Chen-Ti | Han Chinese | Yami/Tao | A young Tao working in the city and his family |

| 6 | 2001 |

Rayon 40 min/VHS/1997 |

Lin Jian-Hsiang | Han Chinese | Yami/Tao | Flying fish and the ceremony |

| 7 | 2001 |

And Deliver Us From Evil 54 min/VHS/2001 |

Chang Shu-Lan (si Manirei) | Yami/Tao | Yami/Tao | Tao evil spirits and sick people |

| 8 | 2001 |

Voice of Orchid island 72 min/16mm/1993 |

Hu Tai-Li | Han Chinese | Yami/Tao | Against tourists’ camera, modern medicine, and the nuclear waste |

| 9 | 2003 |

Dreaming of Home – Marginal Tribe of the City 24 mins/VHS/1997 |

Tsao Wen-Chieh | Han Chinese | Amis | Amis migrants’ home in the city and the youths |

| 10 | 2003 |

Wuhaliton: Tears of the Moon 26 min/VHS/2003 |

Salon Ishahavut | Bunun | Bunun | Bunun legend: one sun was shot and became the moon. |

| 11 | 2003 |

Dawu Melody 47 min/VHS/2003 |

Lin Chien-Hsiang | Han Chinese | Yami/Tao | Musical world of the Tao people |

| 12 | 2003 |

Silent Cello 54 min/VHS/2003 |

Shen Ko-Shan & Chang Han | Han Chinese | Bunun | American cellist David Darling and Bunun kids’ voice |

| 13 | 2005 |

Kimbo in a Flash 24 min/VHS/2005 |

Halugu Watan & Galah Kalahe | Atayal & Saisiat | half Paiwan and half Puyuma | The singer Kimbo Hu and aboriginal movement |

| 14 | 2005 |

The Solicitude for the Takasago Volunteer /td>

31 min/VHS/2005< | Watan & Olom | Atayal & Amis | aboriginal Takasago volunteers | Mr.Tomohide Kadowaki’s devotion to taking care of Takasago volunteers |

| 15 | 2005 |

Stone Dream 79 min/16mm/2004 |

Hu Tai-Li | Han Chinese | veteran mainlanders and indigenous wives | The veteran mainlander Liu Pi-Chia and his indigenous wife and son in Hualien |

| 16 | 2005 |

Trakis na bnkis 23 min/VHS/2003 |

Baunay Watan | Atayal | Atayal | The revival of millet planting and related rituals |

| 17 | 2007 |

Pastaai - The Saisiyat Ceremony in 1936 19 min/16mm/1936 |

Nobuto Miyamoto | Japanese | Saisiyat | The Saisiayt Pastaai ceremony recorded by Nobuto Miyamoto in 1936 |

| 18 | 2007 |

Songs of Pastaay 60 min/16mm/1988 |

Hu Tai-Li & Daw-Ming Lee | Han Chinese | Saisiyat | Recording Pasta’ay Ceremony of 1986 to reflect Saisiat’s ambivalent feelings through the unique song pattern |

| 19 | 2007 |

Children in Heaven 13 min/VHS/1997 |

Mayaw Biho | Amis | Amis | Conditions of destroying the illegal Amis houses under the bridge in the urban setting. |

| 20 | 2007 |

Carry the Paramount of Jade Mountain on My Back 46 min/VHS/2002 |

Mayaw Biho | Amis | Bunun | Bunun Memories of carrying the bronze statue of Yu Yu-jen to the highest mountain |

| 21 | 2007 |

Dear Rice Wine, You are Defeated 24 min/VHS/1998 |

Mayaw Biho | Amis | Amis | Debate over drinking up a big bowl of rice wine in the upgrade ritual |

| 22 | 2007 |

When the Village Encounters the Country 28 min/VHS/2007 |

Pisuy Masaw & Vikung Lalegeam | Atayal & Paiwan | Atayal | The Smangus people fought for the right to use the tree fallen on their land |

| 23 | 2007 |

Conversation of Tali and Yaki 14 min/VHS/2002 |

Halugu Watan | Atayal | Atayal | A young Atayal man Tali decided to get face tattooing. |

| 24 | 2007 |

Retrospect Days of White Terrors 16 min/VHS/2006 |

Pisuy Silan & Kaleh Kalahe | Atayal & Saisiat | Atayal / Tsou | Stories of Taiwan aboriginals oppressed by the White Terrors |

