This article examines the social dynamics provoked by filmmaking as a primary engagement during fieldwork and how camera-based interventions can be meaningful for qualitative research. Conceptualizing the camera as a catalyst that fundamentally shapes the ethnographic encounter, the author attends to what the presence of the camera inspires and not solely to what it records. Making reference to the author’s ethnographic research on memory practices in post-war Peru, the article contends that the circumstances and conditions of making people’s stories visible, and the practice of giving these stories aesthetic and narrative form, are essential to developing a theoretical argument. In other words, as social scientists, there is a point to be made about critically reflecting on the discourses and frameworks that enable or disable camera-based storytelling practices that are not solely epistemological but fundamentally political.

Key Words visual anthropology, camera-based research, collaborative filmmaking, visibility, visuality

The Politics of Visibility and Visuality in Camera-Based Research

(Published March 31, 2023)

Abstract

Picture yourself in the middle of a protest. You are one of the protesters, and the streets are full of people who shout just as loud as you do. You are there because of an injustice that was done to you and your family. However, this injustice does not exist for the government of your country, and little has been done to alleviate the pain you and your family endured over decades. This is why you are standing in the middle of the crowd and voicing your demands with all your might.

Now, picture yourself in that crowd while accompanied by a person holding a camera filming you. The lens’s gaze follows you and nurtures your responses. How does it feel? Are you comfortable, intimidated, or empowered? What do you imagine that a person with a camera is doing for you and your cause? What is at stake, both for you and them?1)

Now, picture yourself as the person with the camera following one of the protesters whose story you know intimately. You did not experience this injustice, but you feel their anger and frustration almost as if it were your own. Knowing this person and their story, you are invested in their cause. You point the camera at people’s faces, record their piercing words, their tensed-up bodies to show what you are sensing in the crowd, and amplify their calls for justice with and through the camera. You are immersed in the action, and imagining what your recorded image could do to help the person you have come to know and all other people in a similar situation.

What gives form to the image is the encounter through the camera that is fundamentally shaped by the relationships between people, places and ideas.

This exercise is inspired by what I experienced filming with victim-survivors of the Peruvian internal armed conflict (1980–2000), who, at the time, were calling for their relatives to be exhumed from one of the 5,000 mass graves still scattered around the country. Between 2012 and 2015, I conducted a camera-based collaborative research project with actors in the conflict, including victim-survivors, former insurgents, and ex-members of the military, to understand the social dynamics of a polarized memory discourse. Working with a diverse set of people who had experienced each other as enemies, the task was to create images, sounds, and words that were loyal to their stories yet without compromising what we now know of the conflict’s history. The ethical conundrums that arose from this intervention forced me to think hard about how collaborative filmmaking could contribute to the ethnographic exploration of post-conflict memory and its politically contentious discourse. What can audiovisual storytelling express in such circumstances beyond its literal content? How can a reflection on the storytelling process of a collaborative, co-creative film project offer a way to explore the political fields in which stories emerge?

As Darcy Alexandra put it in her work with asylum seekers in Northern Ireland, the co-creative process is “a means of engaged inquiry through media practice facilitating voice and listening about issues that research participants determined through the stories they selected, the artefacts they created, and the exploratory and contextualizing dialogue that developed over the course of our collaboration”. (Alexandra 2019: 129) Co-developing my research partner’s stories and audiovisual scripts, the making of the film “Between Memories” (2015) revealed how a tense political landscape mobilizes practices of remembering the conflict exposing the boundaries and limitations of a discourse that fundamentally and often-violently shapes the stories people tell. And yet they are the stories people have built their lives on after the conflict, as victims, survivors, heroes, and perpetrators, and shaped the communities where they now feel they belong. For this reason alone, these stories need careful consideration when navigating claims of truth, affects, and personal relationships.

When conducting camera-based research, the central concepts emerging, especially in politically contentious fields, are those of visibility and visuality. The route to delineate what can be made visible and how, is paved by the choices made in the process of producing a story. Here, visibility constitutes the social framing of audiovisual storytelling, while audio-visuality refers to the relationship between an aesthetic form and its specific social meanings. When treading the thin line between visibility and invisibility or between potential audiovisual forms, the role of the camera is limited because recording only takes place after the narrator and researcher have negotiated what can be filmed. Nonetheless, the camera and all its attached meanings can be understood as the catalyst that sets in motion this epistemologically valuable decision-making process. In this sense, research spans way beyond the recording button: questions arising from the presence of the camera, ambiguous engagements and relationships, aesthetic approaches, creative ideas, contradicting agendas, and unevenly distributed agencies shape the process and its outcome.

In this article, I argue that a camera-based investigative approach needs to incorporate an analytical consideration for storytelling processes (context and the creation of form) that results in the story or content we end up seeing on screen, as well as its practice of sharing reflections on its final outcome (between researcher, research partners, and audiences), for instance, after screenings. If making a film is at the core of a research project, the research process does not necessarily end with the last bit of recording or the final edit. Once a film is concluded, traveling between contexts and contributing to discourses, the relationships between filmmakers and research partners gain a new dimension, namely, that of their film’s reception. Conversations turn from creative (What are we doing?) to reflexive (What have we done?). The experience or vision of a film’s public life is as epistemologically meaningful to the research endeavor as the process of making the film because it allows for this layer of post-fieldwork reflection to be shared between collaborators and potentially included in writings that build on the experience of co-creative filmmaking.

With this, I want to offer a response to the doubts many filmmaking students and researchers have voiced about incorporating the filmmaking and film-viewing process into their analysis beyond the anecdotal. First, this material, either on tape or as notes, is fundamental to the investigative process since it establishes a field that extends from the protagonists into a broader community or society. Second, the camera is a catalyst, not just for the social relationships it records but also for the social dynamics it elicits.

The Camera as a Catalyst: On Encounters and Relationships

Coming back to the introductory exercise, imagining what drives our different engagements with the camera establishes our mise-en-scène: the camera is (only) what we make of it. It is a technological device that does not do anything unless picked up for a reason, whatever the reason may be. All interpretations of, associations with, or expectations towards the device about its role and impact come from some kind of experience or idea. Once a camera is picked up, it becomes an agent provocateur, mobilizing its various meanings. Its presence provokes action through the act of looking at, being looked at, hearing, or being heard. In our introductory exercise, the affective relationship was the driving force on both sides of the lens and microphone. How we speak and perform as filmmakers and filmed is intensified by the notion of a “present public”. This example was of a street protest, but the same would apply if we were seated with our research partners in a living room looking at family photographs or being shown how to bake bread in a traditional oven. A technologically facilitated gaze before a present public, an audiovisual record, a retrievable memory of time, place, and person(s) ceases to be “just” about the moment. It extends one’s experience of the moment to an imagined audience in a format that is infinitely reproducible, potentially anywhere. The anthropologist and filmmaker Jean Rouch (Rouch 2003) made a point in understanding the performance of a camera, not as distortions or false representations of the world. To him, it was the world itself that was transformed by the cinematographic process and presence of the camera (Henley 2010: 6). This provocation of performances applies not only to the people being filmed but also to those filming. Pointing the gaze, framing, and moving in space are practices that articulate social dynamics and what is at stake—not much for some and the world for others.

