Doing Visual Anthropology in Northern Cameroon: Sharing Stories/Histories through Dialogue

(Published March 27, 2024)

Hello, Dr. Mouadjamou Ahmadou. It has been a long time since we met at the conference at the National Museum of Ethnology, Japan, in 2017.

I know that you often travel internationally, as a judge for film festivals, a visiting lecturer, and of course as an active fieldworker.

Yes, I just returned to Cameroon from France as I was invited to the African Film Festival, "Afriques en Vision" and I have worked with my French colleagues from CNRS and MSH Mondes on the new film shot in Chad and edited in Nanterre University.

It is my pleasure to share my knowledge and experience as much as I can. The practice of visual anthropology in northern Cameroon can be explained gradually from its onset till date.

It all began with a collaboration between Norwegian and Cameroonian visual anthropologists and the creation of universities in northern Cameroon. Most of the students, teachers, and researchers’ work does not only contribute to the understanding of lifestyles, but also provides opportunities for practitioners of this discipline to highlight their local concerns and let information circulate. Meanwhile, a work full of reflexivity and sometimes subjectivity does not prevent the audience from detecting the lapses of contradiction.

The status of audiovisual production in the public and daily life of the population of Northern Cameroon is important in more than one way and is rich in lessons. More than 60 films were produced and are currently available for intellectual consumption. Their contribution to scientific research, their use in the valorisation of research results, and the acquisition of technical skills are large-scale contributions that the practice of visual anthropology serves to a curious world.

Training in anthropological cinema results from the desire for a long-term collaboration between Cameroon and Norway. Encouraged by Professor Emerita Lisbet Holtedahl, whose research field in Niger was oriented by Jean Rouch, left her bag in the North of Cameroon in the 1980s. She made films for about 30 years and published texts which shed light on and facilitated the understanding of the lifestyles of societies in Northern Cameroon. Through these networks, several students and cinema practitioners have produced knowledge that returns to us.

She also trained, from 1993 to 2023, teachers and researchers specialising in visual anthropology at the global level. This success created a huge network that connects former students and trainers in visual anthropology.

Below is a picture of her and her first visual anthropology PhD student on his public defense at the University of Maroua, Cameroon in 2020.

Lisbet is currently a Professor Emerita at the Master’s program in visual anthropology at the University of Tromsø, Norway. She continued to work on materials collected in Africa and Norway throughout her academic career and travelled to Cameroon every year. She has been working in Ngaoundéré, Northern Cameroon, since 1982.

The creation of visual anthropology courses in Cameroonian universities has enabled students to enrich their range of methods of investigation and the restitution of social science research results. Students at the Bachelor and Master’s levels in visual anthropology and social sciences are generally familiar with consulting and developing audiovisual content as part of their regular routine in classrooms, festivals, television, cinemas and social networks.

However, they do not sufficiently use these skills in their scientific production even though their research topics often are relevant to them. This situation can be accounted for the unavailability of screening venues and scarcity of festivals.

Since 2022, we have registered international Master students from Chad, Niger, Mali and Cameroon at the University of Maroua.

The paradox is even more obvious because the disciplines of visual anthropology and documentary films have created classical job opportunities in Cameroon; a few renowned films have been made. The technological evolution has facilitated the designing of audiovisual content, which is often used without full awareness. It is time to engage in a fruitful reflection on film practice among young social scientists to quickly put the research apparatus at their disposal.

Of course. Here I can show you some films and trailers with the URL for more information.

Firstly, I will send you a couple of films about the similar issue of drugs in a community.

One is by Atouna Michel called “Happier Than a Millionaire” (2019).

Full-length film URL: https://site.uit.no/viscam/2020/11/20/happier-than-a-millionaire/

Next is by Lankissa Tizi Pierre called “Scrap is Our Future” (2020).

Full-length film URL: https://site.uit.no/viscam/2020/11/19/scrap-is-our-future/

Yes, it is a concerning issue that we all have to be aware here.

The third one I want to show you is by Hamadama Aboubakar, called “Cock Diagnosis” (2021). It is about the traditional doctor in Northern Cameroon.

Full-length film URL: https://site.uit.no/viscam/yiga-kaka-cock-diagnosis/

The fourth one is “We have All We Need” (2023) by Tchoupno Ndjidda. It is about the local project for malnutrition issues.

Full-length film URL: https://vimeo.com/919807248

Finally, I would like to add 2 films from our female students Ldouma Rebecca and Doba Kadana.

You can watch their full-length films from the URL below.

“Change of Perspective, Change of Life” (2020) by Ldouma Rebecca:

https://site.uit.no/viscam/2021/06/06/change-of-perspective/

“Daouda, the Shoemaker” (2020) by Doba Kadana:

https://site.uit.no/viscam/2021/06/06/i-chose-the-shoes/

Yes, exactly. It was the same for me and it made a huge impact on my life.