| 25 | 2007 |

Si Yabosokanen 50 min/VHS/2007 |

Chang Shu-Lan (si Manirei) | Yami/Tao | Yami/Tao | Recording Tao elders’ attitudes toward aging, disease and death |

| 26 | 2007 |

Amis Hip Hop 49 min/VHS/2007 |

Futuru C. L. Tsai | Han Chinese | Amis | Blending modern Hip Hop with A’tolan traditional songs and dances |

| 27 | 2009 |

The Stories of Rainbow 55 min/DV/1988 |

Bilin Yabu | Atayal | Atayal | Viewpoints and lives of the elders who have tattooed their faces |

| 28 | 2009 |

Through Thousands Years 66 min/DV/2009 |

Bilin Yabu | Atayal | Atayal | Conflicts of a Han film team with the Atayal villagers recorded by the Atayal director |

| 29 | 2009 |

Kawut Na Cinat'Kelang 60 min/DV/2009 |

Lin Chien-Hsiang | Han Chinese | Yami/Tao | Building an extra large 14-person Tao boat and rowing from Orchid Island to Taiwan |

| 30 | 2009 |

Men's Ocean, Women's Calla Lily Field 24 min/VHS/2008 |

Hsieh Fu-mei | Yami/Tao | Yami/Tao | Recording the important roles of the Tao women during men’s boat building processes |

| 31 | 2009 |

Sing It ! 63 min/DV&HDV/ 2009 |

Shine Yang | Han Chinese | Bunun | The school principle Bukut led the Bunun kids choir |

| 32 | 2011 |

Ocean Fever 109 min/DV/2004 |

Lungnan Isak Fangas | Amis | Amis; Paiwan; Puyuma | Rock n’ roll bands including the indigenous totem band in Taiwan |

| 33 | 2011 |

On The Road - Behind the Scenes, Director’s Cut 80 min/HD/2004 |

Lungnan Isak Fangas | Amis | Puyuma | The film director’s perspective on indigenous music performance at the National Concert Hall |

| 34 | 2011 |

Light Up My Life 57 min/HD/2011 |

Mayaw Biho | Amis | Kanakanavu | Arbuwu efforts to rebuild her village after the big typhoon. |

| 35 | 2011 |

The New Flood 51 min/VHS/2011 |

Futuru C. L. Tsai | Han Chinese | Tsou | The Tsou flood legend and the new flood threat |

| 36 | 2011 |

Collected Ping-pu Memories - On Representing Kavalan and Ketagalan Voices and Images 53 min/DV/2011 |

Bauki Pan Chao-Cheng | Kavalan | Kavalan; Ketagalan | Plain aborigines’ searching for old recordings and films stored in Japan to revive tradition |

| 37 | 2011 |

My River 60 min/DV/2009 |

Mayaw Biho | Amis | Amis | The processes of building the Amis houses and then being torn down by the government continue under the bridge |

| 38 | 2011 |

Voices in the Clouds 77 min/DV/2010 |

Aaron Hosé | half Atayal and half American | Atayal | Tony’s searching for his mother’s roots in Taiwan |

| 39 | 2013 |

Alis’s Dreams 64 min/HD/2011 |

Salone Ishahavut | Bunun | Bunun | Alis insisted to stay in the old village after the big Moracot typhoon. |

| 40 | 2013 |

Fuzu a Story of Love 60 min/VHS/2011 |

Salone Ishahavut | Bunun | Tsou | Pu-u returned Tsou home and became an artist. |

| 41 | 2013 |

Memory of Islands 56 min/HD/2013 |

Syaman Chang Yeh-Hai | Yami/Tao | Yami/Tao | Orchid Island’s interactions with Batan Island in Philippines |

| 42 | 2013 |

The Last 12.8 km 56 min/HD/2013 |

Sasuyu Ubalat | Paiwan | Paiwan | Should the tribe keep Alangyi old path or build a new road? |

| 43 | 2013 |

Out of Place 78 min/HDV/2012 |

Hsu Hui-Ju | Han Chinese | Pingpu; Siraya | Searching lost plain indigenous identity and the typhoon destroyed Xiaoling village. |