According to Hannah Arendt, subjectivities are constantly negotiated through actions. Action, she argues, is “revelatory” in that the person engaging in action discloses their essential being to others (Arendt 1958: 180). In this space, in-between subjectivities, “private and public interests are always problematically in play” (Jackson 2005). The camera facilitates and expresses people’s negotiations regarding what can or cannot be made visible and how. The presence of the camera and microphone alters the atmosphere in a way that is attuned to the situation in which the filmmaker and the filmed meet. In this way, even awkward, odd, or seemingly imposed performances with or in front of the camera are indicators of the encounter and part of a bigger picture. There is another dimension to this encounter, which both shapes and is shaped by the moment. The relationship between filmmaker and filmed can have a multiplicity of histories that influence the encounter, infusing trust, ease, affection, or opposites. How long filmmakers and the filmed have known each other, as well as their alliances, will inevitably define how they relate with and before the camera. The question remains as to how considerations of this interplay between subjectivities through technology impacts the ways ethnographers engage analytically with the realities they encounter. How these dynamics produced by the camera can be turned into “data”.

Truth Matters (to the Storyteller and their Audience)

Before we turn to what is “analyzable” in camera-based research, there is something to be said about the dynamics that image (and sound) production evoke among people who have experienced injustices during violent conflicts. These dynamics relate to the desire or urge to render one’s story real or true through the process of visibilization. Truth and storytelling, particularly after violent conflicts, have a long and tense relationship (Antze and Lambek 1996). Truth is important not only for those who have suffered injustices (Clarke and Goodale 2010; Kesselring 2017, Dietrich 2019) but also for their audience. Stories must be experienced as honest to be believable. This is not merely a matter of personal significance. Public acknowledgment of their experiences as true allows victim survivors access to transitional or criminal justice, but more importantly, it enables the possibility of personal closure and societal healing, which are the basis of any reconciliatory effort (Eltringham 2021). However, memory is not always about truth but rather about truth-telling (Milton 2014). Memory has no specific agenda since it can be about remembering as much as forgetting (Radstone and Schwarz 2010: 3). In post-conflict settings, memory work highlights the articulation of truth more than the integrity of the stories. It is the sum of its parts—the collages made of stories told and heard—that enables individuals and the collective to heal (Milton 2014: 41). However, memory cannot exist without truths. What is the impact on discourse about memory when people’s claim to truth is lessened for the sake of everybody speaking? Would the (partial) resignation of truth not defy the purpose of truth-telling altogether? These tensions between truth and memory cannot be evaded but have to be considered, perhaps even more so when producing stories with images that are specific to people and places.

When research partners lay literal claims to truth, they do so through content or “what is being said”. However, it is often not within the researcher’s capacity to verify these literal truths. Neither should this be their intention since it can only lead to either relativizing incommensurable accounts or bias. What researchers can do, however, is to look for truth in storytelling practices rather than in stories that can exist in isolation. To tell stories, audiovisual storytellers must engage their surroundings and enter conversations with people, objects, and landscapes. An analysis of such practices inevitably involves an examination of their (im)possibilities and limitations.

For a storytelling project to work within a polarized memory landscape that continues to inflict violence on people by creating the circumstances and conditions that force them to mute or mutilate their stories, the challenge is to narrate their experiences and create transparency that enables an audience to grasp the different positionalities (including that of the researcher) as well as the personal relationships that define the encounter. To define one’s place of enunciation (Mignolo 2019), the socio-political position from which filmmakers and research partners express themselves, offers an audience a sense of the diverse epistemologies at play. Ethnographers making themselves accountable for their work by making transparent how they worked is not just to honor an ethical commitment to the people whose worlds they analyze. This also forces them to inquire more rigorously about the kind of knowledge they produce. Luke Lassiter suggested that collaborative ethnography, that is, “the explicit involvement of our research partners in different phases or the whole of the investigative process, not only responds to ethical concerns within the discipline of anthropology”, but more importantly, “it makes our data more succinct, more attuned to how people make sense of the world around them. This is not just a methodological, but a fundamentally epistemological contribution to the ethnographic project as a whole” (Lassiter 2005: 16).

Integrating the research partner into the research process equally requires critical consideration of the researcher for its epistemological contribution to be attuned, not just to the worlds being explored but also to the relationships through which this exploration takes place. However, the need to consider silences and the possibility of falsehoods remains. A collaborative mode of image-making is closer to the lives and visions of the people involved but also invites encounters with the limitations that are suggestive of the holes, gaps, and cracks in the texture of memory-as-narrated. These fragile connections between who we are, how we know, and what we (choose to) remember mean we need to bring the process of knowledge production into critical discussions with our research partners as well as our audiences.

In examining frictions and complications, one does not just observe but experience the boundaries in the field. Proximity and distance to protagonists can be motivated by empathy, affection, and (conflicting) loyalties. Viktor Kossakovsky once said, “Don’t film something you just hate. Don’t film something you just love. Film when you aren’t sure if you hate it or love it. Doubts are crucial for making art”2). I would argue that this also applies to ethnography, where ambiguities or grey zones motivate the journey because they are indicative of the human condition. At the center of these journeys is the capacity to feel oneself into these ambiguities and develop critical empathy through one’s own subjectivity. In this sense, practitioners “do not seek to mitigate the subjective but elevate it as an instrument for the exploration of social worlds” (Laplante, Gandsman and Scobie 2020: 7).

Filmmaking for fieldwork, a form of empirical art, engages with the possibilities and limitations of inter-subjective encounters (Lawrence 2020; MacDougall, 2006, 2019). Over the decades, ethnographic filmmakers have created, shattered, shifted, and expanded paradigms in empirical art. Observational documentaries with long scenes, fewer cuts, hardly any effects, and no music look to remain loyal to the experience mediated through the camera. Interventionist films intend to provoke meaningful reactions involving an overtly present filmmaker as an additional protagonist. Participatory approaches to filmmaking invite protagonists to the image-making process, turning the researcher’s role into that of an observing facilitator. The immersive, sensory modes of filmmaking evoke bodies, affectivities, and atmospheres through extreme closeness to textures and movement. With a camera operating as a fly on a wall, as an involved observer, or as a confident intruder, filmmaking has always been a collaborative art in distilling and abstracting people’s realities. Here, too, truth is important. Situating the filmmaking process at the core of the analysis and making it transparent to the audience is a way of staying true to the experience of the encounter and the relationships the encounter encompassed. To propose a way to go about this, I have identified three analytical dimensions that require consideration: 1) negotiations; 2) impossible engagements (silences, failures, and consequent adaptations); and 3) shared epistemologies (co-creation). Let me elaborate.

1) Negotiations: “Of what use is my story if nobody wants to listen?”