Let me show you my Master’s degree film “Zavra, a passer in Kapsiki land” (2004) which was realized as a part of our collaboration with Norway.

Full-length film URL: https://nafafilm.org/?q=node/425

The Ngaoundéré Anthropos Programme was the first project to pioneer the practice of visual anthropology in Northern Cameroon. This is how the Norway/Northern Cameroon cooperation and mirroring between their social science practitioners was born.

It all started in 1993 with the establishment of the Ngaoundéré Anthropos Programme at the University of Ngaoundéré in Northern Cameroon. The Program aimed to develop academic skills in Northern Cameroon, a region which was separated from academic and cultural institutions in the south of the country due to its geopolitical characteristics. At the time of the creation of the Ngaoundéré Anthropos, no published works on the people and cultures of Northern Cameroon were available in the northern regions. In addition, none was written by the indigenous people of Northern Cameroon.

The program played a crucial role in establishing social sciences in Cameroon, even after it was completed in 2006. Many academics who received Anthropos scholarships had been recruited from the University of Ngaoundéré to the University of Maroua, which became the second largest university in Cameroon in 2008.

Another major contribution of the collaborative activities between Ngaoundéré and Tromsø within the framework of that program was the designing of the Master’s Program in Visual Anthropology at the University of Tromsø. Important Anthropos collaborators included Eldridge Mohammadou, Oumaru Nduudi, Mohammadou Djingui, Aliou Mohammadou and Hamadjoda Gabriel contributed to set the branch.

We had the VISCAM Project (2017-2021) that was a continuation of the Ngaoundéré Anthropos Programme. It was spread over a period of 5 years and connected two Cameroonian universities (Ngaoundéré and Maroua) with the University of Tromsø in Norway.

The VISCAM Project contributed to the publication of the first work on visual anthropology in Africa, which reviewed the evolution of the sector in Cameroon between 1993 and 2021. This work is part of the achievements of the VISCAM Project, a teaching, research and academic mobility program in visual anthropology. More than a decade after the third phase of the Ngaoundéré Anthropos Programme, it is structured around research on innovative themes and emerging cinematographic practices in social science research, particularly visual anthropology, in Northern Cameroon and Northern Norway. It contributes to develop human resources and build several collaborations with institutions and among the researchers or among the visual anthropology laboratories.

In 2018, I took part in the “Minpaku info-forum museum” on the renaissance of Cameroonian ethnographic objects. There, I met visual anthropologist colleagues with whom we developed a fruitful exchange in the organization of communications between the visual anthropology laboratory of the University of Maroua and Anthro Lab of Japan. Several students and colleagues carried out the screening-debates by presenting their research results. This interaction produced an enrichment of the exchanges which generated integrations that we mobilized in our laboratories.

These are the pictures of the international meetings.

Starting in 2017 with an agreement linking the three universities mentioned above, this project, whose field of interest relates to the use of audiovisual tools and data in anthropological research, aimed to develop education and sustainable training in visual anthropology while striving for academic excellence on questions and problems related to peace and the pursuit of well-being. It has supported the production of a multitude of research works (master’s and doctorate degrees) and ethnographic films on various social, cultural and economic issues in developing countries.

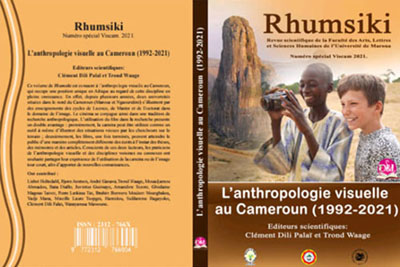

The first proceedings were published in the non-thematic issue of the journal Rhumsiki in 2021 as part of the VISCAM Project. Their analyses primarily focused on methodological and epistemological questions related to anthropological practice during field surveys.

This book was entitled Visual Anthropology in Cameroon, from 1992 to 2021 and edited by Clément Dili Palaï and Trond Waage. Obviously, it provided insight into the analysis of investigation techniques and the place of the camera in the research practices of visual anthropologists on the one hand; those of social science researchers on the other hand. In doing so, the work emphasises the impact of audiovisual data on capturing ethnographic facts. A special issue of the Journal of Anthropological Films, as well as ten films by student scholarship recipients of the project, will be edited and produced in the same vein.

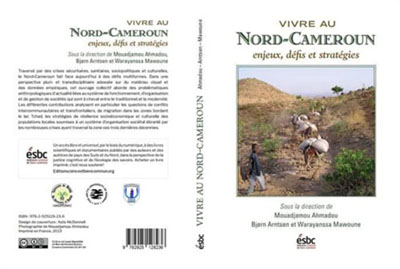

Two years after the publication of this pioneering work in Africa dedicated to visual anthropology, a second publication, coordinated by a transdisciplinary team (Mouadjamou Ahmadou, Bjørn Arntsen and Warayanssa Mawoune), endeavoured to present the results of the work carried out within the framework of the VISCAM Project. The analyses carried out are based not only on audiovisual material and ethnographic films produced by the students and researchers involved in the project, but they are also interested in new issues and challenges linked to the various crises (health and security) which punctuate the daily lives of populations and have troubled North Cameroon for almost a decade.