| 44 | 2013 |

Sakuliu 2 : The Conditions of Love 88 min/HD/2013 |

Jofei Chen | Han Chinese | Paiwan | The Paiwan artist Sakuliu’s dilemma on leaving or returning home |

| 45 | 2013 |

Wushe Alan Gluban 54 min/HD/2012 |

Pilin Yabu | Atayal | Seediq | Descendants of Wushe Incident’s survivors tell the true story. |

| 46 | 2013 |

Returning Souls 85 min/DV/2012 |

Hu Tai-Li | Han Chinese | Amis | Reconstructing the Amis ancestral house with souls returning from the museum |

| 47 | 2015 |

How Deep is the Ocean 60 min/HD/2000 |

Tang Shiang-Chu | Han Chinese | Tao | The director and his Tao friend Mamuno shared common love for sea. |

| 48 | 2015 |

Pusu Qhuni 154 min/HD/2013 |

Tang Shiang-Chu | Han Chinese | Seediq | The lives and memories of Seediq survivors and descendents of Wushe Incident in Kawanaka island |

| 49 | 2015 |

Songs of Hunungaz 77 min/HD/2015 |

Wan Pei-Chyi, Wang Ying-Shun | Han Chinese | Bunun | The kids in the mini-sized school love to sing but their school faces the crisis of being shot down. |

| 50 | 2015 |

The Vast Deep Blue Ocean 70 min/HD/2015 |

Layway Dalay | Amis | Amis | Recording Amis men’s hard work on ocean fishing boats |

| 51 | 2015 |

The Mountain 61 min/HD/2015 |

Su Hung-En | Taroko | Taroko | The old hunter’s life experiences and the indigenous movement |

| 52 | 2017 |

Encounter in the End of the Forest 48 min/HD/2016 |

Etan Pavavalung | Paiwan | Paiwan | The director/artist depicts the tattooed Paiwan forest of his art works. |

| 53 | 2017 |

The Memory of Orality 51 min/HD/2017 |

Watan Kahat | Han Chinese | Atayal | A research team’s study of ancient Atayal singing Lmuhuw and its implications |

| 54 | 2017 |

Resurgence 53 min/HD/2016 |

Sasuyu Ubalat | Paiwan | Paiwan | The community’s efforts to educate kids the tribal values |

| 55 | 2017 |

Mountain Tribe, Sea Tribe 54 min/HD/2015 |

Etan Pavavalung | Paiwan | Paiwan; Amis | Environmental impacts on the artist Etan from the mountain and the artist Iyo from the seashore |

| 56 | 2017 |

Path of Destiny 71 min/HD/2017 |

Yang Chun-Kai | Han Chinese | Amis | The researcher Panay’s destiny becoming a Amis shaman sikawasay |

| 57 | 2017 |

Kalay Ngasan: Our Home 48 min/HD/2016 |

Huang Hao-Chieh | Atayal | Atayal | The elementary school teacher Wilang attempts to build a traditional Atayal house. |

| 58 | 2017 |

Dialogue Among Tribes |

Pan Zhi-Wei | Amis | Amis; Kavalan; Atayal |

Three urban migrants from different tribes returned home. |

| 59 | 2019 |

The Endurance to Become a Real Man 41 min/HD/2015 |

Uki Bauki | Kavalan | Puyuma | Men of Puyuma protested against moving their ancestral tomes for development |

| 60 | 2019 |

The Solemn Commitment to Palakuwan 84 min/HD/2017 |

Uki Bauki | Kavalan | Puyuma | Training boys to become men in the men’s house palakuwan |

| 61 | 2019 |

32 KM, 60 years 26 min/Digital 5D/2018 |

Laha Mebow | Atayal | Atayal | Following the elder Willang to search the tribal village’s roots |

| 62 | 2019 |

Muakai’s Wedding 60 min/Digital/2018 |

Su Hung-En | Toroko | Paiwan | The ancestral pillar Muakai at the museum of Taiwan University reunited with the villagers through a “wedding”. |

| 63 | 2019 |

Ciopihay: The Feather Headdress of Ceroh 56 min/Digital/2018 |

Fuday Ciyo | Amis | Amis | How to maintain the tradition of Ciopihay in the changing society? |

Figure 2 2017 TIEFF (The main character of Watan’s film, The Memory of Orality, was invited to talk after the screening.)

Figure 2 2017 TIEFF (The main character of Watan’s film, The Memory of Orality, was invited to talk after the screening.)