The quote above is from Lucero Cumpa Miranda, an ex-combatant leader of the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA), who is imprisoned in the Chorrillos maximum security facility in Lima3). Her main concern for participating in the film project was to challenge her image as a terrorist leader, reach audiences with her personal story, and explain her choices and regrets. Lucero is one of three research partners and protagonists in the documentary # Between Memories (2015). The 35-minute film is composed of three collaborative short films that are edited so that they enter a conversation “between the memories” of a conflict.

The Peruvian internal armed conflict began in the early 1980s when two guerrilla groups, the Communist Party Shining Path and the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA), declared war against the Peruvian state. Some situate its origins in the ideological fanatism of a few individuals (Portocarrero 2012), while others identify a broader social justice movement mobilized by stark inequalities (Degregori 2003). What followed were 20 years of asymmetric warfare between insurgent groups and the state forces and paramilitary units. Initially, insurgents counted on the wide support of an indigenous peasant population, a politicized youth, as well as artists, scholars, teachers, and their unions. However, increased violence and bloodshed led them to gradually lose this support. The conflict officially ended in 2000 after the disappearance, imprisonment, or retreat of insurgents to inaccessible territories of the country and the collapse of Fujimori’s government, which had been ridden by corruption. According to the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2003, an estimated 70,000 lives were lost, with many more injured and internally displaced people (Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación 2003). Peru entered the 21st century, transitioning from Fujimori’s brutal dictatorship to a fragile democracy.

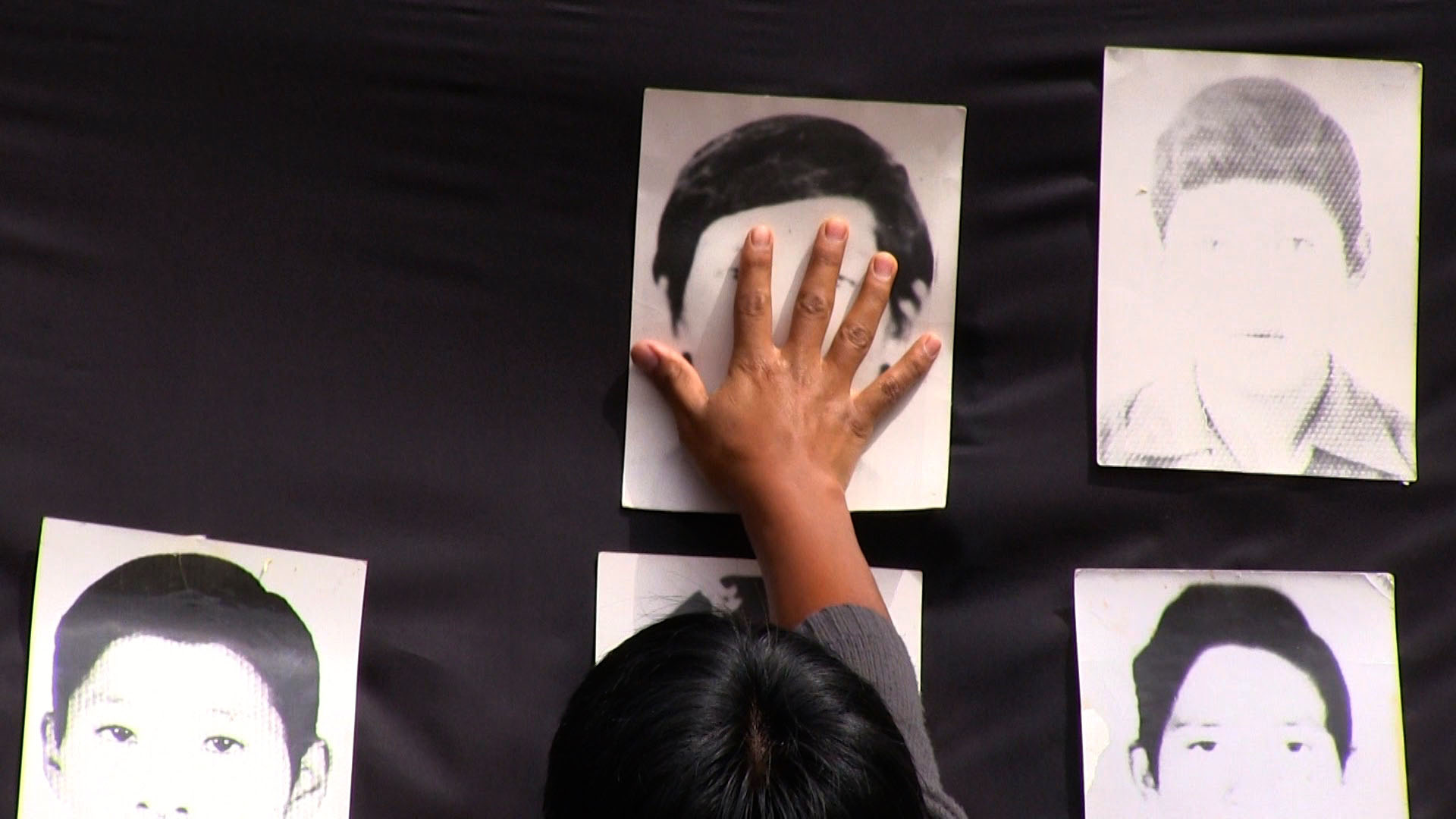

Figure 1 Portraits of disappeared persons during a public vigil in Ayacucho (2012, photo by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich)

Figure 1 Portraits of disappeared persons during a public vigil in Ayacucho (2012, photo by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich)

Lucero was captured by the military in the early 1990s during an insurgent operation. While pregnant, she was tortured, and if she was not to die there, she expected to spend the remainder of her life in prison. Her sentence for high treason was of 25 years. Lucero publicly asked for forgiveness, not for what she believed in or fought against, but for the path she chose to get there4). In the early days of our collaboration, Lucero asked, “Of what use is my story if nobody wants to listen?” She explained that the public wanted to hear the story of a bloodthirsty woman terrorizing the nation for personal gain. If there was no one out there willing to listen to the story that she truly sought to tell, what would be the point?

My intention for this film project was to invite former actors in the conflict to contribute to a dialogue that would allow a more nuanced picture of how this past is remembered. During my fieldwork, I worked with three separate groups. The first group included Lucero and other insurgents in prison with near-life sentences. The second group included former members of the armed forces on trial for crimes against humanity at the time of filming. Finally, the third group included victim-survivors and members of Peru’s largest victims’ organization based in Ayacucho5), the region most affected by the conflict. Working with people from different sides of a conflict, in some cases, former enemies, inevitably exposed the political field in which stories were told and withheld. Public opinion and their gatekeepers, like social media or the boulevard press, create places for memories as well as “placeless” memories (Dietrich 2019: 64). Whoever defines what can or cannot be told circumscribes what society considers threatening or too shameful to narrate. I began by asking my research partners what they thought was important to remember and what stories they would like a public to know.