Living in North Cameroon: Issues, challenges and strategies examined the factors, actors, and consequences of crises, social changes and socioeconomic dynamics of the populations in the northern parts of Cameroon. It also exposed the resilience strategies (social, economic, political and cultural) of a cosmopolitan area, where the traditions and daily actions of populations adapt to the environmental hazards of their time.

I have noticed in the publications that the focus is, in the first work, on questions of methodology and epistemology. The second is an analysis of social and economic life in Northern Cameroon. On this basis, what do you think of the contribution of this work within the framework of the VISCAM Project to the field of anthropology?

The contribution of this work to the epistemological field of visual anthropology in Africa and Cameroon is invaluable in view of the data collected and analysed by the various contributors who rely, for the most part, on anthropological methodological practices involving the role of the visual and the image in a broad sense in the phenomenology and understanding of cultural and ethnographic facts specific to Northern Cameroon. Its added value also lies in addressing current issues concerning the challenges of daily living and the strategies that people develop to ameliorate their living conditions. This highlights the systems of hierarchy and value in full change and allows the continual questioning of a discipline in full construction in southern universities.

The research work was evaluated by a multidisciplinary international team that collaborated and complemented each other.

In 2022, the Sahel on Sahel Project was launched in Maroua. There is a novelty in its operationalisation: the mobility of Niger students towards Maroua as part of their Master’s and PhD studies. Several films dealing with dialogue and conviviality will be produced by doctoral students under the supervision of visual anthropologists at the University of Maroua. More than 30 films have been made on the various subjects in the far north province in collaboration with the local communities.

Since July 2023, the University of Ngaoundéré has followed and four field research teams have been formed. Surveys were carried out in the Belaka district (two teams), Lake Dang (one team), and Repyamga district (one team) to examine such varied issues as intergenerational communication and the integration of internally displaced persons who are victims of kidnapping and scarcity of fishery resources.

The first team addresses the issue of education of young Mbum in the urban milieu in the Belaka quarter in Ngaoundéré – in a context marked by modernity, the way young people were educated and had to adapt the context. The new generation is gradually taking over from the old.

As indicated by the results, the two teams were expected to have at least four films, since it was stipulated that ten days were allowed for investigations and data collection and ten days for editing, but due to some administrative and light problems, they did not meet the objectives. The work is continuing. The students and supervisors are working hard to refix the issue and get films ready.

Finally, to improve on the next fieldwork, it is necessary to set clear goals for: hold regular meetings with team members to ensure that everyone is at the same level; consider multiple points of view instead of just one’s own; motivate project team members; let your project team know that you trust their abilities which will make them more productive and creative; and focus on completion and quality or perfection.

I should also mention that the other two teams were first deployed on two sites.

The first theme was research on Fulani refugees who left their villages to settle in the city of Ngaoundéré in Rep-Yanga district. It should be noted that the entire neighbourhood is composed by the Fulani who have fled the bush because of ever-increasing insecurity.

The second theme was entitled Climate Change and Rarefied Resources: Lake Dang. In this film, the directors show the impact of human activities around the lake and their consequences on the scarcity of fisheries resources in the lake. As part of this film, they were asked to carry out observations of the activities around the lake.

From Jean Rouch to us, many achievements have been made in the field of documentary cinema. We have moved from the comparative perspective, where we have been studied by foreign anthropologists to the cross-cultural perspective that stipulates that people anthropologically look at each other and talk to each other. Nowadays, as visual anthropology is developing, and Africans are changing positions: from in front of the camera to behind the camera; the discourse is dynamic and alternating. The first cohort of visual anthropologists’ students carried out Africa based research. They did their fieldworks in their own societies. Some studied their own families.

As it is said that anthropology is a meeting science where people move to study other people. The first cohort worked to promote their cultures, to defend some point of view through filmmaking and to achieve goals among which getting their diplomas. Then, the second cohort brought novelty by investigating the others. Increasingly, the view became more global when collaborations enabled Africans to explore the lifestyles of European societies through filmmaking in Scandinavia and specifically in Northern Norway. Nowadays, several African anthropologists, students and even researchers are doing fieldwork in various foreign countries in Africa and beyond. Visual anthropology in Africa is connected to a global world.

Thank you for sharing your valuable “oral history” about the past, present and future of the visual anthropology scene in Northern Cameroon, through this “social media-like” dialogues.

It is a pure surprise and excitement to know the practices and evolvement of visual anthropology in Africa through the collaborations with Norway.