Ⅲ. Comparisons of Taiwan Indigenous People Documentaries by Indigenous and Han Chinese Directors

In order to highlight the vital perspectives brought to documentary filmmaking by indigenous directors, it is important to see how their motivations, purposes, topic selection, and ways of representation differ from those of non-indigenous directors. It is also important to consider what advantages they might have and what obstacles they might face.

To these ends, this section will draw comparisons of films made by three pairs of directors, with each pair consisting of one indigenous director and one Han Chinese director. The films analysed are: My River (2009) by Mayaw Biho and Amis Hip Hop (2007) by Futuru C. L. Tsai; And Deliver Us from Evil (2001) and Si Yabosokanen (2007) by Chang Shu-Lan (si Manirei) and Kawut Na Cinat’Kelang: Rowing the Big Assembled Boat (2009) by Lin Chien-Hsiang; Collected Ping-pu Memories (2011) by Bauki Pan Chao-Cheng and Returning Souls (2012) by Hu Tai-Li. In this analysis, the contributions of these films to anthropological theories and practices will be pointed out.

Mayaw Biho is perhaps the most prominent indigenous Taiwanese director. His culturally and politically significant documentaries have significantly influenced the indigenous social movement, and attempt to strengthen indigenous peoples’ identities and improve their living conditions. My River (2009, Figure 3), the follow-up to his first documentary Children in Heaven (1997), tells the ongoing story of children who lived with their migrant Amis parents below the Sanying Bridge in New Taipei City and these illegal houses were demolished by the government in Children in Heaven. After growing up, they moved to a rented apartment built by the government for indigenous migrants in Sanxia city, but eventually returned to the Sanying Bridge and rebuilt their simple houses. Again, they faced suppression by the authorities, and their houses were destroyed by bulldozers and large trucks. In My River, old images are shown to parallel the new ones. Why did these people return and rebuild their houses under the bridge? This film implies that, in the urban environment, they are searching for a lifestyle similar to that of a traditional Amis village, free and surrounded by soil and water. The song ‘Neither drunk nor sober, neither aching nor itching, neither shown nor seeing, neither dead nor living, am I not in Heaven?’ – performed by the famous indigenous singer Kimbo Hu – plays throughout Children in Heaven and My River. Mayaw Biho’s films show the contrast between the dreams of urban migrant indigenous people and the harsh realities they face. This film should inspire thoughtful consideration of the fact that, despite whatever economic forces may exist, urban indigenous migrants have cultural needs to be fulfilled.

Figure 3 Still Image from My River

Figure 3 Still Image from My River(Mayao Biho 2009, https://www.tieff.org/en/films/my-river/)

Futuru C. L. Tsai, a Han Chinese director and anthropologist, has long lived with the Amis Dulan villagers on the east coast of Taiwan and encouraged the revival of young men’s age-grade training in Dulan village. His ethnographic film, Amis Hip Hop (2007, Figure 4), depicts how the younger generation in the Amis Dulan age grade system created a particular Amis style of hip-hop and performed it at the tribe’s annual New Year Festival. Although this type of singing and dancing is criticised by external observers as being too modern and going against tradition, director Futuru C.L. Tsai discovers that the innovative Amis hip-hop actually follows the Amis tradition of performing in front of the tribal elders during the New Year Festival to please them. In addition, the young man who choreographs the Amis hip-hop performance inherited his talent for singing and dancing from his mother in the fashion of matrilineal Amis society. This film touches on the anthropological topic of the invention of tradition discussed in Hobsbawm & Ranger’s book (1983). With this film, Futuru C. L. Tsai challenges a traditional, more rigid view of what it means to revive and maintain tribal tradition, and shows that what appears exotic and modern might have traditional roots and meaning.