2) Impossible engagements: (In)visibility and limits of the knowable

Using a camera in the field does not mean that all there is, is what we record. “The camera as a catalyst” means so much more: There are the stories told off-camera. These are the moments of confidentiality enabled by the absence of the red recording light. Speaking to the public through the camera lens can also mobilize a desire to share stories that can only exist in the realms of the private. There are stories that, like puzzles, can only be revealed over time when we have been given enough pieces to make sense of what until then was marginal or confusing. These fragments, the bits and pieces collected on and off camera, are the messy body of the data we create. There is what we see, what we hear, whom we trust, and what we believe (or want to believe); there is reality and fiction, as well as their blurring. This is the stuff that extends beyond the practice of filmmaking and sound recording and describes the difference between documentary filmmaking and research with a camera. The camera as a catalyst in fieldwork situations refers to attentiveness to what the camera’s presence inspires, not solely to what it records. From my experience in postwar settings, a camera is believed to provide public visibility. Being seen and listened to is essential for survivors’ articulations of truth, mourning their dead, celebrating their heroes, and demanding justice from their loved ones. However, when certain truths turn into truths with a capital T, other memories become impossible, unwelcome, and even toxic. With the following example, I want to highlight the pressures and limitations of truth-telling that became evident in the filmmaking process.

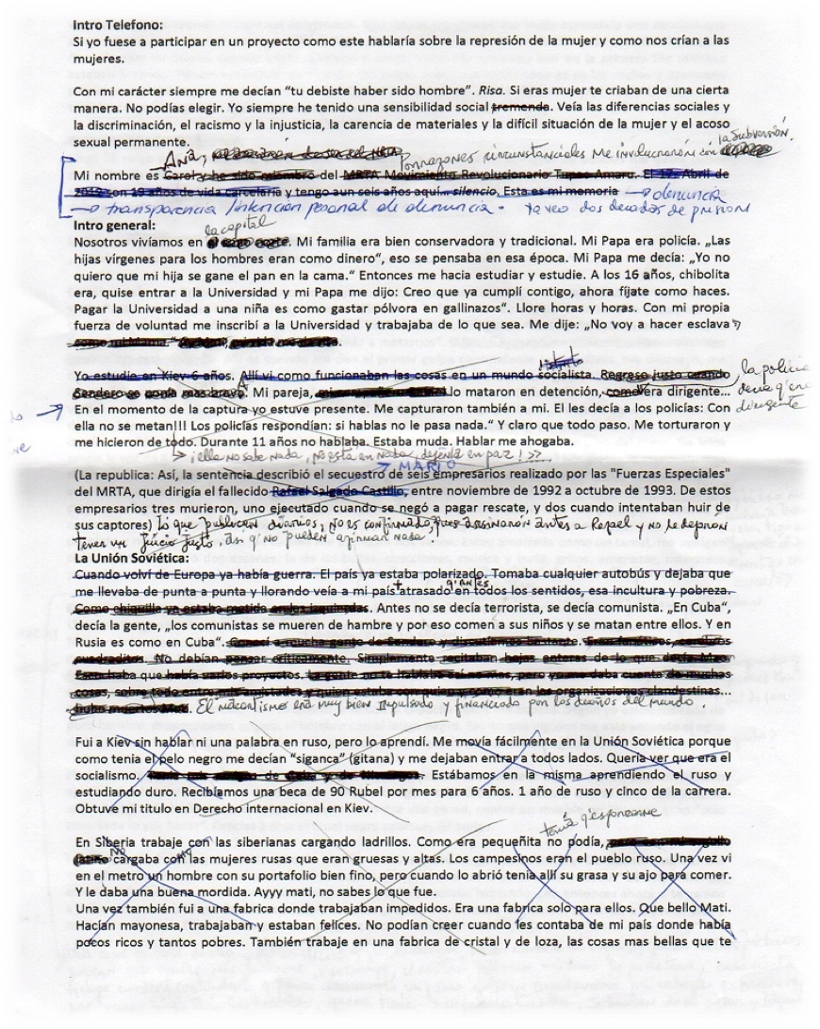

Figure 2 Ana’s edited voice-over text (2014, photo by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich)

Figure 2 Ana’s edited voice-over text (2014, photo by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich)

This is the photograph of a voice-over text from one of my research participants in prison, whose name I have concealed behind the pseudonym “Ana”. After three months of working together on the film, the Interamerican Human Rights Court decided to resume Ana’s case based on new evidence. Like Lucero, Ana was sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment for terrorism and high treason. However, suddenly, there was hope for an early release. In preparation for her court appearance, her lawyers advised Ana that for her case to be successful, she had to become a victim, which meant that the story we had worked on for the film had to change as well: Ana, a young, self-educated woman who joined an insurgent movement out of political awareness and conviction, turned into the naïve (hence innocent) girlfriend of an insurgent leader. In this new version, she was in the wrong place at the wrong time. I knew the story behind the blacked-out bits, and she did not believe in the new version she had written for the film; therefore, we decided to end our collaboration. These conditions would no longer allow it. Commenting on our decision, she said, “in a world in which only the innocent can claim justice, there is no space for ambiguity or political agency, particularly in the case of former female insurgents”.

Our failed collaboration, which she consented to being shared, is suggestive of how stories do not exist in isolation, but extend from and are embedded in an environment of social paradigms and regimes. The anthropologists Michael Jackson writes “stories reconcile fields of experience that are, on the one hand, felt to belong to us, or our own kind and, on the other, felt to be shared or belong to others. Yet, stories may just as trenchantly exaggerate differences, foment discord, and do violence to lived experience’ (Jackson 2006: II). In the process of our partnership, Ana’s story ceased to belong to her and became that of her audience at the Interamerican Human Rights Court. The discourse, whether framed by international law or a Catholic conservative Peruvian public, expected Ana to be a victim. To consider her freedom after more than a decade in prison, Ana needed to comply with the values mobilizing those expectations. Being a female insurgent added another significant layer to the hegemonic discourse that demonized female insurgency to the point of dehumanization. This became explicit in an interview I conducted with one of the leading congresswomen of Peru’s Fuerza Popular Party6):

“The profile of a woman insurgent is Machiavellian. … This evil, this insanity. I believe that it is a privilege to come to this world as a woman. We are privileged because we can give birth to children. It is a divine transformation that God has given us and nobody else. In the depth of their souls, their beings, and their consciousness, they should know that being a woman means protecting life and showing their children to be good men. How is it possible for the soul of a woman to be a terrorist? It does not go to my head … The woman was born to protect against killing. The soul of a woman is always one of reconciliation and tenderness; no? We do not have any other role in the world because this is how we are born” (Interview March 5, 2012, translated by the author).

This added hostility towards female insurgents is rooted in a patriarchal social order but also in a shift from ideologically motivated violence to identity-based violence that changes “the assessment and associations of legitimate violence” (Wilson 2009: 55). Left-wing political agency turned criminal with the effect of privileging some memories over others and shadowing experiences that may diverge from dominating interpretative frameworks. Anna’s untold story indicates that as much as stories are foundational of identity, they are also an expression of what may constitute that identity within a socio-political reality. While the above may refer to stories as told in the language of words, I have also considered these ideas for the language of moving images. If we look at the visibility of stories and how this visibility framed my collaborators’ storytelling, I will now examine what I call audio-visuality, meaning the intricate relationship between form and meaning.

3) Shared epistemologies (co-creation): Collaborative audio-visuality

In the following section, I will elaborate on three examples of audiovisual storytelling choices from the film, “Between Memories” (Dietrich 2018), available in full length at https://boap.uib.no/index.php/jaf/article/view/1559/2620 .

Memory as Process: Observational Filming

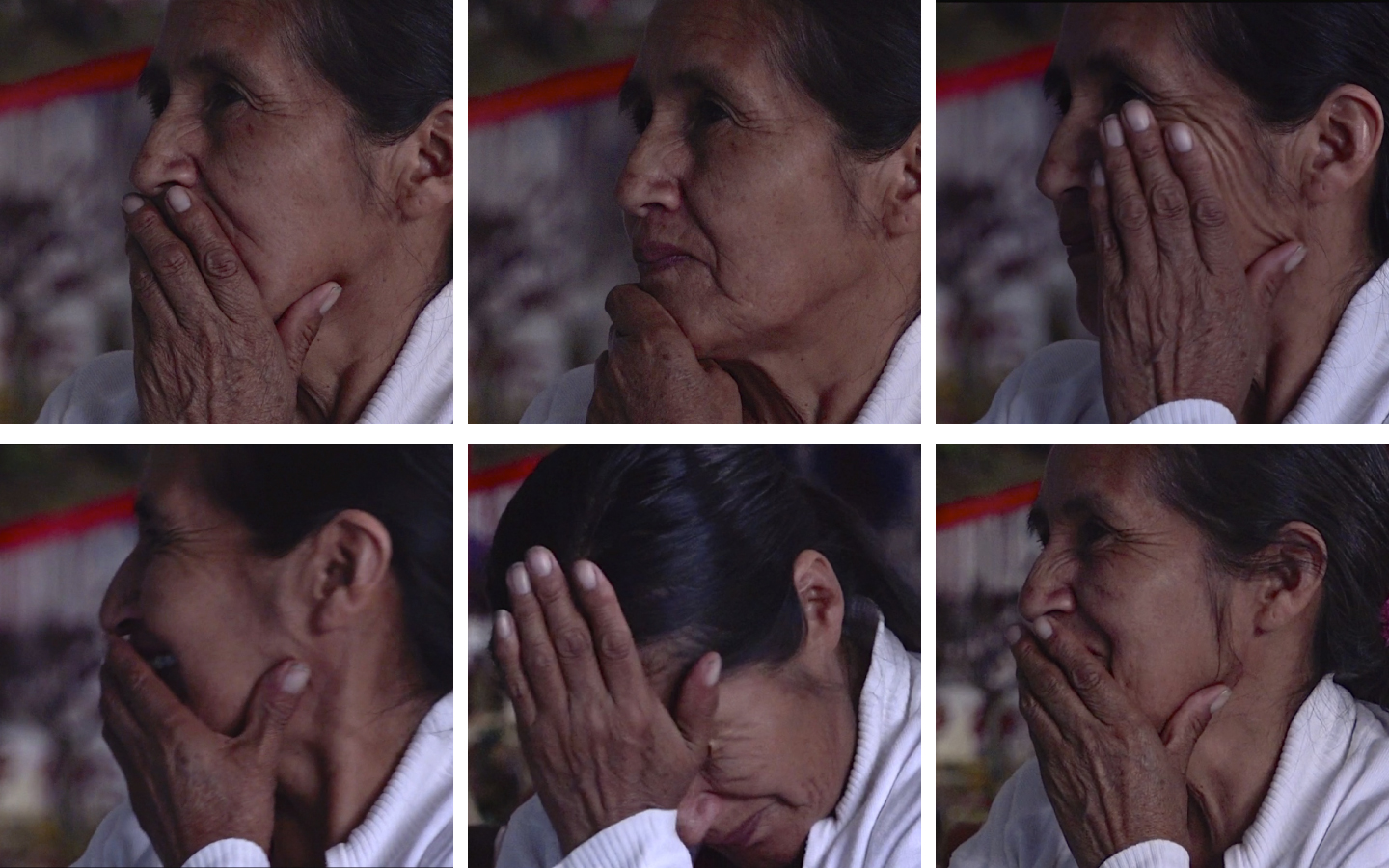

Figure 3 Eudosia Conde Quispe (left) and her mother in Huamanga (2012, photo by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich)

Figure 3 Eudosia Conde Quispe (left) and her mother in Huamanga (2012, photo by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich)

Eudosia, the woman in the picture above, is the wife of Alejandro Segundo Quispe Achas, who disappeared at the hands of paramilitary soldiers in 1984. Being a schoolteacher in their village, they had no fear of the state forces. He used to say, “Why would they (the soldiers) kill me? We have the same employer!” During the cold winter, Eudosia was visiting relatives in another village with her three small children. The couple had arranged to meet there for All Saint’s Day, but he had never turned up. People told her that before his disappearance, members of the Shining Path insurgent group had made a public announcement in their village, to which the teachers were forced to attend. Shortly after, the army appeared, loaded the teachers and other villagers onto a truck, and vanished. “They took them away like animals”, she said. Seven men from Satica7) were taken to Toccto, executed, and dumped in a nearby cave. I was halfway through my fieldwork when Eudosia approached me to ask if I would accompany her with the camera to visit her husband and see the place he now inhabited.

After Eudosia received the terrible news about her husband’s disappearance, she went to look for him. Soon, she found him in that cave but could not take him with her, as she had no means of transporting the heavy body. Days passed until she returned with help, but his remains vanished. Perhaps the dogs, the harsh weather, or the army had “disappeared” him. An exhumation of the mass grave led to the identification of other men from the village but remained inconclusive about her husband’s whereabouts. The uncertainty of his final destination, the haunting memories of a life together, the sense of guilt for leaving his side, and the desperation of perhaps never finding him are what I felt she wanted me to observe with the camera.

Observing the processes motivated by his absence, such as searching for him, praying to find him, and demanding justice, would make the rift that has been torn into their lives painfully tangible. An observational filmmaking approach, inspired by the role of the ethnographer as the observing participant, allowed me to “take particular notice of subtleties of gesture and reaction and how these are embedded in everyday processes” (Lawrence 2020: 20). She went back and forth, not quite knowing where to step and where to place her flowers, which bones to take or where to take them. I understood these observable actions as an expression of her many questions that had no answers.

Eudosia took me under her wings from the day I arrived, but only after knowing her for months did she offer to take me on this journey to Toccto with her. I followed her with my camera affectionately, appreciative of the trust she had in me and determined to convey what she was willing to show me. However, Eudosia had little interest in image-making. Her agency was in the stories she chose to tell and in the places she decided to visit. Recording for a prolonged period, fewer edits, and extended scenes without voice-overs, special effects, or music became techniques for exploring Eudosia’s situated practice of remembering. Observing her with a camera turned into an act of witnessing, whereas the materiality of the recording turned into physical evidence. Both of these actions, which are essential for research in post-war contexts, seemed to be amplified by the camera’s presence. What is performed or “made to be seen” (Banks and Ruby 2011) through the lens is an extension of our agendas and agencies mediated throughout the encounter and, therefore, an expression of our relationship and collaboration.