Figure 4 Still Image from Amis Hip Hop

Figure 4 Still Image from Amis Hip Hop(Futuru C. L. Tsai 2007, https://www.tieff.org/en/films/amis-hip-hop/)

Chang Shu-Lan (si-Manirei), a nurse from the Yami/Tao tribe on Orchid Island, learned how to create documentary films in order to facilitate her work. Her film And Deliver Us from Evil was selected as the closing film of the 2001 TIEFF. This film reveals the life of the sick Yami/Tao elders who live in separate houses, away from their families. This is because Orchid Islanders are very afraid of anito (the evil spirits) of the dead, which are believed to have become attached to these sick elders. As a nurse, Shu-Lan is responsible for the domestic care of these sick elders and encounters many difficulties. In the film, the audience can see that Shu-Lan has very close relationships with the elders, and seeks the help of Tao women who have converted to Christianity to help her care for them. After TIEFF’s screening of And Deliver Us from Evil, Shu-Lan was invited by many groups in different parts of Taiwan to screen the film and obtained financial support for the Elderly House Care Association of Orchid Island that she had founded.

At the 2007 TIEFF, Shu-Lan’s follow-up film Si Yabosokanen was selected. In this film, Shu-Lan tries to understand the elders’ thinking and attitudes towards living apart from their families. Do they feel that they have been abandoned by their children? She shows that the elderly have no complaints at all. They even express to the audience that they live alone for the health and benefit of their descendants. They only hope that their children can continue to supply meals for their survival. These elders are thus content with their simple and quiet living conditions.

With this film that shows these elders’ daily lives, Shu-Lan seeks to change the prejudiced views of outsiders (including many scholars) on the Tao tradition of separate housing for sick elders. Shu-Lan’s films thus provide the essential insider perspectives that explain this custom, previously considered ‘immoral’. In the discussion after the screening of each film, Shu-Lan told the audience explicitly: ‘We are not people without filial piety’.

Figure 5 Still Image from Si Yabosokanen

Figure 5 Still Image from Si Yabosokanen(Chang Shu-Lan 2007, https://www.tieff.org/en/films/si-yabosokanen/)

Lin Chien-Hsiang, the Han Chinese cinematographer of my film Voices of Orchid Island, later became a director and made the film Kawut Na Cinat’Kelang: Rowing the Big Assembled Boat (2009, Figure 6) on Orchid Island. His project, sponsored by Johnny Walker’s ‘Keep Walking Fund’, was very innovative. He attempts to cooperate with the Yami/Tao islanders to build an extra-large traditional boat with 14 rather than the typical 10 rowing seats, and then paddle this boat from Orchid Island to the shores of Taiwan. Lin Chien-Hsiang recorded the entire process and edited it into a documentary film. In the process, this project revealed how the modern Yami/Tao people must navigate their culture’s taboos in making a big carved boat for non-fishing purposes. This film shows how the crew participating in boat-building and paddling activities practice rituals to explain to the spirits about the modern situation and request pardon and protection. After completing the boat, they kill a pig in ritual sacrifice. The project and Lin Chien-Hsiang’s film create an unusual opportunity for researchers to observe the islanders’ rationale and the strategies with which they accommodate a changing society.

Figure 6 Still Image from Rowing the Big Assembled Boat

Figure 6 Still Image from Rowing the Big Assembled Boat(Lin Chien-Hsiang 2009, https://www.tieff.org/en/films/kawut-na-cinatkelang/)

The Kavalan director Bauki Pan Chao-Cheng’s film Collected Ping-pu Memories: On Representing Kavalan and Ketagalan Voices and Images (screened at TIEFF in 2011) is the result of a collaboration with Hu Chia-Yu, professor of Anthropology at National Taiwan University. Professor Hu assembles Kavalan and Ketagalan sounds, photographs, and 16 mm films recorded during the Japanese colonial period and stored at the anthropological archives of National Taiwan University and the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. Director Pan, teaching at Tze Chi University, discovered his Kavalan identity later in life. He completed several documentary films on Kavalan history and current conditions. Both Hu and Pan believe that making a film to show the forgotten sounds and images and their interaction with the Kavalan and Ketagalan descendants would have a significant impact on cultural revitalisation. Indeed, scenes in this film, such as when the elder of the nearly extinct Ketagalan tribe hears the voice of his ancestor and anxiously asks for a copy of the tape for conservation and teaching, are very touching. Pan also presents images of Kavalan’s ancestral worship rituals, banana silk weaving practice, and the name rectification movement to gain official recognition as a tribe in 2002. In a dialogue between Hu Chia-Yu and myself, published in Man and Culture (Renlei yu wenhua), Professor Hu says, as a producer of this film: ‘In Collected Ping-pu Memories (Figure 7), I seek to present, through the film, relics of the Ping-pu past, so that everyone in the tribe can see these relics, and have their memories quickened, their passion for their community rekindled’ (Hu and Hu 2012).