Figure 4 Eudosia viewing the final film in a private screening (2017, photo by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich)

Figure 4 Eudosia viewing the final film in a private screening (2017, photo by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich)

When Eudosia watched the film for the first time, she was moved by what she saw and was disappointed by what she knew was missing. A series of interviews about her husband’s disappearance with people we met in the hills was not included in the edit. I explained that the story of his disappearance was too complex for an audience to understand in such a short time and needed to be cut. “How am I going to find Segundo if no one knows his story?”, she replied. In the conversation that followed, it became apparent that there were two competing narratives in her film. One focused on telling what had happened to her husband, and the other trying to grasp how she remembered those times. “To me, the former was a question she was still trying to answer, whereas zooming in on Eudosia’s story-telling rendered the epistemologies of violence and its impact on people’s lives tangible”. Her agenda was to find him and mine to understand what she was experiencing. Despite my views on what was “more effective” to convince an audience of the urgency to keep looking for the lost bodies, we agreed on a re-edit in which her interview with a shepherd near the cave would become more central. At the end of our collaboration, she said: “If nothing can be done to find Segundo, our government should learn how missing our loved ones makes us suffer, so they help us build a sanctuary where all the missing can be mourned”. Eudosia’s story speaks of a life fundamentally disrupted by war but also of the possibilities for the state, society and academia to ease the echoes of her pain and that of others.

Memory as Reflection: Essay-Style

Figure 5 Still Image from Between Memories poetically evoking human transience

Figure 5 Still Image from Between Memories poetically evoking human transience (Martha-Cecilia Dietrich 2015, https://boap.uib.no/index.php/jaf/article/view/1559/2620)

At the time of filming, Lucero was still a prisoner at the maximum security facility for women in Lima’s district of Chorrillos. She identified as a prisionera política (political prisoner), implying that the reason for her imprisonment was a matter of conflicting ideologies rather than a specific criminal offense. Others would argue that the term “political prisoner” was misleading since it diminished the gravity of violent crimes committed by insurgents, such as kidnapping public figures in politics and finance or damaging crucial infrastructure. Using the term “political prisoner”, hence respecting their self-identification, I risked suggesting sympathy or even complicity with the MRTA’s choices; so intense was the polarization between the readings.

Many researchers working with former insurgents maintain a low profile because of the strategic practices of terruqueo, which refers to the public slandering of individuals and collectives with the intention to discredit them. Another limitation is access. Requests for access to insurgents in prison were usually denied because they were under a special prison regime. This regime allowed for no cameras, microphones, or interviews without special permits. To avoid the likely rejection, we chose to retain my status as a private visitor and find legitimate ways around the restrictions. This peculiar circumstance enforced a kind of complicity inspired by her incarceration and treatment. The challenge was to find a way to bring Lucero into the film. Lucero suggested to me filming in places of meaning to her, which could be turned into audiovisual metaphors and allegories that would express her memories of her political struggle and incarceration. After reviewing the audio-visual material, she wrote a voice-over text that she read on the phone.

Filming in places of her past and present and collecting images with symbolic connotations gave poetic strength to her piece. The essayistic form of Lucero’s short film involves cinematic techniques that filmmakers often use to express their states of mind. Thoughts lead to the interpretation of an audiovisual world that is pieced together in the edit suite. How the material was brought into its final form arose from Lucero’s memory archive and her aesthetic repertoire (Taylor 2003) in the process of our creative collaboration. Lucero could not record herself but imagined a suitable material that she would pass on as a list or a phone call or tell me about it during my weekly visits. Both subjectivities, hers and mine, became entangled to make her world behind bars accessible to others.

The poetry in Lucero’s interpretative narration of her past, present, and future is both protection from and resistance to the dominant narratives of her story and persona. She chose not to speak of the crimes she committed but of the violent retribution she experienced once in prison: “because this is what people don’t know about me”, she argued. Lucero’s take on a morally damaged world and the political beliefs this world inspired in her were not obscured but made explicit through her poetry. It reminded me of her stories about the early years of imprisonment when authorities had prohibited any form of work or communication. Any sort of personal expression became a form of political resistance, either as paintings and crafts, music, or dance that would carry a symbolic meaning. Until today, it is this certain of meaning that gives her human existence a tangible form. Lucero understood that moving images have similar effects. Feet walking on sand, two pigeons conversing, places and landscapes of personal meaning, and pictures of past as a child and young woman turned into small political acts of resistance. Each image, her voice, and their arrangements express voice, visibility, and defiance.

Memory as Truth: Historical Re-Enactments

Figure 6 Monument to the heroes of Chavín de Huántar (2012, photo by Courtesy Carlos ‘Kike’ Bullón)

Figure 6 Monument to the heroes of Chavín de Huántar (2012, photo by Courtesy Carlos ‘Kike’ Bullón)

Kike Bullón was my main research partner among the military supporters during this conflict. He is an amateur historian and founder of the Civil Association “Friends of the Commandos Chavín de Huántar”8). Kike was the driving force behind organizing the re-enactments of historical battles for the general public. Upon introduction, a common friend invited me to witness the “historical events” at the Replica, the site of Peru’s most famous military intervention against MRTA insurgents. The story told in this building began on December 17, 1996, when 14 MRTA insurgents entered the Japanese ambassador’s residence. The building located in the military barracks in the south of Lima is an exact replica of the residence and was first built for military training purposes and then repurposed as a museum. The government’s ties to the Japanese diplomatic delegation were strong because of then-President Alberto Fujimori’s Japanese descent. Hundreds of diplomats, business executives, government and military officials had been invited to celebrate the Japanese emperor’s 63rd birthday when the insurgents took around eight hundred guests and personnel hostage.

Despite releasing most hostages that night, they retained 72 high-ranking government and military officials for more than four months. The MRTA insurgents led by Néstor Cerpa Cartolini sought to negotiate the liberation of 450 comrades from prison and spur a revision of Fujimori’s neoliberal market reform. Fujimori’s government signaled the keenness to find a peaceful solution while secretly preparing for a major military intervention that was rehearsed at the Replica. The embassy hostage crisis ended when 140 commandos of the Peruvian anti-terrorist unit for special operations—Chavín de Huántar—freed the hostages by storming the house9). One hostage, two commandos, and all 14 insurgents were killed in this operation.

Despite the controversy surrounding the alleged extrajudicial killings of the insurgents, army veterans celebrate this military intervention as the most memorable victory of state forces against insurgency. The mediatization of the operation and the films and TV series that followed transformed the soldiers of the special commando and the hostages into heroes. Thirteen years later, in 2009, during a series of court cases against military personnel for crimes against humanity, Kike and his peers felt that heroism by the armed forces began to crumble. “It was time to refresh peoples’ memories”, Kike explained in an interview in March 2012. “This”, he continued, “was the beginning of the public re-enactments, so people would know, live and feel what our soldiers did to safe our nation and our democracy”.

When I asked Kike what film he would like to make as part of this project, he suggested that any contribution was meant to “set the record straight” because human rights groups had hijacked the truth about the commandos and dragged their honor through the mud. We agreed to record the re-enactments as “historical events”, meaning that we would record the performance as it was played out. Kike also arranged for me to interview Pepe Garrido, a former commander of the armed forces who was one of the 72 hostages. Kike did not want to conduct the interview himself but instead pulled the strings behind the scenes. The interview was essential to him because it would offer some context for the re-enactments. He felt that General Garrido could provide both the experiences of a hostage and a soldier.

At the time of the interview, Pepe Garrido was on trial for human rights violations that had occurred during his service as a commander in the Department of Ica. Before recording, he announced that he did not want to speak about politics or his trials. He was coming to give an account of what happened to the soldiers on the battlefield and during the hostage crisis, which I would cut together with the material of the re-enactments. Mr. Garrido talked passionately about the fears of a soldier in combat, the terrifying experience of asymmetric warfare, and not knowing an enemy that hid among civilians. I did not ask a single question. He came “to speak the truth and to defend what’s right” and “if this (film) was going to be seen by human rights advocates, they should consider what he had to say”. Truth-telling here only works if understood literally. His expressions attempted to congeal his narrative through repetition and assertion, but as such, they also spoke of corrosion. Much is at stake for Kike, Pepe, and other associates of state forces. After our first recording session, Kike told me that this was not a memory but a history-making exercise. When lives are built on historical certainties, the battle over memory, so I found, is not just ideological but existential because these lives can only continue to be lived (in this way) if their narratives retain the status of official history.

After Description and Analysis

Once the three short films were completed, I began to show them individually in Lima and Ayacucho. I realized that I was showing them to audiences sympathetic to the respective narratives confirming each audience’s version of the past. The films circulating in this form turned out to be serving a polarized discourse rather than complicating it. When I asked my protagonists if they would give me permission to cut my own version of the film, I did not ask to change their films but to incorporate them into one larger film held together by my reflections on the story-telling process. The thread through this film was my voice-over narration, which describes our encounters and the subsequent journey of putting the stories together. The more I brought myself into the film, the greater I felt the need to incorporate myself into the story through scenes of interaction, asking questions, and describing my personal motivations for making this film.

Why did I care about putting the three films into conversation with each other? What inspired the creation of dialogue “between memories” that seemed to barely exist in reality? I found answers in conversations with my mother. Before the conflict, she was a sociology student at the National University of San Marcos and a passionate left-winger, while many of her close families supported Fujimori’s regime. My family was subject to deep ideological conflicts, and I only noticed how much this had affected my personal relationships with my research partners at the end of the filmmaking process. Working out my personal entanglements with the material culminated in writing my own voice-over that reflected the journey through the experience of memory-mine and that of my research partners in post-conflict Peru.

This was the day of the film’s premiere. Eudosia and the “mothers” of ANFASEP, Lucero’s two children, Iris and Ernesto, Kike, his family, and my family, had come to the first public screening at the National Museum of Memory (LUM) in early 2016. With the audience in between, the main protagonists spoke of their experiences during the conflict. It is difficult to determine whether everyone listened. The conversation was fragmented, and many comments were isolated from each other, reminding me of the three separate stories in the film that emulated the memory discourse in Peru: disjointed and remote.

Figure 7 Peru Premiere of Between Memories at the LUM in 2015 (Photo by Jose Luis Fajardo)

Figure 7 Peru Premiere of Between Memories at the LUM in 2015 (Photo by Jose Luis Fajardo)

During the Q&A, the discussion about the filmmaking process and the limitations of my collaborations offered the glue that held the stories together, just like in the film, but this time, there was space for the stories of the audience. Then, something unexpected happened. Lucero’s daughter, Iris, read a letter from prison. After some murmur in the hall, Iris began to read. Lucero’s words could be heard through the gentle voice of her daughter. More than two decades earlier, Lucero gave birth to her amid the horror of torture and clandestine imprisonment. She lived with her mother in prison until she was three years old. After her third birthday, she was handed over to Lucero’s relatives, and a life of loneliness and longing between prison visits began. Nevertheless, she was reading her mother’s words of apology to an audience of victims, perpetrators, and a new generation. In my video recording of the Q&A, I see people clapping who would have never clapped to an insurgent’s words. It happened here. This was the moment after description and analysis, when the reflective process became also productive for my research. The conversations inspired by the film allowed the audience to negotiate what they knew and positioned themselves accordingly. By producing and circulating singular memories of the conflict, I perpetuated the violence of a polarized discourse, but by entangling these memory stories in the edit suite, a space opened up in which the contentiousness, the incommensurability of accounts, and the different experiences entered a conversation made of contrasting reflections. The collective viewing experience altered our conversation from creation-as-process to reflection-as-process, evoking an understanding of truth-telling as memory-making practice. There are memories that focus on the past and those that look towards the future (Akama, Pink and Sumartojo 2018). The uncertainty of how the past may catch up with the present causes a sense of being “stuck” in the past, which was a tangible force during the co-creative process. The screening gave a glimpse into a future that was no longer in the hands of those who experienced and fought the war but those who had arisen from it.

In the Spirit of Closure

Collaborative co-creative storytelling is a socially situated, contextual, historical, and personal methodology that can expand its epistemological meaning for research when the creative practice is ethically attuned to the life worlds it seeks to explore. We construct this world through norms and boundaries as well as through their transgressions (Lawrence 2020). Only by learning how we know can we begin to understand what we know.

Filmmaking is a process that is deeply entangled with social worlds shared with others (Grimshaw and Ravetz 2005, 2009; Banks and Ruby 2011). In this sense, camera-led research collaborations work with the experiences of both filmmakers and the filmed. In this project on the experience of memory in post-conflict Peru, the presence of the camera—and not solely its recordings—sought to make the forces that define people’s lifeworlds tangible. By making explicit what can and cannot be made visible in filming and in writing, we can obtain a sense of the dynamics that generate dominant narratives, margins, and silences. For this to work, the method of co-creation also requires an analysis of the research encounter, which encompasses personal histories and engagements, agencies, and agendas of all research partners involved. Audiences must understand what drives and motivates people to create their relationships and contexts.

Through the making of the film “Between Memories” (2015), I have found that engaged practice and creative expression articulate two key aspects of memory: its visibility and visuality. Whereas visibility constitutes the social and political framing of audiovisual storytelling, audio-visuality refers to the relationship between aesthetic form and its specific social meanings. The camera, as a catalyst of social relationships, amplifies and expresses the politics and poetics of remembering the conflict. What people choose to narrate, how and where may give answers as to why narrating these specific stories is significant to them. In this sense, storytelling as research intervention elicits the grey zones between memories that can or cannot be narrated, whereby the “if” also determines the “how”. The stylistic vehicles through which my research partners choose to tell their stories (observationally, poetically, and historically) are suggestive of the epistemologies of remembering violent conflict—how people build unsettling experiences into their contemporary lives. My research partner’s need to assert or disrupt narratives does not solely relate to their past experiences but to how they live their lives in the present. If we know how people choose (or see themselves forced) to remember the past, the insight we obtain is less concerned with the truth of what happened but rather with the strategies that create a sense of belonging, frameworks of thought, and (political) agencies.