My own film Returning Souls (2012), deals with an anthropological museum and an indigenous tribe. In 2003, several young people from Tafalong village visited the museum of the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, and discussed the possibility of returning the sculpted ancestral wooden pillars of Tafalong’s Kakita’an house to the tribe. These carved pillars depict Tafalong legends such as the great flood, the glowing girl, the descending shaman sent by the mother sun, and the father-killing headhunting event that initiated the most important head-hunting and new year Ilisin ceremony. The Kakita’an family living in the house related to head-hunting rituals was forced by the Japanese colonial government to move out after the head-hunting Wushe Incident in 1930, however, the Japanese government converted the house into an exhibition site in 1935. During the Nationalist Chinese rule, the Kakita’an house was toppled by a large typhoon in 1958. A researcher from the Institute of Ethnology discovered the carved pillars on the ground and moved them to the Institute’s museum in Taipei. As a research fellow at the Institute of Ethnology, I followed the development of this case and eventually made a documentary about it.

Figure 7 Still Image from Collected Ping-Pu Memories

Figure 7 Still Image from Collected Ping-Pu Memories(Bauki Pan Chao Cheng 2011, https://www.tieff.org/en/films/collected-ping-pu-memories-on-representing-kavalan-and-ketagalan-voices-and-images/)

As the film shows, with the help of Tafalong shamans who saw ancestors attached to the carved pillars, the descendants of the Kakita’an family, along with young tribe members and concerned villagers performed rituals at the museum, and brought their ancestors’ souls back to Tafalong village rather than the pillars themselves. They then began to reconstruct the Kakita’an house. In this film, I reveal that in an environment highly influenced by Western religions, national land policy, and local politics, young Tafalong people’s dream to revitalise their culture and bring back not only their ancestors’ souls but also the soul of the village encountered many obstacles.

Many screenings of Returning Souls in different indigenous tribes, university classrooms, film festivals in Taiwan, and abroad (especially in a 2014 tour of the US) provided direct contact and discussions with audiences. Through the film, audiences could feel that in the eyes of shamans and the villagers, the carved pillars are not artefacts for display, but objects linked to the souls of their ancestors. In her review of Returning Souls, Kate Hennessy (2013: 140, 142) states:

Returning Souls is an intricate portrait of indigenous Taiwanese cultural revival and postcolonial negotiation of identity, religion, and the politics involved in the ‘return’ of cultural heritage to its place of origin.... Returning Souls also makes visible a spectrum of elements of intangible cultural expression that reconnection to tangible cultural heritage can facilitate. Returning Souls represents an important contribution to the increasingly intertwined disciplines of museum, media, and visual anthropology.

Figure 8 Still Image from Returning Souls

Figure 8 Still Image from Returning Souls(Hu Tai-Li 2012, https://www.tieff.org/en/films/returning-souls/)

In addition to the film Returning Souls (Figure 8), I wrote an article (2017) that provided more historical materials and field collected data to give a detailed description and analysis of this unique ‘repatriation’ case. But only through the film, the audience could get vivid impressions of the Tafalong villagers’ emotions and concerns in the processes of reconstructing the Kakita’an house.

By considering these representative films, some common characteristics of films made by Taiwan’s indigenous directors can be observed. Like advocators, the indigenous directors produced documentaries with political and cultural purposes, such as protesting injustice, erasing stigmas, enhancing indigenous identity, recalling memories, and stimulating cultural revitalisation. The presence in these films of ‘cultural activism’ (Ginsburg 1993; 1997) is a characteristic shared with indigenous media in other parts of the world, such as that of Native Americans (Prins 2002), aboriginal Australians (Ginsburg 2002), and Amazonian Kayapo (Turner 2002).

Taiwan’s indigenous directors’ intimate attachments to the tribes and the indigenous issues of the nation are advantageous in making powerful and infectious films. However, documentary films made by Taiwanese indigenous directors also exhibit some seldom-mentioned blind spots and problematic aspects. While they focus on revealing and criticising external wrongdoings, they intentionally avoid and hide internal conflicts and problems in order to protect the positive public perception of indigenous peoples. Despite Chang Shu-Lan (si-Manirei)’s worries of the outsiders’ negative impressions of the Yami/Tao people and efforts to correct them with her films, Mayaw Biho admits (2013) that as an indigenous director, it is very difficult to mention and criticise the weaknesses of the indigenous people in his films. Bauki Pan Chao-Cheng states in an interview (2009), “My motivations and purposes to make documentaries are to tell the public that we Kavalan people have not disappeared, and still keep some histories, rituals and customs. I should not talk about Kavalan people’s internal disputes and inconsistency in my films”.