Notes

- 1)

- This article uses non-specific gender pronouns (they/them) regardless of whether the gender is unspecified or open to the appropriation of a diverse readership.

- 2)

- Kossakovsky explains it as rule #4 in his ten rules of documentary filmmaking (https://www.desktopdocumentaries.com/Documentary-Director-Viktor-Kossakovskys-10-Rules-of-Filmmaking.html,accessed November 3, 2021).

- 3)

- Lucero was released from prison in October 2020.

- 4)

- See, for instance, https://kaosenlared.net/lucero-cumpa-simbolo-de-la-resistencia-de-la-mujer-peruana/ (accessed November 3, 2021)

- 5)

- ANFASEP, Asociación Nacional de Familiares de Secuestrados, Detenidos y Desaparecido del Perú. https://anfasep.org.pe/ (accessed November 3, 2021)

- 6)

- Fuerza Popular is a political party that continues the legacy of former president Alberto Fujimori. Their political style is also known as Fujimorismo. Fujimori’s daughter, Keiko, assumed the party’s leadership since her father was imprisoned for crimes against humanity during the conflict. https://fuerzapopular.com.pe/ (accessed May 30, 2022)

- 7)

- In the principality of Ayacucho (district of Los Morochucos, Cangallo province)

- 8)

- Asociación Civil Amigos de los Comandos Chavín de Huántar

- 9)

- This video shows the events of the liberation as covered by the media: http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=0kdjmZMmCSg (accessed May 30, 2022)

References

- Akama, Y., S. Pink, and S. Sumartojo

- 2018

- Uncertainty & Possibility: New Approaches to Future Making in Design Anthropology. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Alexandra, D.

- 2019

- More Than Words: Co-Creative Visual Ethnography. In: M. Nuñez-Janes, A. Thornburg. and A. Booker (eds.) Deep Stories. Practicing, Teaching, and Learning Anthropology with Digital Storytelling. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

- Antze, P. and M. Lambek (eds.)

- 1996

- Tense Past: Cultural Essays in Trauma and Memory. London: Routledge.

- Arendt, H.

- 1958

- The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press.

- Banks, M. and J. Ruby (eds.)

- 2011

- Made to Be Seen. Perspectives on the History of Visual Anthropology. University of Chicago Press.

- Clarke Kamari, M. and M. Goodale (eds.)

- 2010

- Mirrors of Justice: Law and Power in the Post-Cold War Era. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación (CVR)

- 2003

- Informe final de la comisión de la verdad y reconciliación. Tomo I-VIII, Lima: CVR.

- Degregori, C. I.

- 2003

- Jamás tan cerca arremetió lo lejos. Memoria y violencia política en el Perú. Lima: IEP/SSRC.

- Dietrich, M. C.

- 2018

- Between Memories. A Collaborative Journey into the Experience of Memory in Post-War Peru. Journal of Anthropological Films 2 (2): e1559.

- 2019

- Pursuing the Perpetual Conflict: Ethnographic Reflections on the Persistent Role of the “Terrorist Threat” in Contemporary Peru. History and Memory 31(1): 59–86.

- Eltringham, N.

- 2021

- The Anthropology of Peace and Reconciliation-Pax Humana (Critical Topics in Contemporary Anthropology). London: Routledge.

- Grimshaw, A. and A. Ravetz

- 2005

- Visualizing Anthropology. Bristol: Intellect.

- 2009

- Observational Cinema. Anthropology, Film, and the Exploration of Social Life. Indiana University Press.

- Henley, P.

- 2010

- The Adventure of the Real. Jean Rouch and the Craft of Ethnographic Cinema. The University of Chicago Press.

- Jackson, M.

- 2006

- The Politics of Storytelling. Variations on a Theme by Hannah Arendt. University of Chicago Press.

- Kesselring, R.

- 2017

- How Can We Write about the Experience of Violence? Combined Academic Publishers Blog.

- Kwon, H.

- 2006

- After the Massacre: Commemoration and Consolation in Ha My and My Lai. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Laplante, J., A. Gandsman, and W. Scobie (eds.)

- 2020

- Search after Method. Sensing, Moving, and Imagining in Anthropological Fieldwork. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Lassiter, E. L.

- 2005

- The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography. University of Chicago Press.

- Lawrence, A.

- 2020

- Filmmaking for Fieldwork: A Practical Handbook. Manchester University Press.

- MacDougall, D.

- 2006

- The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography, and the Senses. Princeton University Press.

- 2019

- The Looking Machine: Essays on Cinema, Anthropology and Documentary Filmmaking. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Mignolo, W. D.

- 2019

- The Enduring Enchantment (Or the Epistemic Privilege of Modernity and Where To Go from Here). London: Routledge.

- Milton, C. (ed.)

- 2014

- Art from a Fractured Past: Memory and Truth-Telling in Post-Shining Path Peru. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Portocarrero, G.

- 2012

- Profetas del Odio. Raíces culturales y líderes de Sendero Luminoso. Lima: Fondo editorial PUCP.

- Radstone, S. and B. Schwarz (eds.)

- 2010

- Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates. Fordham University Press.

- Rouch, J.

- 2003

- Ciné-Ethnography. University of Minnesota Press.

- Suhr, C. and R. Willerslev (eds.)

- 2013

- Transcultural Montage. New York and Oxford: Berghahn.

- Taylor, D.

- 2003

- The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Wilson, F.

- 2009

- Violence, Identity and (In)security: Experiencing the Maoist Insurgency in Peru. IDS Bulletin 40(2): 54–61.

Films

- Dietrich, M.C.

- 2015

- Between Memories. The Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology. Distributed by the Royal Anthropological Institute, Peru and UK, 34:25.

https://boap.uib.no/index.php/jaf/article/view/1559/2620 (Retrieved January 1, 2023) - 2022a

- Eudosia visiting her husband’s grave. Produced by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich, Amsterdam, 3:48.

https://vimeo.com/774900535 (Retrieved January 1, 2023) - 2022b

- A phone call from prison. Produced by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich, Amsterdam, 2:23.

https://vimeo.com/774900669 (Retrieved January 1, 2023) - 2022c

- Re-Enactment of the retaking of the Japanese ambassador’s residence by the comandos Chavin de Huantar.

Produced by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich, Amsterdam, 6:21.

https://vimeo.com/774900782 (Retrieved January 1, 2023) - 2022d

- Tablas de Sarhua narrating the internal armed conflict are juxtaposed with the author’s personal voice-over.

Produced by Martha-Cecilia Dietrich, Amsterdam, 2:12.

https://vimeo.com/774900895 (Retrieved January 1, 2023)