Without such heavy burdens, when Han Chinese directors who have long-term and close connections with indigenous groups make documentaries, their films can provide more insights and reflections that are equally valuable to the development of indigenous societies.

IIn this article, I have briefly reviewed the birth and main characteristics of TIEFF from 2001 to 2019, as well as the rise of indigenous people documentaries in Taiwan. I have also compared six indigenous people documentaries made by either indigenous directors or Han Chinese directors, and pointed out the advantages and disadvantages of the approach indigenous directors bring to their documentaries. I hope that the development of TIEFF, along with indigenous people documentaries and visual anthropology in Taiwan, can contribute to Taiwanese society and be seen by the rest of the world.

References

- Chiu, Kui-fen

- 2007

- The Vision of Taiwan New Documentary. In Darrell William Davis and Ru-shou Robert Chen (eds.)

Cinema Taiwan: Politics, Popularity, and State of the Arts, pp.35–50. London: Routledge.

- Davis, D. W. and R. Robert Chen (eds.)

- 2007

- Cinema Taiwan: Politics, Popularity and State of the Arts. London: Routledge.

- Ginsburg, Faye D.

- 1993

- Aboriginal Media and the Australian Imaginary. Public Culture 5 (3): 557–578.

- 1997

- “From Little Things, Big Things Grow”: Indigenous Media and Cultural Activism. In R. Fox and O. Starn (eds.) Between Resistance and Revolution Cultural Politics and Social Protest, pp.118–144. London: Routledge.

- 2002

- Screen Memories: Resignifying the Traditional in Indigenous Media. In Faye D. Ginsburg, Lila Abu-Lughod, and Brian Larkin (eds.) Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain, pp.39–57. Berkeley: University of Berkeley Press.

- Hennessy, K.

- 2013

- Returning Souls by Hu Tai-Li. American Anthropologist 115 (1): 140–142.

- Hobsbawm, E. and T. Ranger (eds.)

- 1983

- The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hu, Chia-Yu 胡家瑜 and Hu, Tai-Li 胡台麗

- 2012

- The Two Hus in Dialogue: Discussing Anthropology and Film through Returning Souls and Collected Ping-pu Memories: On Representing Kavalan and Ketagalan Voices and Images. 雙胡對談 :從《讓靈魂回 家》與《收藏的平埔記憶 :再現噶瑪蘭與凱達格蘭身影》談人類學與電影. Renlei yu wenhua 人類與文化 43: 38–51.

- Hu, Tai-Li 胡台麗

- 2013

- The Development of “Indigenous People Documentaries” in Early Twenty-first Century Taiwan and the Concern with “Tradition”. Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 39 (1): 149–160.

- 2017

- The Reconstruction of the Kakita’an Ancestral House in Amis Tafalong Village: Reflections on the Repatriation of “Artefacts” and the Revitalization of “Traditions”. In Hu Tai-li, Yu Shuenn-Der and Jou Yuh-Huey (eds.) Crossing Cultures: Anthropological and Psychological Visions, pp.1–40. Taipei: Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica. 阿美族太巴塱 Kakita’an 祖屋重建 :「文物」歸還與「傳統」復振的反思。 刊於 跨・文化 :人類學與心理學的視野。胡台麗、余舜德、周玉慧主編。頁 1–40。台北 :中央研究院民族學研究所。

- Lee, Daw-Ming 李道明

- 1994

- Representations of Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan in Films and on Television In the Past One Hundred Years. 近一百年來台灣電影及電視對台灣原住民的呈現. Dianying xinshang 電影欣賞 69: 55–64.

- Lin, Wen-Ling 林文玲

- 2001

- Rice Wine Plus Salt: Indigenous Films’ Politics of Representation. 米酒加鹽巴 :「原住民影片」 的再現政治. Taiwan: A Radical Quarterly In Social Studies 台灣社會研究季刊 43: 197–234.

- 2003

- Taiwan Indigenous Films: Transforming Techniques of Cultural Inscription. 台灣原住民影片 :轉化中的文化刻寫技術. Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology 考古人類學刊 61: 145–176.

- 2005

- The Series Films ‘What Is Your Real Name’ and Indigenous Image-Action Movement 翻轉漢人姓名意像 : 「請問『蕃』名」 系列影片與原住民影像運動. Taiwan: A Radical Quarterly in Social Studies 台灣社會研究季刊 58: 85–134.

- Mayaw Biho 馬躍・比吼

- 2013

- Mayaw Biho: A Speech on Contemporary Taiwan Indigenous Documentaries. 馬躍・比吼 :當代臺灣原住民族紀錄片系列演講( 15 分鐘版)。 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FQQtIaRW2M0 (accessed January 14, 2021)

- Prins, H.E.L.

- 2002

- Visual Media and the Primitivist Perplex: Colonial Fantasies, Indigenous Imagination, and Advocacy in North America. In Faye D. Ginsburg, Lila Abu-Lughod, and Brian Larkin (eds.) Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain, pp.58–74. Berkeley: University of Berkeley Press.

- Taiwan International Ethnographic Film Festival (TIEFF) Official Website

- 2001

- 台灣國際民族誌影展官網 https://www.tieff.org/en/ (including information on past TIEFF selected films)

- Turner, T.

- 2002

- Representation, Politics, and Cultural Imagination in Indigenous Video: General Points and Kayapo Examples. In Faye D. Ginsburg, Lila Abu-Lughod, and Brian Larkin (eds.) Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain, pp.75–89. Berkeley: University of Berkeley Press.

- Wu, Chen-Mei 巫正梅

- 2002

- An interview with Bauki Pan Chao-Cheng. Taiwan Indigenous Artists Website. 潘朝成(木枝・籠爻)訪談錄・ 台灣原住民族文學家與藝術家網頁。 http://portal.tacp.gov.tw/litterateur/portrait/51709 (accessed January 14, 2021)

Selected Films

- Bauki Pan Chao-Cheng 潘朝成 (dir.)

- 2011

- Collected Ping-pu Memories: On Representing Kavalan and Ketagalan Voices and Images 收藏的平埔記憶 : 再現噶瑪蘭與凱達格蘭聲影. Produced by National Taiwan University Press 國立台灣大學出版中心. https://www.tieff.org/en/films/collected-ping-pu-memories-on-representing-kavalan-and-ketagalan-voices-and-images/ (includes a clip of the film) (accessed January 14, 2021)

- Chang, Shu-Lan (si Manirei) 張淑蘭 (dir.)

- 2001

- And Deliver Us from Evil 面對惡靈. Produced by Chang, Shu-Lan. https://www.tieff.org/en/films/and-deliver-us-from-evil/ (includes a clip of the film) (accessed January 14, 2021)

- 2007

- Si Yabosokanen. Produced by Chang, Shu-Lan. https://www.tieff.org/en/films/si-yabosokanen/ (includes a clip of the film) (accessed January 14, 2021)

- Hu, Tai-Li 胡台麗 (dir.)

- 2012

- Returning Souls 讓靈魂回家. Produced by Hu Tai-Li; Distributed by Documentary Educational Resources (English version) and Tosee Culture 同喜文化 (Chinese version). https://www.tieff.org/en/films/returning-souls/ (includes a clip of the film) (accessed January 14, 2021)

- Lin, Chien-Hsiang 林建享 (dir.)

- 2009

- Kawut Na Cinat’Kelang: Rowing the Big Assembled Boat 划大船. Produced by Together Studio 我們工作室. https://www.tieff.org/en/films/kawut-na-cinatkelang/ (includes a clip of the film) (accessed January 14, 2021)

- Mayaw Biho 馬躍・比吼 (dir.)

- 2009

- My River 我家門前有大河. Produced by Taiwan Public Television 公共電視文化事業基金會. https://www.tieff.org/en/films/my-river/ (includes a clip of the film) (accessed January 14, 2021)

- Futuru C. L. Tsai 蔡政良 (dir.)

- 2007

- Amis Hip Hop 阿美嘻哈. Produced by Futuru C. L. Tsai. https://www.tieff.org/en/films/amis-hip-hop/ (includes a clip of the film) (accessed January 14, 2021)